Airfleck - Airfleck

More Posts from Airfleck and Others

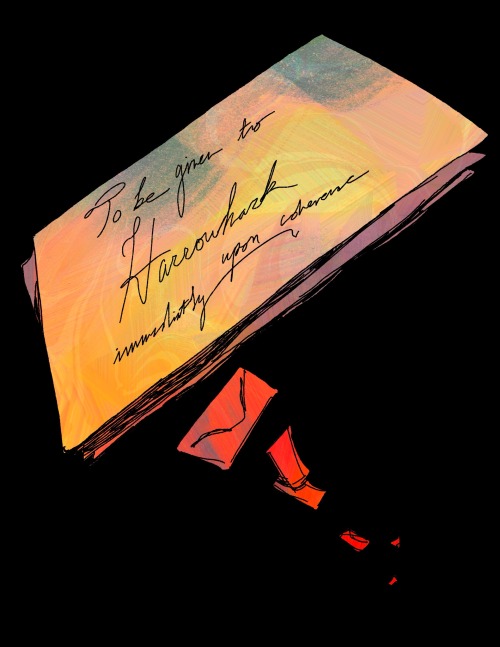

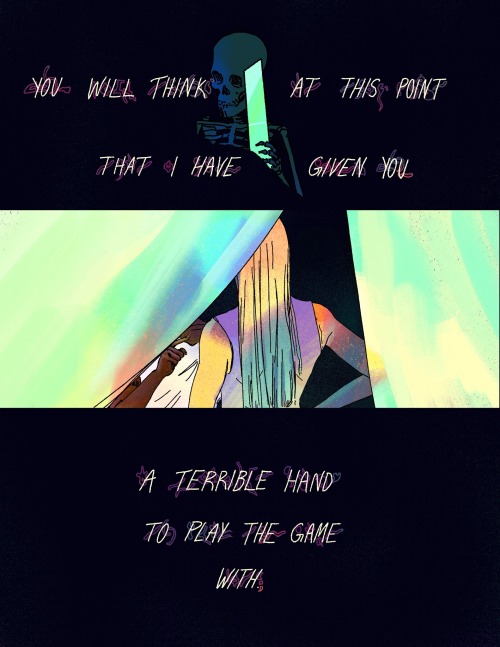

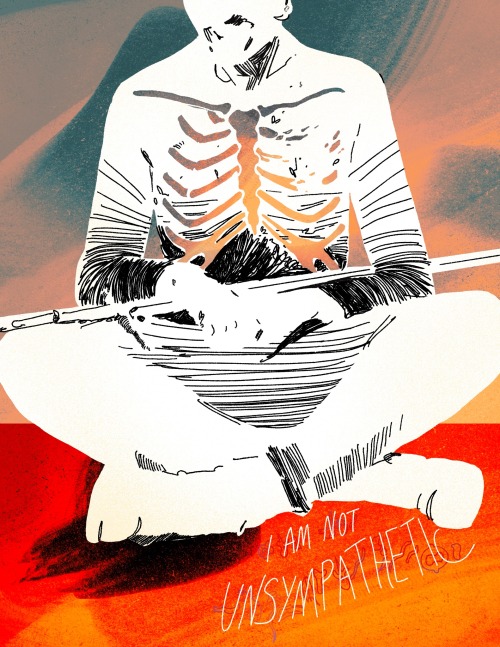

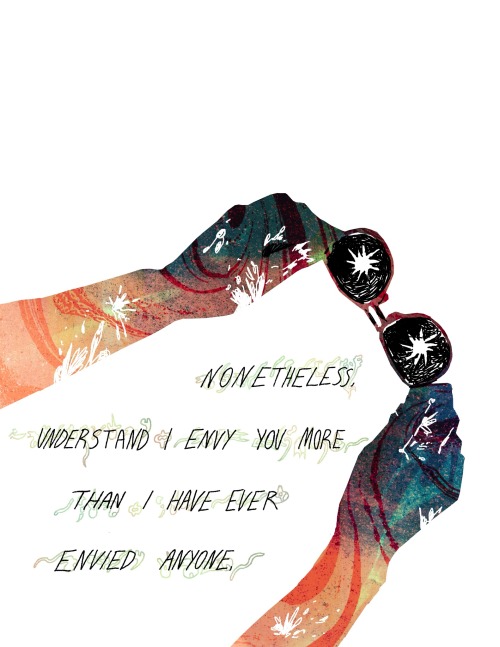

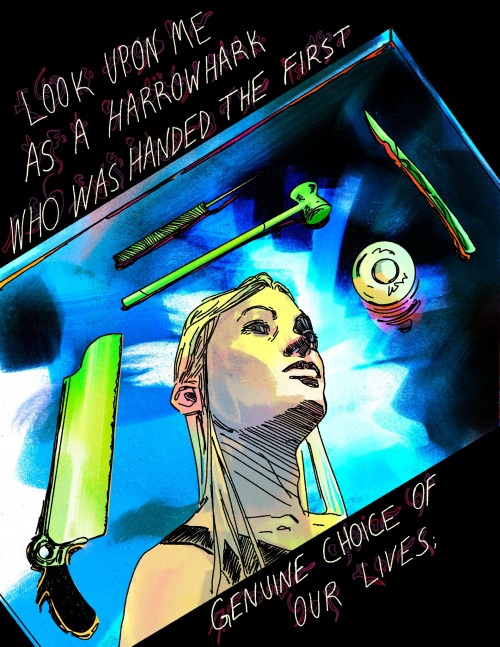

what if the vengeful soul of the earth remembered the people who cared about her and braided her hair every morning. what then

(bonus because I know this is what you guys wanted and I'd hate to disappoint)

I like how Jonathan freely admits how scared he is or how he could be easily crushed by the other man or how he never states that he must stay the course because he's not a coward etc

And then all "academic analyses" of the text say he's hypermasculine as if Dracula didn't just pull a "make sure to break your hand-shaking partner's fingers to assert dominance".

Impending rant aside, Jonathan is a perfect example of fear meaning bravery. Unlike other protagonists of his time, he doesn't scoff and turn his nose up at the danger he's in. He's not a prideful Englishman self-assured of his main character status giving him plot armour. He doesn't callously dismiss the warnings or try to assert his British-ness over the Count.

He's humble and not afraid to tell his fiancée how unnerved he is by how much stronger the Count is than him. He can't even hide his distress from the Count out of politeness– he's very expressive: a contradiction to the British stereotype of an unmoved prig with a stiff upper lip. He also just doesn't get defensive about his bravery. He's not worried about being seen as a coward, and that is precisely what prevents him from being one. He goes forth with his work not to prove himself a man but to prove himself a dependable employee. And to get that bread.

Like, I can't help but compare him to Hippy Rowan from A Kiss of Judas. Hippy attacks a man who was merely minding his business out of irrational fear but presents his fear as disgust instead, and later on, he brags about never having ever felt terror, to which the men he is staying with respond with a bet that they can show him true terror beyond his imagination. They were just planning to put on masks and jumpscare him when he was not expecting, but just the anticipation of being proven a coward leaves him bedridden with dread. Now that is stupidity and cowardice.

Jonathan's a brave man. He's not stupid, he's not arrogant, he is aware of his helplessness but still determined to pull through for the sake of his loved ones.

What do you think of Docholligay’s take on Ruka, that being that he’s a projection of Juri’s dark side and that, in shattering the locket, she overcomes?

Man, it is a good-ass take that I love a lot.

It really fixes the one big issue with the otherwise amazing two-parter of episodes 28 and 29 wrapping up Juri’s issues. Which is of interloper Ruka. Personal feelings about Ruka as a character aside (which is really kind of tied up in the ‘men of Utena’ as a whole, that he seemingly gets to waltz in, fuck shit up, and leave with relatively little consequence to himself), it is profoundly weird that this issue of Juri and Shiori’s relationship is only ‘solved’ when this random guy who we have never heard of before and never will again shows up. But that ends up only SUPPORTING Doc’s read.

I had previously read the whole thing of Ruka not being spoken of before and after his time to be more of a function of the insular space-time weirdness of Ohtori where anything that isn’t there might as well not exist to those within it. But that’s just the thing - space and time does weird things in Ohtori and that manifests in odd ways - SEE MIKAGE. Which only grows more relevant as both Mikage’s final episodes and Ruka’s episodes are some of the most blatant foreshadowing of the ending of the show (where Utena ‘leaves’ the school and Anthy frees herself). If Mikage is a ghost, then why isn’t Ruka as well?

I don’t think that Juri necessarily invented Ruka wholecloth. With Doc’s reading in mind I do read him as a combination of Juri’s dark side manifest AND a ghost (that at some point in Juri’s past there was a ‘Ruka’ who mentored her but he’s long dead, hence why everyone else is so confused when the ‘old’ fencing captain shows up). Much like most of the cast, Juri has trapped herself in a toxic pattern regarding her inability to move on from her feelings for Shiori and imagine a happy future for herself (something she thinks would take ‘a miracle’ so mired she is in self-loathing). We see her try to break the cycle before and fail miserably - in episode 17 she throws away the locket, a good and healthy thing, but the moment it reappears in front of her she cannot reject it again. Juri must be aware on a subconscious level that she needs SOMETHING to break through this, but she isn’t prepared to do it on a conscious level - she is tied up in the idea that she can only be happy if Shiori returns her feelings, so to reject Shiori would to be giving up any hope, thus she chases her tail over and over for ‘a miracle’. So the idea of an influential man in her life (and that it is a MAN who is able to, briefly, have a ‘normal’ heterosexual relationship with Shiori is a big part of that) becoming the avatar of all the things she feels she can’t surpass or are holding her back - that sounds like just the kind of thing that can manifest as a ghost in Ohtori’s weird space-time-ness.

Which really only makes the foreshadowing of the end of the series only more potent. I used to bristle at this idea of Ruka being ‘a prince who saved Juri because of his man-love bleh’ since he ‘dies’ after Juri is freed, comparable to the young man in her story about her sister nearly drowning (and comparable to Utena disappearing after opening the coffin). BUT this changes it significantly - much like how Anthy cannot be pulled out of the coffin and must choose to reach back to Utena, Juri ultimately frees herself. Ruka is her manifestation and he ‘dies’ like a prince because ‘princes’ are fuck-all useless - at the end of the day the true ideal of ‘the prince’ never existed, and pursuing that ideal only leads to failure. We are supposed to read Akio and Dios as denigrating Utena in the final episodes when they say she’s ‘just a girl’ - but a nonexistent prince can’t help anyone. Only by reaching out to Anthy as a human being, as a GIRL, can Utena help break this cycle of abuse and loathing that Anthy has mired herself in. By giving herself someone to struggle against, Juri can throw away the rose and forfeit the duel, finally abandoning the endless and futile search for ‘a miracle.’ So really when you read Ruka not as an actual dude who suddenly dies after inserting himself into the drama of these two girls, but as the ghost-simulacrum of who Juri both wants and fears to become, Ruka suddenly makes much more sense in regards to not only Juri’s arc but to the overall themes of RGU.

-

kryptickurrency liked this · 1 month ago

kryptickurrency liked this · 1 month ago -

lemonpilotingmech liked this · 1 month ago

lemonpilotingmech liked this · 1 month ago -

iceagegems liked this · 1 month ago

iceagegems liked this · 1 month ago -

eddiehaley liked this · 1 month ago

eddiehaley liked this · 1 month ago -

jarvilehtos reblogged this · 1 month ago

jarvilehtos reblogged this · 1 month ago -

marble-reblogs reblogged this · 1 month ago

marble-reblogs reblogged this · 1 month ago -

stargazing-enby reblogged this · 1 month ago

stargazing-enby reblogged this · 1 month ago -

stargazing-enby liked this · 1 month ago

stargazing-enby liked this · 1 month ago -

ender--gaming reblogged this · 1 month ago

ender--gaming reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ambroseandmox reblogged this · 1 month ago

ambroseandmox reblogged this · 1 month ago -

steinbit liked this · 1 month ago

steinbit liked this · 1 month ago -

sjura reblogged this · 1 month ago

sjura reblogged this · 1 month ago -

petiolata reblogged this · 1 month ago

petiolata reblogged this · 1 month ago -

saisaixchan liked this · 1 month ago

saisaixchan liked this · 1 month ago -

luno143 liked this · 1 month ago

luno143 liked this · 1 month ago -

burguerwithoutsalad reblogged this · 1 month ago

burguerwithoutsalad reblogged this · 1 month ago -

burguerwithoutsalad liked this · 1 month ago

burguerwithoutsalad liked this · 1 month ago -

ptompetompetomalleyways liked this · 1 month ago

ptompetompetomalleyways liked this · 1 month ago -

littletinydoom liked this · 2 months ago

littletinydoom liked this · 2 months ago -

themediocreprince liked this · 2 months ago

themediocreprince liked this · 2 months ago -

your-local-depressed-fangirl liked this · 2 months ago

your-local-depressed-fangirl liked this · 2 months ago -

pipsqueak317 liked this · 2 months ago

pipsqueak317 liked this · 2 months ago -

stargazin-on-mars reblogged this · 2 months ago

stargazin-on-mars reblogged this · 2 months ago -

stargazin-on-mars liked this · 2 months ago

stargazin-on-mars liked this · 2 months ago -

neverfeartheboysarehere reblogged this · 2 months ago

neverfeartheboysarehere reblogged this · 2 months ago -

neverfeartheboysarehere liked this · 2 months ago

neverfeartheboysarehere liked this · 2 months ago -

rainebownerd reblogged this · 2 months ago

rainebownerd reblogged this · 2 months ago -

rainebownerd liked this · 2 months ago

rainebownerd liked this · 2 months ago -

smoooothbrain reblogged this · 2 months ago

smoooothbrain reblogged this · 2 months ago -

smoooothbrain liked this · 2 months ago

smoooothbrain liked this · 2 months ago -

postluminescence reblogged this · 2 months ago

postluminescence reblogged this · 2 months ago -

postluminescence liked this · 2 months ago

postluminescence liked this · 2 months ago -

goodvibes-42 liked this · 2 months ago

goodvibes-42 liked this · 2 months ago -

loveofmyknife liked this · 2 months ago

loveofmyknife liked this · 2 months ago -

iwillstabyou liked this · 2 months ago

iwillstabyou liked this · 2 months ago -

evenchance liked this · 2 months ago

evenchance liked this · 2 months ago -

hashbrownsoncrack liked this · 2 months ago

hashbrownsoncrack liked this · 2 months ago -

queer-whatchamacallit liked this · 2 months ago

queer-whatchamacallit liked this · 2 months ago -

under-a-shady-ash-tree liked this · 2 months ago

under-a-shady-ash-tree liked this · 2 months ago -

autism-sprinkles liked this · 2 months ago

autism-sprinkles liked this · 2 months ago -

ode-to-berlermo reblogged this · 2 months ago

ode-to-berlermo reblogged this · 2 months ago -

ode-to-berlermo liked this · 2 months ago

ode-to-berlermo liked this · 2 months ago -

burana006 reblogged this · 2 months ago

burana006 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

idk-what-im-doing-ahhhhhh liked this · 2 months ago

idk-what-im-doing-ahhhhhh liked this · 2 months ago -

hazel-almira liked this · 2 months ago

hazel-almira liked this · 2 months ago -

wormmutt liked this · 2 months ago

wormmutt liked this · 2 months ago -

emotional-support-werewolf liked this · 2 months ago

emotional-support-werewolf liked this · 2 months ago -

verymentalityangel liked this · 2 months ago

verymentalityangel liked this · 2 months ago