Echozeta - Untitled

More Posts from Echozeta and Others

What exactly is a sun eclipse? Will I be able to see it and if so when from the Netherlands?

The solar eclipse is when the moon is directly in front of the Sun and creates a shadow on the Earth. They happen about once every 18 months. I don’t believe that you’ll be able to see this eclipse from the Netherlands. I think the next one to be in Europe is in 2026. There’s one in Chillie and Argentia in 2019 and another in Antartica in 2021.

There’s a push to crowdfund an Ida B. Wells monument in Chicago. They’re around halfway there. Let’s give them a boost.

2017 Was One of Our Planet’s Hottest Years on Record

We just finished the second hottest year on Earth since global temperature estimates first became feasible in 1880. Although 2016 still holds the record for the warmest year, 2017 came in a close second, with average temperatures 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the mean.

2017’s temperature record is especially noteworthy, because we didn’t have an El Niño this year. Often, the two go hand-in-hand.

El Niño is a climate phenomenon that causes warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean waters, which affect wind and weather patterns around the world, usually resulting in warmer temperatures globally. 2017 was the warmest year on record without an El Niño.

We collect the temperature data from 6,300 weather stations and ship- and buoy-based observations around the world, and then analyze it on a monthly and yearly basis. Researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) do a similar analysis; we’ve been working together on temperature analyses for more than 30 years. Their analysis of this year’s temperature data tracks closely with ours.

The 2017 temperature record is an average from around the globe, so different places on Earth experienced different amounts of warming. NOAA found that the United States, for instance, had its third hottest year on record, and many places still experienced cold winter weather.

Other parts of the world experienced abnormally high temperatures throughout the year. Earth’s Arctic regions are warming at roughly twice the rate of the rest of the planet, which brings consequences like melting polar ice and rising sea levels.

Increasing global temperatures are the result of human activity, specifically the release of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane. The gases trap heat inside the atmosphere, raising temperatures around the globe.

We combine data from our fleet of spacecraft with measurements taken on the ground and in the air to continue to understand how our climate is changing. We share this important data with partners and institutions across the U.S. and around the world to prepare and protect our home planet.

Earth’s long-term warming trend can be seen in this visualization of NASA’s global temperature record, which shows how the planet’s temperatures are changing over time, compared to a baseline average from 1951 to 1980.

Learn more about the 2017 Global Temperature Report HERE.

Discover the ways that we are constantly monitoring our home planet HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Land is Sliding, Tell Us Where!

Summer in the northern hemisphere brings monsoon season, causing heavy rains and flooding that trigger landslides. Next time you see a landslide in the news, online, or in your neighborhood, submit it to our citizen science project Landslide Reporter to build the largest open global landslide catalog and help us and the public learn more about when and where they occur.

Rainfall is the most common cause of landslides.

After a storm, the soil and rock on a slope can become saturated with water and begin to slide downwards, posing a danger to people and destroying roads, houses and access to electricity and water supplies.

We have been monitoring rainfall from space for decades.

Orbiting the Earth right now, the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission is a group of 10 satellites that measure rain, snow, sleet and other precipitation worldwide every three hours. This data tells us where and when heavy rain is falling and if it could lead to disasters.

What can rainfall data tell us about landslides?

We’re using GPM data to understand where and when landslides are happening. A global landslide model uses information about the environment and rainfall to anticipate where landslides are likely to happen anytime around the world every three hours.

To improve the global landslide model and other landslide research, NASA is looking for citizen scientists like you!

If you find a landslide reported online or in your neighborhood, you can provide the event details in Landslide Reporter, our citizen science project.

Your detailed reports are added into an open global landslide inventory available at Landslide Viewer. We use citizen science contributions along with other landslide data to check our prediction model so we can have a better picture of how rainfall, slope steepness, forest cover, and geology can trigger a landslide.

Because the data is open, anyone can use the data for research or response.

When you report a landslide, you improve our collection of landslide data for everyone.

Help support landslide efforts worldwide by contributing to Landslide Reporter, and you can help inform decisions that could save lives and property today! Learn more about the project at https://landslides.nasa.gov. You can also follow the project on Twitter and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Tools of the Trade: How Parker Solar Probe Will Study the Sun

Our Parker Solar Probe will get closer to the Sun than any spacecraft has ever gone – it will fly right through the Sun’s corona, part of the Sun’s atmosphere.

This spacecraft is full of cutting-edge technology, from its heat shield down to its guidance and control systems. It also carries four suites of advanced instruments designed to study the Sun in a multitude of ways.

1. Measuring particles

Two of Parker Solar Probe’s instrument suites are focused on measuring particles – electrons and ions – within the corona.

One of these particle-measuring instrument suites is SWEAP (Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons). SWEAP counts the most common particles in the solar wind – the Sun’s constant outflow of material – and measures their properties, like velocity, density and temperature. Gathering this information about solar wind particles will help scientists better understand why the solar wind reaches supersonic speeds and exactly which part of the Sun the particles come from.

One instrument in the SWEAP suite is the Solar Probe Cup. Most of the instruments on Parker Solar Probe stay safe and cool in the shadow of the heat shield, but the Solar Probe Cup is one of the few that sticks out. That’s so it can capture and measure particles streaming straight out from the Sun, and it had to go through some intense testing to get ready for this position in the Sun’s incredibly hot corona.

Credit: Levi Hutmacher/Michigan Engineering

The ISʘIS suite (pronounced EE-sis, and including the symbol for the Sun in its acronym) also measures particles. ISʘIS is short for Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun, and this instrument suite measures particles that move faster – and therefore have more energy – than the solar wind.

These measurements will help scientists understand these particles’ lifecycles – where they came from, how they got to be traveling so fast (these particles can reach speeds more than half the speed of light!) and what path they take as they travel away from the Sun and into interplanetary space.

2. Taking pictures – but not of the Sun’s surface.

WISPR (Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe) has the only two cameras on Parker Solar Probe – but they’re not pointed directly at the Sun. Instead, WISPR looks out the side of the spacecraft, in the direction it’s traveling, looking at the space Parker Solar Probe is about to fly through. From that vantage point, WISPR captures images of structures within the corona like coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. CMEs are clouds of solar material that occasionally explode from the Sun at millions of miles per hour. Because this solar material is magnetized, CMEs can trigger geomagnetic storms when they reach Earth – which, in turn, can cause effects like auroras and even, in extreme cases, power outages.

Right now, our observations of events like these come from satellites orbiting near Earth, so WISPR will give us a whole new perspective. And, scientists will be able to combine WISPR’s images with Parker Solar Probe’s direct particle measurements to get a better idea of how these structures change as they travel.

3. Studying electric & magnetic fields

The FIELDS instrument suite is appropriately named: It’s what scientists will use to study the electric and magnetic fields in the corona.

Electric and magnetic fields are key to understanding what happens, not only on the Sun, but throughout space, because they the primary driver accelerating charged particles. In particular, a process called magnetic reconnection – when magnetic field lines explosively realign, sending particles rocketing away at incredible speeds – is thought to drive solar explosions, as well as space weather effects on Earth, like the aurora.

FIELDS measures electric and magnetic field at high time resolution, meaning it takes lots of measurements in a short amount of time, to track these processes and shed some light on the mechanics underlying the Sun’s behavior. FIELDS’ measurements are precisely synced up with those of the SWEAP suite (one of the sets of instruments studying particles) so that scientists can match up the immediate effects that electric and magnetic fields have on the material of the solar wind.

Parker Solar Probe launches summer 2018 on its mission to study the Sun. Keep up with the latest on the mission at nasa.gov/solarprobe or follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

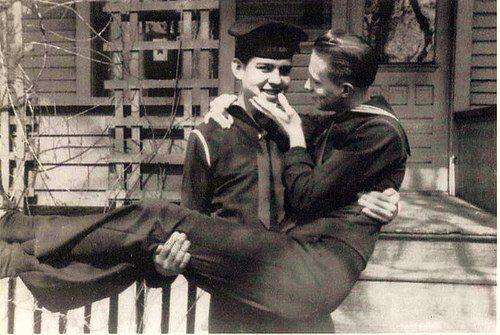

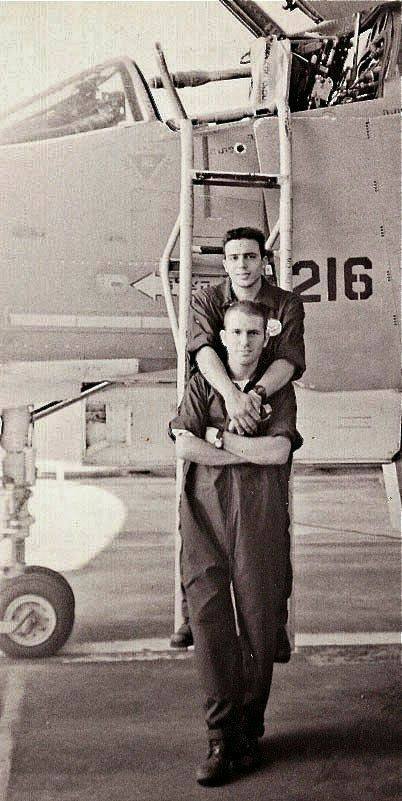

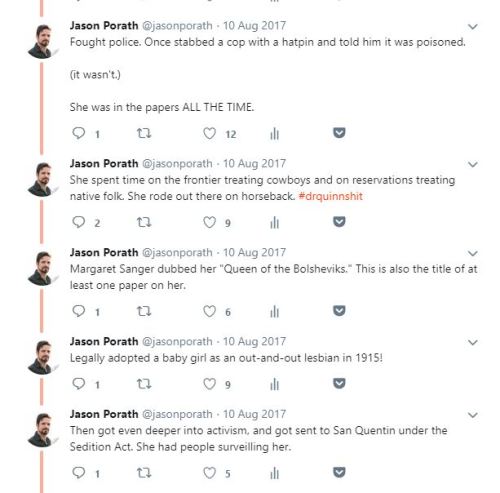

Marie Equi died on this day in 1952.

When I wrote that initial tweetstorm, I hadn’t finished all my research into her. It’s important to not leave out: Marie Equi was physically abusive and she almost certainly either cheated on her wife or went outside the bounds of their non-monogamous agreements. She was a deeply difficult, very flawed, very human person and one shouldn’t lose sight of that when talking about her.

And yes, I cover her in my second book.

A great, in-depth read – you may remember Moll Cutpurse from the first Rejected Princesses book. :)

-

tinylor liked this · 2 weeks ago

tinylor liked this · 2 weeks ago -

kutarinkishika liked this · 1 month ago

kutarinkishika liked this · 1 month ago -

unanocheenrio liked this · 1 month ago

unanocheenrio liked this · 1 month ago -

thehatphotograph reblogged this · 1 month ago

thehatphotograph reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ivalsoleunam liked this · 1 month ago

ivalsoleunam liked this · 1 month ago -

baby5milo liked this · 1 month ago

baby5milo liked this · 1 month ago -

neuroticgoblinnightmarewoman reblogged this · 1 month ago

neuroticgoblinnightmarewoman reblogged this · 1 month ago -

mitsuhachiinthehive reblogged this · 1 month ago

mitsuhachiinthehive reblogged this · 1 month ago -

mitsuhachiinthehive liked this · 1 month ago

mitsuhachiinthehive liked this · 1 month ago -

missgiffordavenue reblogged this · 1 month ago

missgiffordavenue reblogged this · 1 month ago -

anything-4-enchiladas reblogged this · 2 months ago

anything-4-enchiladas reblogged this · 2 months ago -

marinsomnia reblogged this · 2 months ago

marinsomnia reblogged this · 2 months ago -

jenoismysavior reblogged this · 2 months ago

jenoismysavior reblogged this · 2 months ago -

koushizzy liked this · 2 months ago

koushizzy liked this · 2 months ago -

princessuncertain liked this · 2 months ago

princessuncertain liked this · 2 months ago -

juiimoutoreblogs reblogged this · 2 months ago

juiimoutoreblogs reblogged this · 2 months ago -

jui-imouto-chan liked this · 2 months ago

jui-imouto-chan liked this · 2 months ago -

yeahcanigetuhhhhh reblogged this · 2 months ago

yeahcanigetuhhhhh reblogged this · 2 months ago -

yeahcanigetuhhhhh liked this · 2 months ago

yeahcanigetuhhhhh liked this · 2 months ago -

thethornpatch reblogged this · 2 months ago

thethornpatch reblogged this · 2 months ago -

orchid-house liked this · 2 months ago

orchid-house liked this · 2 months ago -

uuh-johns-wife11 liked this · 2 months ago

uuh-johns-wife11 liked this · 2 months ago -

do-not-forget-your-towel reblogged this · 2 months ago

do-not-forget-your-towel reblogged this · 2 months ago -

abbessolute reblogged this · 2 months ago

abbessolute reblogged this · 2 months ago -

polastristea liked this · 2 months ago

polastristea liked this · 2 months ago -

summerpoison liked this · 2 months ago

summerpoison liked this · 2 months ago -

lunolu liked this · 2 months ago

lunolu liked this · 2 months ago -

thev01dd reblogged this · 2 months ago

thev01dd reblogged this · 2 months ago -

mtraki reblogged this · 2 months ago

mtraki reblogged this · 2 months ago -

respectwomenjuice liked this · 2 months ago

respectwomenjuice liked this · 2 months ago -

zalazuri reblogged this · 2 months ago

zalazuri reblogged this · 2 months ago -

catseenonlybymoon reblogged this · 2 months ago

catseenonlybymoon reblogged this · 2 months ago -

jettatomy liked this · 2 months ago

jettatomy liked this · 2 months ago -

lunaraquaenby reblogged this · 2 months ago

lunaraquaenby reblogged this · 2 months ago -

kylalintu reblogged this · 2 months ago

kylalintu reblogged this · 2 months ago -

queer-feminist-thingies reblogged this · 2 months ago

queer-feminist-thingies reblogged this · 2 months ago -

jenjenthevirgo reblogged this · 2 months ago

jenjenthevirgo reblogged this · 2 months ago -

hells-prettiest liked this · 2 months ago

hells-prettiest liked this · 2 months ago -

ajokeaboutadog liked this · 2 months ago

ajokeaboutadog liked this · 2 months ago -

naijaboi liked this · 2 months ago

naijaboi liked this · 2 months ago -

sleepynegress reblogged this · 2 months ago

sleepynegress reblogged this · 2 months ago -

thejadedragone liked this · 2 months ago

thejadedragone liked this · 2 months ago -

withcass reblogged this · 2 months ago

withcass reblogged this · 2 months ago -

withcass liked this · 2 months ago

withcass liked this · 2 months ago -

kimmber liked this · 2 months ago

kimmber liked this · 2 months ago -

moonmunster reblogged this · 2 months ago

moonmunster reblogged this · 2 months ago -

moonmunster liked this · 2 months ago

moonmunster liked this · 2 months ago -

acethembo reblogged this · 2 months ago

acethembo reblogged this · 2 months ago -

acethembo liked this · 2 months ago

acethembo liked this · 2 months ago -

bruxadepano reblogged this · 2 months ago

bruxadepano reblogged this · 2 months ago