Dear Fandom

Dear Fandom

Can we please stop berating and calling for the death of creators because you disliked creative decisions they made.

More Posts from Ignorethisrandom and Others

Mary Queen of Scots Documents.

In February 2013 I read that the John Gray Centre in Haddington had found documents relating to Mary Queen of Scots, and you could go see them. I arrived at there a few days later and was disappointed to see no sign of them, so I enquired and was directed to a lady who said, yes they had them but were not on open display……but she could go bring them to me and let me see them!!!!

Wow there I was minutes later with the letter spread out before me and me, with a pair of white gloves, was allowed to actually handle these historic items that Mary had approved almost 450 years before!

The document dates from March 1566, when Mary had just returned to Edinburgh after fleeing to Dunbar castle and has witnessed the murder of her secretary David Rizzio just two weeks previously. It is a grant of church land to the Burgh of Haddington. While this document was not signed by Mary it is appended with an almost perfect example of her great seal.

Although in Latin and therefore unreadable to most it is a visually beautiful item with fine handwriting and of course the wax seal, I was surprised how large the seal was but the lady in the archives explained it was only personal seas that were smaller, usually on a stamp or as I imagined a ring. This would have been written by a clerk for the queen and is in near perfect condition, the white things you see on the pictures are lead weights to hold the document open as it has been fold for most of its 447 years!

The other document is more fragile and has been enclosed in a plastic case to protect it. This is a letter signed by Queen Mary and King Henry, aka Lord Darnley. The document is asking the burgesses of Haddington to remain at home from the various raids that were happening at the time. I find it amazing that these pieces of history are not just there to be viewed(on request) but that you can get up close and personal with them.

The John Gray Centre is East Lothian’s archives, a museum and local history services, it is free to visit and it was free for me to ask to see things held in the archive, the only thing you are charged for is if you want to take some pics, the fee then was a one off £5.

Caption: How your day is actually going.

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

History Edits: Jean Stewart, Countess of Argyll

Perhaps best known as the only sister of the infamous Mary, Queen of Scots, Jean Stewart had her own adventurous life, occupying the various roles of king’s daughter, honoured lady-in-waiting, unhappy spouse, outlaw, and excommunicant over the decades. Born in the early 1530s, she was the only certainly acknowledged* illegitimate daughter of King James V. Her mother was probably Elizabeth, a member of the sprawling, yet influential and ambitious Beaton family. On her father’s side, Jean’s numerous half-siblings included James Stewart, Commendator of St Andrews who was also the future earl of Moray and Regent of Scotland; his older half-brother and namesake James Commendator of Kelso (d.1558); John Stewart Commendator of Coldingham; and Robert Stewart, Earl of Orkney, as well as her younger half-sister, Mary Stewart, who became queen of Scots at no more than a week old upon the death of their father in 1542.

As the king’s daughter she was raised at court in considerable comfort, and the Treasurer’s Accounts record various payments for her clothing, nurse, and upbringing-including payments for gowns, a canopy for her to travel under, massbooks, and mourning clothes after the death of her grandmother Margaret Tudor in 1541. Her brothers often travelled between court and St Andrews where they were being educated, but Jean was more permanently associated with the royal court. When her father married his second wife Mary of Guise, the new queen apparently took Jean under her wing, and brought her step-daughter into her own household. Jean briefly moved to the household of her first legitimate brother Prince James, who was born in 1540, but when the infant prince died the next year she returned to the queen’s household. After 1542, when her father died and the succession of the infant Mary ushered in a new period of strife, references to Jean are less frequent. However, we at least know that when her royal sister sailed for France in 1548, Jean did not travel with her, unlike several of her brothers and at least two of her cousins, (Mary Fleming and Mary Beaton). Instead, in 1553, by which time Jean was in her early twenties, Mary of Guise and the Regent Arran arranged for her to marry Archibald Campbell, Lord Lorne, and the wedding took place in April the following year. Her new husband succeeded his father as 5th earl of Argyll five years later in 1558. By that point, both Argyll and his close friend James Stewart, Commendator of St Andrews- Jean’s half-brother- had converted to Protestantism. Though her own religious views are more of a mystery, the ideals of the new reformed faith, which was formally established in Scotland in 1560, were to play an important role in her life.

When Queen Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, she soon re-established links with her birth family, and several of Mary’s half-siblings regularly attended on her at court, though their relationships with the queen varied. The Countess of Argyll quickly renewed ties with the younger sister whom she had not seen since Mary was five years old, and though she is not as well-known as the infamous Four Maries, Jean served as one of her sister’s chief ladies-in-waiting for several years. “Ma soeur” received gifts of clothes and jewels from the queen, along with an annual pension of £150 pounds. Along with Agnes Keith (who married Jean’s brother James and became Countess of Moray in 1562) and Annabella Murray, Countess of Mar, Jean was one of the ladies Lord Darnley later blamed for causing a rift between himself and his wife. At the christening of Queen Mary’s only son, the future James VI, in June 1566, Jean and the Earl of Bedford stood proxy for Elizabeth I of England as the child’s godmother. A few months earlier, on the fateful night of 9th March 1566, Jean had been the only other woman in the room when David Rizzio was murdered, though among the men present at the dinner were her half-brother Robert Stewart and her kinsman Beaton of Creich. Jean is supposed to have caught a candelabra when the table was knocked over in the struggle, preventing the room being plunged into complete darkness. Though both her half-brother the Earl of Moray and her husband the Earl of Argyll must have been aware that there was a plot to murder Rizzio, it is unclear whether Jean was forewarned. In any case it seems unlikely that her husband would confide in her, since by 1566 the couple had been estranged for years.

Jean was a proud and determined yet often stubborn woman, and does not appear to have relished having to leave the Lowlands and court life for mountainous Argyll. Her husband was unfaithful on several occasions but does not appear to have been willing to tolerate his wife’s own infidelity, if the accusations of adultery levelled at her in the late 1550s are at all truthful. Relations steadily worsened between the couple, and Jean later alleged that, in the summer of 1560, she had been held prisoner and intimidated by several of her husband’s Campbell kinsmen. Though Jean was briefly reconciled with Argyll through the intervention of mutual friends, including the reformer John Knox, by 1563 things had deteriorated again. This time Queen Mary and John Knox made a rare collaborative effort in an attempt to reconcile the warring spouses. Mary considered Argyll a close friend and important ally and could not risk offending him, yet at the same time she was fond of her sister, and in any case their public feuding was considered an embarrassment to both the reformed faith and the royal family. While Knox gave Argyll a thorough dressing down for his infidelity and refusal to patch things up with his wife, the queen warned Jean that should she ‘behave not herself as she ought to do, she shall find no favour of me’.

In 1567, Argyll joined with many other Scottish nobles, both Catholic and Protestant, in imprisoning Queen Mary, but baulked at the idea of deposing her. He later commanded the Queen’s Men at the Battle of Langside in 1568 and subsequently became one of her chief lieutenants in Scotland after she fled to England in the same year. Meanwhile, by 1567 his marriage had completely broken down. After Jean escaped yet another bout of imprisonment in one of her husband’s retainers’ castles, refusing return to her husband, the earl finally initiated divorce proceedings. In order to settle the matter quickly, Jean was offered 10,000 merks in return for agreeing to a divorce on the grounds of her husband’s adultery. But although she certainly had no intention of reuniting with Argyll, she refused to cooperate in the divorce- whether this was due to personal morality or because she wanted to protect her status as countess is unclear. In this she was supported by her half-brother the Earl of Moray, now Regent of Scotland for the young James VI. Moray had also fallen out with Argyll over politics by this point and, though both men remained Protestant, Moray seems to have been very opposed to divorce (like Knox, who also berated Argyll for his behaviour). Moray publicly backed his sister and occasionally offered her financial support, as did other members of his extended family and Jean’s friends, like Annabella Murray (Moray’s aunt and another of Queen Mary’s former ladies-in-waiting). Frustrated over her refusal to grant him the divorce he needed, Argyll now attempted to compel his wife to return to him through the courts, but she refused to do so, leaving both spouses, the Kirk, and the political community in a bind. After Moray’s assassination in early 1570, Jean lost an important source of support from a close family member, and though her distant cousin the earl of Atholl attempted to intercede for her with Argyll, a reconciliation still never materialised. Holding out for a much more substantial settlement from her husband, whom she described as ‘that ongrait man’, Jean, took up residence with her friend Annabella Murray (Countess of Mar and James VI’s ‘Minnie’) at Stirling, with the household of the young king James. At this time she seems to have been acutely aware that she lacked a network of support, being described as ‘very angry and in great poverty’, and her situation worsened over the next few years.

In the early 1570s, the balance began to shift in favour of Argyll, who had turned to the church courts for a solution. Kirk officials repeatedly censured Jean for non-adherence to her husband: she ignored all of these warnings. When she continued to disobey the direct orders of the Kirk, she was put to the horn (outlawed), and not long afterwards, with nowhere else to turn, she took refuge in Edinburgh Castle. The castle was then undergoing the ‘Lang Siege’, with William Kirkcaldy of Grange and his men holding the castle on behalf of Queen Mary against the Regent Morton, who then governed Scotland on behalf of Mary’s son the young King James VI. This siege has gone down in Edinburgh’s history as infamous, and forever changed the shape of the castle itself. The garrison held out for three years, taking potshots at both the supporters of the young King James and the capital city at large, minting coins in Mary’s name, and housing numerous members of the Queen’s Men, including Mary’s former secretary the ‘machiavellian’ William Maitland of Lethington, as well as many other dissidents who had entered the castle for various reasons, Jean included. Though her sentence of outlawry was briefly relaxed to allow her to appear in court, Jean refused to leave the castle and was excommunicated by the Kirk in April 1573.

By this time the Earl of Argyll had finally been won over by the ‘King’s Men’ and had exchanged his allegiance to Queen Mary for a position as chancellor in the government of James VI. This enabled him to get an act of parliament passed that allowed divorce for desertion and, finally, in June 1573, Argyll legally divorced his wife. This was a landmark decision in the history of Scots law, and while Jean never accepted the divorce, her tumultuous personal life did result in the emergence of the concept of ‘divorce by desertion’ and one of the first, and certainly most famous, divorces granted by the new reformed Church of Scotland. In desperate need of an heir, her ex-husband Argyll quickly remarried, but died only three months later in September 1573, with his posthumous son by his new wife dying at birth the next year.

Only a few weeks before Jean’s divorce was announced, Edinburgh Castle had finally surrendered, having been so thoroughly bombarded by English troops that David’s Tower and the Constable’s Tower, both roughly two hundred years old, collapsed in to the main entrance of the castle. Though most of the garrison were allowed to leave freely, Kirkcaldy of Grange and his brother were hanged at the mercat cross of Edinburgh along with the jewellers who had minted the coinage in Mary’s name. Maitland of Lethington died suspiciously in prison not long afterwards, possibly by his own hand. Jean, still afraid that she would be handed over to her husband, had written to Elizabeth I of England beseeching her protection, and in the meantime crossed the water to Fife, her mother’s native county. In time though, with her husband preoccupied with his remarriage and then dying soon after, Jean actually emerged in a stronger position. For the next decade or more she harassed her brother-in-law, the new earl of Argyll (who had married the Regent Moray’s widow Agnes Keith), for a settlement which would give her financial security, claiming her right as the late earl’s widow over his ‘pretendit’ second wife. She eventually won this case, receiving a handsome pay-out which supported her to the end of her life. She seems to have spent her later years living comfortably in Edinburgh, still describing herself as the Countess of Argyll. She was legitimated by the Crown in 1580, some decades after several of her half-brothers. She lived just long enough to hear of the execution of her younger sister Mary in 1587, but her thoughts on that infamous event must remain a mystery. By this point only Jean and her half-brother Robert, Earl of Orkney remained of James V’s acknowledged children: James of Kelso had died young in 1558, John Stewart succumbed to illness in 1563, the Regent Moray was shot in 1570, and now Mary had been beheaded. In January 1588, possibly aged about 55, Jean herself died in Edinburgh, ending her dramatic career a wealthy widow. She was buried in the royal vault at the Abbey of Holyrood, next to her father King James V.

Sources below cut or, since that ‘read more’ thing isn’t showing up much, you can access them at the bottom of this page

Keep reading

Historical fiction writers and historians like to talk about the whole “Edward abandoned pregnant Isabella to save Piers Gaveston” thing (which is entirely fake btw) but I think we should focus more on that One Time In Tynemouth when Isabella faced the possibility of an attack by the Scots because, while it’s actually an event with very little historical significance, I think it had a tremendous impact on the people directly involved in it, as it seems to have been a major trigger in the deterioration of Edward and Isabella’s relationship, which she fully blamed on Hugh le Despenser but it also appears to be one of the rare instance where Hugh was genuinely not trying to fuck her over in any shape or form.

In October 1322, Edward was dealing with the aftermath of yet another failed Scottish campaign, which included Robert Bruce invading back England. Bruce quickly marched toward where the King was at the moment, wreaking havoc as one generally do during a punishing invasion and, by mid-October, Edward was forced to flee, abandoning a whole bunch of his material possessions behind him.

The situation would have already been humiliating enough but it sparked another problem: at the moment, Isabella had been residing at Tynemouth, a little less than a hundred miles away from her husband. While there’s no clear indication that Bruce was planning to walk toward this direction or had any plan to take the queen hostage, it’s undeniable that Isabella herself believed it and was terrified.

It’s always a bit sketchy to try and gage the feelings of people who have been dead for hundreds of years (if anything, it’s also risky to try and assume the feelings of living people too so…) but in this particular case, I really do think we may reasonably argue that it was one of the most traumatic event in her life and she entirely blamed Hugh le Despenser for it, accusing him of ‘falsely and treacherously counselling the king to leave my lady the queen in peril of her person’ at Tynemouth.“, which is straight up factually incorrect.

I won’t try to debate whether or not she was in actual physical danger, partially because I don’t know enough about Robert de Bruce and his military tactics to gage whether or not he may have been interested in taking her hostage (but it honestly feels unlikely, at least in the circumstances…) but we know for a fact that even if Hugh actually did advised Edward to let his wife to rot alone at Tynemouth, that’s not what Edward actually did.

We still have a high number of letters showing Edward’s concern for his wife and he quickly charged some of his most trusted men with the task to go safely fetch the queen. The problem here is that his most trusted men obviously included some of Hugh’s subordinates. Isabella reacted to the situation just as well as you may imagine: she categorically refused to leave with Hugh’s men, not under any circumstances whatsoever. I don’t think her fear was entirely irrational: she had already gone on her knees to beg for Hugh’s banishment and I do think she may have been afraid of him using this occasion to get his revenge.

Now, I’m still not sure if Hugh ever actually intended to get rid of the queen (my opinion on that changes all the time tbh) but even if he did, I’m entirely sure he was not planning to do so here. First, there’s the fact that even if some of his men were present, he wasn’t there to command them and Isabella had no reason to distrust the actual commander present. Most importantly, Hugh’s own wife Eleanor, who had been a member of the queen’s household pretty much since she had set foot in England was also present. Hugh was a reckless man who cared very little about who he had to destroy to reach his goals but he appears to have sincerely care for his close family and it’s highly improbable that he would have voluntarily put her in a harm way, even to get back at the queen, especially since she was most likely pregnant too at the moment.

The situation must have been incredibly messy. Both Isabella and Eleanor were heavily pregnant (or Eleanor’s case, may have just given birth) and their relationship, that had been a stable and friendly one for years, since they were both little more than children, had probably been deteriorating for some time due to their husbands’ affair. Eleanor probably desperately wanted to escape with her husband’s men and Isabella’s clear and definite refusal probably felt like a knee kick in the gums.

The fact that two of Isabella’s ladies died as a direct consequence of their escape, one of them who was also pregnant and passed away shortly after prematurely giving birth was probably even more traumatic for both of them, as was the fact that the third man send by Edward to rescue the queen was actually caught by the Scots and taken hostage, which had been Isabella’s worst fear since the very beginning

Even if all technically ended well (except for those two poor ladies-in-waiting, obviously) and even if most contemporary chroniclers appear to have found the whole event fairly insignificant in the grand scheme of things, it’s pretty clear that it worsened the deterioration of marriage of Edward and Isabella, if it didn’t kickstarted it; before 1322, Edward and Isabella spent a lot of time together, even when it was not strictly necessary and we have a profusion of letters from one to the other when they were separated.

In 1322-1323, the time they spent together had shrunk to next to nothing and there’s few letters remaining to indicate that they keep contact when they were away from each other. In fact, there’s times during those two years when Edward himself was pitifully vague about the exact whereabouts of his wife, which lead me to believe that he had either temporarily casted her away from court or that she herself had decided to stay away from him (probably a mix of the two) and that he was trying to save face.

Now, what I find the more interesting is that I can easily understand the point of view of every person implicated in this situation. Isabella must have felt like her husband had abandoned her and only 'rescued’ her by sending her her worst enemy’s delegates. The fact that her contemporaries seems to have seen the situation as a non-issue and that even Hugh’s worst detractors didn’t blame him for anything, for once (the pope himself actually commended him for the way his men had acted…) must have been even more enraging for her.

Eleanor probably felt like her queen and friend had not only gravely offended her husband (and by extension her family and herself) once again but also put them all in danger for no logical reason. Edward was clearly worried for his wife at first but her refusal to cooperate was probably mind-boggling to him at first and then insulting, especially when it become obvious that she was not planning to get over it.

As for Hugh…If there’s one thing we know about Hugh’s personality, it’s that he was very good at making himself the victim in even the situations where he was the most blatantly at fault. Now, considering that he already disliked Isabella before the whole thing, can you imagine how he saw it and what he had to tell Edward about it? It must have been something along the lines of: "Your wife essentially spat in your face by refusing the help you sent her and claiming you had done nothing useful, she offended me once again and still claimed it was somehow my fault and she also endangered my wife and unborn child, what kind of unnatural, hateful woman would behave in such a way toward her king and husband? How can you take that?” Fuck, he may even have truly believed that.

Now I’m not gonna say it’s the one thing that really determined the rest of their relationship (there was already A Lot going on long before that and there was much more to come for all of them) but I do think it was a pretty major element of how things managed to go so bad so fast and I also find it pretty telling that Isabella would later accuse Hugh of forcing her husband to abandon her to mortal danger even if absolutely no one else seems that it was what happened when it actually happened…

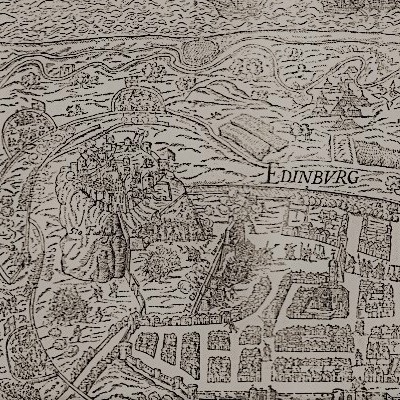

A view of Edinburgh in 1560, the year Scotland formally adopted Protestantism as the national religion.

I think the book series might work better as a HBO or Showtime or Starz or Netflix mini-series able to go all out in terms of the grittiness, sex, and violence of the book.

‘Red Sparrow’ Post-Mortem And Why The Sequels Deserve To Be Made

WARNING: This post contains major spoilers for Red Sparrow (original Jason Matthews book, 2015 Eric Warren Singer screenplay draft and Francis Lawrence’s film) as well as minor story details from sequel novels Palace of Treason and The Kremlin’s Candidate. For my thoughts on the film, head to Letterboxd.

I can’t seem to muster up some sort of pretentious intro, so getting right to it:

Keep reading

You can appreciate BookSansa and ShowSansa at the same time too.

you had an anon a while back who said that sansa was antagonistic at the end of the show, and i agree that she was at least unrecognizable compared to her book counterpart. she's sapped of the kindness and courtesy that defined her in the books. an example is how she tells edmure to sit down in the finale. book sansa would never humiliate her uncle like that.

That's kind of an unfair comparison because show!Sansa's story is also very different. The show veered away from her actual arc early on (nice!Hound, nice!Tyrion, no Vale arc, Ramsay... etc) and utterly de-emphasized her thematic connection to storytelling and idealism and romance.

Show!Sansa is consistent within the story the show chose to tell, more so than many other characters. She makes sense at the end, the stupid Edmure moment notwithstanding.

But she is very much a different character entirely from book!Sansa.

My Montage Of Lost Things…

Florence + the Machine “Prayer Factory”

Ideas for Season 2

What if next season the writers kept up the unreliable narrator device?

There could be an episode next season centering on the Massacre at Vassy - the start of the many wars of religion - where Louis de Bourbon (Prince of Conde) tells Ramira HIS side of the story. In his version he is the only one fighting for Protestants to have the same freedoms and rights as everyone else. This would make for a more rounded character and an interesting look at how Louis sees himself. With his narration he becomes a freedom fighter for the oppressed. Protestants can’t teach/study at Universities, hold certain jobs, worship in public in many cities/provinces. He sees himself as the Huguenots’ savior in many ways–their version of Martin Luther King Jr. He can even physically look thinner and more dignified instead of fulfilling the short/fat one dynamic he has with Antoine when Catherine is narrating.

Since other shows set in this time period do not have the unreliable narrator device, this show should use it to their advantage. This story is filled with people manipulating each other–why not manipulate the audience while you’re at it?

Plus it gives Ramira some internal conflict: who does she believe? Maybe Catherine could try to make her into one of her Flying Squadron (spy/seductresses) but Ramira doesn’t like this, so hearing Louis’s side of the story could help bring tension between her and Catherine, giving Ramira something to do next season since historically she never existed and could easily be overshadowed by the show’s historical figures and events.

-

ignorethisrandom reblogged this · 5 years ago

ignorethisrandom reblogged this · 5 years ago -

ignorethisrandom liked this · 5 years ago

ignorethisrandom liked this · 5 years ago -

silvershewolf247 reblogged this · 7 years ago

silvershewolf247 reblogged this · 7 years ago