The Two Types Of Pacing

The Two Types of Pacing

Pacing is a tricky, tricky thing. Hopefully, by breaking it down into two schools of thought, we can better our understanding of maintaining effective pacing.

as requested by @whisperinghallwaysofmirrors

First, Some Definitions

According to Writer’s Digest, narrative pacing is “a tool that controls the speed and rhythm at which a story is told… [H]ow fast or slow events in a piece unfold and how much time elapses in a scene or story.“

Pacing can be a lot of things. Slow, fast, suspenseful, meandering, boring, exciting, et cetera et cetera. While we don’t want meandering or boring, getting it to be the other things can be a feat.

As I go through all of this, I would like to say that the number one thing you should be keeping in mind with the pacing of your story is the purpose.

What is the purpose of this story, scene, dialogue, action, arc, plot point, chapter, et al? This and only this will keep you on track the whole way through.

Without further ado, here are the two types of pacing…

Micro Pacing

This, to me, is the harder of the two. Macro pacing usually comes naturally with our understanding of overall story structure that we see in books and movies. Micro is much more subjective and labor-intensive.

The first step of every scene you write is to identify what kind of pacing it needs to be effective. Is a slower pace going to nail in the emotional tone? Is a faster pace going to convey how urgent the scene is? Is choppy going to show how chaotic it is? How much attention to detail is needed? Et cetera. And even with the scene’s tone, there are also tones within with action, dialogue, and narrator perception.

There is no one-size-fits-all trick to mastering pacing. All you can do is try to keep it in mind as you draft. Don’t let it consume you, though. Just get it down. After drafting, look at the pacing with a critical eye. Do important scenes go too fast? Are unnecessary things being dragged out? Is this scene too detailed to be suspenseful?

A lot of errors in pacing are quick fixes. The adding or removal of details, shortening or lengthening of sentences, changing descriptions. However, these quick fixes do take a while when you have to look at every single scene in a story.

Macro Pacing

Rather than the contents of a scene, this deals with everything larger. Scenes, chapters, plot points, storylines, subplots, and arcs. This is taking a look at how they all work for each other when pieced together.

One of the biggest resources when it comes to analyzing macro pacing is story structure philosophy. The common examples are Freytag’s Pyramid, the 3-Act Structure, Hero’s Journey, and Blake Snyder’s 15 Beats. They follow the traditional story structure. Exposition, catalyst, rising action, climax, and resolution (albeit each in different terms and specificity). Though some see it as “cookie-cutter”, 99% of effective stories follow these formats at a considerable capacity. It’s not always about how the story is told, but rather who tells it. But I digress.

Looking at these structures, we can begin to see how the tried-and-true set-up is centered around effective pacing.

The beginning, where everything is set up, is slower but short and sweet. The catalyst happens early and our MC is sent out on a journey or quest whether they like it or not. The trek to a climax is a tricky stage for maintaining effective pacing. Good stories fluctuate between fast and slow. There is enough to keep it exciting, but we’re given breaks to stop and examine the finer details like theme, characterization, and arcs.

The edge before the climax is typically when the action keeps coming and we’re no longer given breaks. The suspense grabs us and doesn’t let go. This is the suspense that effectively amounts to the crescendo and leads to the emotional payoff and release that follows in the resolution. The resolution is nothing BUT a break, or a breather if you will. Though it is slower like the exposition, it is longer than that because this is where we wrap everything up for total closure. This is what the reader needs, rather than what they want. So you can take your time.

Not every story has to follow this recipe step-by-step. Critically acclaimed movies such as Pulp Fiction, Frances Ha, and Inside Llewyn Davis* break the traditional structure. However, they still keep certain ingredients in it. Whether it be the concept of a climax, the idea of a journey, or the overall balance of tension and release.

If you’re struggling with the macro side of your story’s pacing, I would try to identify what the weakest areas are and see if applying these story structure concepts and methodology strengthens it at all. If not, it may be that your story idea doesn’t fit the “substance” requirement of an 80k+ word novel. It may need more or fewer subplots or an increase of conflict or more things getting in the MC’s way. You could also see if adapting it to a shorter medium (novella, et al) or a longer medium (series, episodics, et al) would alleviate the pacing issues.

*sorry all my references are movies and not books, but I’ve seen more movies than I’ve read books

In Short–

Pacing, both macro and micro, are incredibly subjective concepts. The only way to really find out how effective your story’s pacing is, is to look at it through the lens of traditional structures and ask for feedback from beta readers. How a reader,who doesn’t know the whole story like you do feels about pacing is the best resource you could have.

More Posts from Lrs35 and Others

i get a little bit of free time and start going "what if i taught myself woodworking" girl work on ur resume

in many ways being alive is about opening your curtains after getting out of bed

for all you literature babes, here is an open yale course which ive been listening to which includes lectures and course materials and is totally free. it’s v interesting enlightening etc, have fun!!

A.F. Vandevorst installation for Arnhem Mode Biennale 2011

“A girl sleeping in a hospital bed in her A.F. Vandevorst dress. But here, the girl as well as the mattress and pillow are made out of candle wax. Once lit, what starts as a perfect image will slowly melt and perish during the biennale.”

(by natalie moonbeam)

i just think they are always on the kitchen floor you know what i mean. like they’ve lived in this shoebox flat two months now but can’t be fucked to buy any furniture all they’ve got is a scratchy red sofa and some bookshelves and as a table they’re using a flipped-over cardboard box that’s got peeling tape and ‘records books other shit’ written on the side in blue marker it’s waterlogged and has mug rings on both sides and that’s all they have so they’re just sitting on the kitchen floor sleep-rumpled in pjs eating their toast in the morning and sitting on the kitchen floor in silence after moons and missions covered w dirt and blood and bruises and some nights they’re sitting on the kitchen floor passing a bottle of cheap liquor between them and they’re laughing and listening to records and sharing a joint and the window is open w a breeze coming through and also sometimes they’re sitting on the kitchen floor eating cereal in the middle of the night w their knees touching sneaking little glances at each other and other times they are fucking on that kitchen floor and other other times they are just quietly saying i love you. on the kitchen floor.

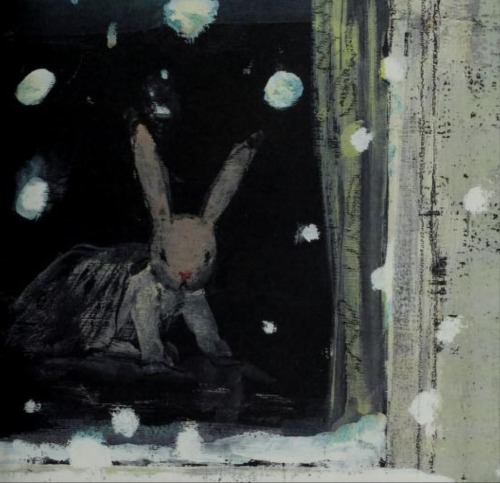

komako sakai, the snow day

thinking about that one quote from the simpsons about how much homer misses marge

-

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 2 months ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 2 months ago -

roselyn-writing liked this · 4 months ago

roselyn-writing liked this · 4 months ago -

transparententhusiastmentality liked this · 4 months ago

transparententhusiastmentality liked this · 4 months ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 5 months ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 5 months ago -

jaigrefs reblogged this · 6 months ago

jaigrefs reblogged this · 6 months ago -

neptunethefool reblogged this · 6 months ago

neptunethefool reblogged this · 6 months ago -

animeschibia reblogged this · 7 months ago

animeschibia reblogged this · 7 months ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 8 months ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 8 months ago -

sweetcookiesjar reblogged this · 9 months ago

sweetcookiesjar reblogged this · 9 months ago -

heckcareoxytwit liked this · 9 months ago

heckcareoxytwit liked this · 9 months ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 9 months ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 9 months ago -

newdawnhorizon reblogged this · 10 months ago

newdawnhorizon reblogged this · 10 months ago -

thepointlessmasterpiece liked this · 10 months ago

thepointlessmasterpiece liked this · 10 months ago -

tanknamedjunseok reblogged this · 11 months ago

tanknamedjunseok reblogged this · 11 months ago -

nix-writes reblogged this · 1 year ago

nix-writes reblogged this · 1 year ago -

thevoidisloudandwantsorangejuice liked this · 1 year ago

thevoidisloudandwantsorangejuice liked this · 1 year ago -

myfairverona liked this · 1 year ago

myfairverona liked this · 1 year ago -

pentaqola liked this · 1 year ago

pentaqola liked this · 1 year ago -

floraliarites liked this · 1 year ago

floraliarites liked this · 1 year ago -

opossumjournal reblogged this · 1 year ago

opossumjournal reblogged this · 1 year ago -

thepointlessmasterpiece reblogged this · 1 year ago

thepointlessmasterpiece reblogged this · 1 year ago -

the-almighty-m liked this · 1 year ago

the-almighty-m liked this · 1 year ago -

opossumjournal liked this · 1 year ago

opossumjournal liked this · 1 year ago -

lichbug liked this · 1 year ago

lichbug liked this · 1 year ago -

xeon2222 reblogged this · 1 year ago

xeon2222 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

h-2-h0eee liked this · 1 year ago

h-2-h0eee liked this · 1 year ago -

spitefulbull liked this · 1 year ago

spitefulbull liked this · 1 year ago -

obsessive-fangirl-and-writer reblogged this · 1 year ago

obsessive-fangirl-and-writer reblogged this · 1 year ago -

bellascarousel reblogged this · 1 year ago

bellascarousel reblogged this · 1 year ago -

bellascarousel liked this · 1 year ago

bellascarousel liked this · 1 year ago -

cryscal-writes reblogged this · 1 year ago

cryscal-writes reblogged this · 1 year ago -

cryscal liked this · 1 year ago

cryscal liked this · 1 year ago -

zenari-astralis reblogged this · 1 year ago

zenari-astralis reblogged this · 1 year ago -

zenari-astralis liked this · 1 year ago

zenari-astralis liked this · 1 year ago -

disneyfloppins liked this · 1 year ago

disneyfloppins liked this · 1 year ago -

nvmechapter reblogged this · 1 year ago

nvmechapter reblogged this · 1 year ago -

boreaswrites liked this · 1 year ago

boreaswrites liked this · 1 year ago -

raindroppoetry liked this · 1 year ago

raindroppoetry liked this · 1 year ago -

yuerstruly liked this · 1 year ago

yuerstruly liked this · 1 year ago -

tonberry-princess liked this · 1 year ago

tonberry-princess liked this · 1 year ago -

reikaryuu-blog liked this · 1 year ago

reikaryuu-blog liked this · 1 year ago -

freezi-drink liked this · 1 year ago

freezi-drink liked this · 1 year ago -

paranoidpancakes reblogged this · 1 year ago

paranoidpancakes reblogged this · 1 year ago -

allthingswriting reblogged this · 1 year ago

allthingswriting reblogged this · 1 year ago -

qveenbpd reblogged this · 1 year ago

qveenbpd reblogged this · 1 year ago -

cranberrynoname reblogged this · 1 year ago

cranberrynoname reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mecagoentuputamadre liked this · 1 year ago

mecagoentuputamadre liked this · 1 year ago -

ididntknowthat reblogged this · 1 year ago

ididntknowthat reblogged this · 1 year ago