Minirosebush

More Posts from Minirosebush and Others

Mark Laver - Back in black, 2021

Pokemon Patches made by PewterCityTradingCo

Daily update (10)

Urgent and dangerous 13-07-2024

We miraculously survived. The occupation army had just committed a horrific massacre in the camp next to us, resulting in more than 100 martyrs and more than 289 injuries, including serious ones, to date. Medical teams are still recovering martyrs to this moment.

This child was martyred while in her mother's arms. Her mother was not photographed because the sight of the corpse was painful, consisting of pieces of flesh.

This girl's father and mother were martyred

This woman martyred her entire family

Bombing a civil defense vehicle

Other pictures from the massacre of the place that the occupation claimed was safe - Mawasi Khan Yunis

Despite everything that surrounds us, and despite the fact that death is closer to us than life, there is still a glimmer of hope to rebuild our home and return to normal life. Help as much as you can.

Details of the massacre are not over Follow the update in the comments.

Please contact these people and send the post to them to share widely

@nabulsi @sar-soor @appsa @akajustmerry @annoyingloudmicrowavecultist @feluka @marnota @el-shab-hussein @sayruq @tortiefrancis @sayruq @tsaricides @riding-with-the-wild-hunt @vivisection-gf @belleandsaintsebastian @ear-motif @kordeliiius @communistchilchuck @brutaliakhoa @raelyn-dreams @troythecoop @the-bastard-king @tamarrud @4ft10tvlandfangirl @queerstudiesnatural @northgazaupdates2 @90-girlfriend @skatehani @awetistic-things @baby-girl-aaron-dessner

After losing everything, I started to feel happy to receive a free food carton ..

Today I walked for two hours to get it to provide food for my parents 🥲

Please help me cover the travel costs for me and my family. War life is very tiring especially for my parents who is suffering everyday because lack of food, medicine and hospitals 😢

Please keep sharing and donatind as much as you can, every 5$ can help us to escape to a safe place and start a new life 🙏

Excerpts from an interview with Assata Shakur in Cuba in 1997:

Sociologist Christian Parenti: How did you arrive in Cuba?

Assata Shakur: Well, I couldn’t, you know, just write a letter and say, “Dear Fidel, I’d like to come to your country.” So I had to hoof it–come and wait for the Cubans to respond. Luckily, they had some idea who I was, they’d seen some of the briefs and U.N. petitions from when I was a political prisoner. So they were somewhat familiar with my case and they gave me the status of being a political refugee. That means I am here in exile as a political person.

Parenti: How did you feel when you got here?

Shakur: I was really overwhelmed. Even though I considered myself a socialist, I had these insane, silly notions about Cuba. I mean, I grew up in the 1950s when little kids were hiding under their desks, because “the communists were coming.” So even though I was very supportive of the revolution, I expected everyone to go around in green fatigues looking like Fidel, speaking in a very stereotypical way, “the revolution must continue, Companero. Let us triumph, Comrade.” When I got here people were just people, doing what they had where I came from. It’s a country with a strong sense of community. Unlike the U.S., folks aren’t so isolated. People are really into other people. Also, I didn’t know there were all these black people here and that there was this whole Afro-Cuban culture. My image of Cuba was Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. I hadn’t heard of Antonio Maceo (a hero of the Cuban war of independence) and other Africans who had played a role in Cuban history.The lack of brand names and consumerism also really hit me. You go into a store and there would be a bag of “rice.” It undermined what I had taken for granted in the absurd zone where people are like, “Hey, I only eat uncle so and so’s brand of rice.”

Parenti: So, how were you greeted by the Cuban state?

Shakur: They’ve treated me very well. It was different from what I expected; I thought they might be pushy. But they were more interested in what I wanted to do, in my projects. I told them that the most important things were to unite with my daughter and to write a book. They said, “What do you need to do that?” They were also interested in my vision of the struggle of African people in the United States. I was so impressed by that. Because I grew up–so to speak–in the movement dealing with white leftists who were very bossy and wanted to tell us what to do and thought they knew everything. The Cuban attitude was one of solidarity with respect. It was a profound lesson in cooperation.

Parenti: Did they introduce you to people or guide you around for a while?

Shakur: They gave me a dictionary, an apartment, took me to some historical places, and then I was pretty much on my own. My daughter came down, after prolonged harassment and being denied a passport, and she became my number one priority. We discovered Cuban schools together, we did the sixth grade together, explored parks, and the beach.

Parenti: She was taken from you at birth, right?

Shakur: Yeah. It’s not like Cuba where you get to breast feed in prison and where they work closely with the family. Some mothers in the U.S. never get to see their newborns. I was with my daughter for a week before they sent me back to prison. That was one of the most difficult periods of my life, that separation. It’s only been recently that I’ve been able to talk about it. I had to just block it out, otherwise I think I might have gone insane. In 1979, when I escaped, she was only five years old.

Parenti: You came to Cuba how soon after?

Shakur: Five years later, in 1984.

Parenti: You’ve talked about adjusting to Cuba, but could you talk a bit about adjusting to exile.

Shakur: Well, for me exile means separation from people I love. I didn’t, and don’t miss the U.S., per se. But black culture, black life in the U.S., that African American flavor, I definitely miss. The language, the movements, the style, I get nostalgic about that. Adjusting to exile is coming to grips with the fact that you may never go back to where you come from. The way I dealt with that, psychologically, was thinking about slavery. You know, a slave had to come to grips with the fact that “I may never see Africa again.” Then a maroon, a runaway slave, has to–even in the act of freedom–adjust to the fact that being free or struggling for freedom means, “I’ll be separated from people I love.” So I drew on that and people like Harriet Tubman and all those people who got away from slavery. Because, that’s what prison looked like. It looked like slavery. It felt like slavery. It was black people and people of color in chains. And the way I got there was slavery. If you stand up and say “I don’t go for the status quo.” Then “we got something for you, it’s a whip, a chain, a cell.” Even in being free it was like, “I am free but now what?” There was a lot to get used to. Living in a society committed to social justice, a Third World country with a lot of problems. It took a while to understand all that Cubans are up against and fully appreciate all they are trying to do.

Parenti: Did the Africanness of Cuba help, did that provide solace?

Shakur: The first thing that was comforting was the politics. It was such a relief. You know, in the States you feel overwhelmed by the negative messages that you get and you feel weird, like you’re the only one seeing all this pain and inequality. People are saying, “Forget about that, just try to get rich, dog eat dog, get your own, buy, spend, consume.” So living here was an affirmation of myself, it was like “Okay, there are lots of people who get outraged at injustice.” The African culture I discovered later. At first I was learning the politics, about socialism–what it feels like to live in a country where everything is owned by the people, where health care and medicine are free. Then I started to learn about the Afro-Cuban religions, the Santaria, Palo Monte, the Abakua. I wanted to understand the ceremonies and the philosophy. I really came to grips with how much we–black people in the U.S.–were robbed of. Here, they still know rituals preserved from slavery times. It was like finding another piece of myself. I had to find an African name. I’m still looking for pieces of that Africa I was torn from. I’ve found it here in all aspects of the culture. There is a tendency to reduce the Africanness of Cuba to the Santaria. But it’s in the literature, the language, the politics.

Parenti: When the USSR collapsed, did you worry about a counter-revolution in Cuba, and by extension, your own safety?

Shakur: Of course, I would have to have been nuts not to worry. People would come down here from the States and say, “How long do you think the revolution has–two months, three months? Do you think the revolution will survive? You better get out of here.” It was rough. Cubans were complaining every day, which is totally sane. I mean, who wouldn’t? The food situation was really bad, much worse than now, no transportation, eight-hour blackouts. We would sit in the dark and wonder, “How much can people take?” I’ve been to prison and lived in the States, so I can take damn near anything. I felt I could survive whatever–anything except U.S. imperialism coming in and taking control. That’s the one thing I couldn’t survive. Luckily, a lot of Cubans felt the same way. It took a lot for people to pull through, waiting hours for the bus before work. It wasn’t easy. But this isn’t a superficial, imposed revolution. This is one of those gut revolutions. One of those blood, sweat and tears revolutions. This is one of those revolutions where people are like, “We ain’t going back onto the plantation, period. We don’t care if you’re Uncle Sam, we don’t care about your guided missiles, about your filthy, dirty CIA maneuvers. We’re this island of 11 million people and we’re gonna live the way we want and if you don’t like it, go take a ride.” Of course, not everyone feels like that, but enough do.

Parenti: What about race and racism in Cuba?

Shakur: That’s a big question. The revolution has only been around thirty-something years. It would be fantasy to believe that the Cubans could have completely gotten rid of racism in that short a time. Socialism is not a magic wand: wave it and everything changes.

Parenti: Can you be more specific about the successes and failures along these lines?

Shakur: I can’t think of any area of the country that is segregated. Another example, the Third Congress of the Cuban Communist Party was focused on making party leadership reflect the actual number of people of color and women in the country. Unfortunately by the time the Fourth Congress rolled around the whole focus had to be on the survival of the revolution. When the Soviet Union and the socialist camp collapsed, Cuba lost something like 8.5% of its income. It’s a process, but I honestly think that there’s room for a lot of changes throughout the culture. Some people still talk about “good hair” and “bad hair.” Some people think light skin is good, that if you marry a light person you’re advancing the race. There are a lot of contradictions in people’s consciousness. There still needs to be de-eurocentrizing in the schools, though Cuba is further along with that than most places in the world, In fairness, I think that race relations in Cuba are twenty times better than they are in the States, and I believe the revolution is committed to eliminating racism completely. I also feel that tine special period has changed conditions in Cuba. It’s brought in lots of white tourists, many of whom are racists and expect to be waited on subserviently. Another thing is the joint venture corporations which bring their racist ideas and racist corporate practices, for example not hiring enough blacks. Ali of that means the revolution has to be more vigilant than ever in identifying and dealing with racism.

Parenti: A charge one hears, even on the left, is that institutional racism still exists in Cuba. Is that true? Does one find racist patterns in allocation o/housing, work, or the functions of criminal justice?

Shakur: No. I don’t think institutional racism, as such, exists in Cuba. But at the same time, people have their personal prejudices. Obviously these people, with these personal prejudices, must work somewhere, and must have some influence on the institutions they work in. But I think it’s superficial to say racism is institutionalized in Cuba. I believe that there needs to be a constant campaign to educate people, sensitize people, and analyze racism. The fight against racism always has two levels; the level of politics and policy but also the level tof individual consciousness. One of the things that influences ideas about race in Cuba is that the revolution happened in 1959, when the world had a very limited understanding of what racism was. During the 1960s, the world saw the black power movement, which I, for one, very much benefited from. You know “black is beautiful,” exploring African art, literature, and culture. That process didn’t really happen in Cubar. Over the years, the revolution accomplished so much that most people thought that meant the end of racism. For example, I’d say that more than 90% of black people with college degrees were able to do so because of the revolution. They were in a different historical place. The emphasis, for very good reasons, was on black-white unity and the survival of the revolution. So it’s only now that people in the universities are looking into the politics of identity.

Parenti: Are you still a revolutionary?

Shakur: I am still a revolutionary, because I believe that in the United States there needs to be a complete and profound change in the system of so-called democracy. It’s really a “dollarocracy.” Which millionaire is going to get elected? Can you imagine if you went to a restaurant and the only thing on the menu was dried turd or dead fungus. That’s not appetizing. I feel the same way about the political spectrum in the U.S. What exists now has got to go. All of it: how wealth is distributed, how the environment is treated. If you let these crazy politicians keep ruling, the planet will be destroyed.

Parenti: In the 1960s, organizations you worked with advocated armed self-defense. How do you think social change can best be achieved in the States today?

Shakur: I still believe in self-defense and self-determination for Africans and other oppressed people in America. I believe in peace, but I think it’s totally immoral to brutalize and oppress people, to commit genocide against people, and then tell them they don’t have the right to free themselves in whatever way they deem necessary. But right now the most important thing is consciousness raising. Making social change and social justice means people have to be more conscious across the board, inside and outside the movement, not only around race, but around class, sexism, the ecology, whatever. The methods of 1917, standing on a comer with leaflets, standing next to someone saying “Workers of the world unite” won’t work. We need to use alternative means of communication. The old ways of attaining consciousness aren’t going to work. The little Leninist study groups won’t do it. We need to use video, audio, the Internet. We also need to work on the basics of rebuilding community. How are you going to organized or liberate your community if you don’t have one? I live in Cuba, right? We get U.S. movies here, and I am sick of the monsters; it’s the tyranny of the monsters. Every other movie is fear and monsters. They’ve even got monster babies. People are expected to live in this world of alienation and tear. I hear that in the States people are even afraid to make eye contact in the streets. No social change can happen if people are that isolated. So we need to rebuild a sense of community and that means knocking on doors and reconnecting.

https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/israel-postwar-gaza-plan-palestine-bf36d1c9

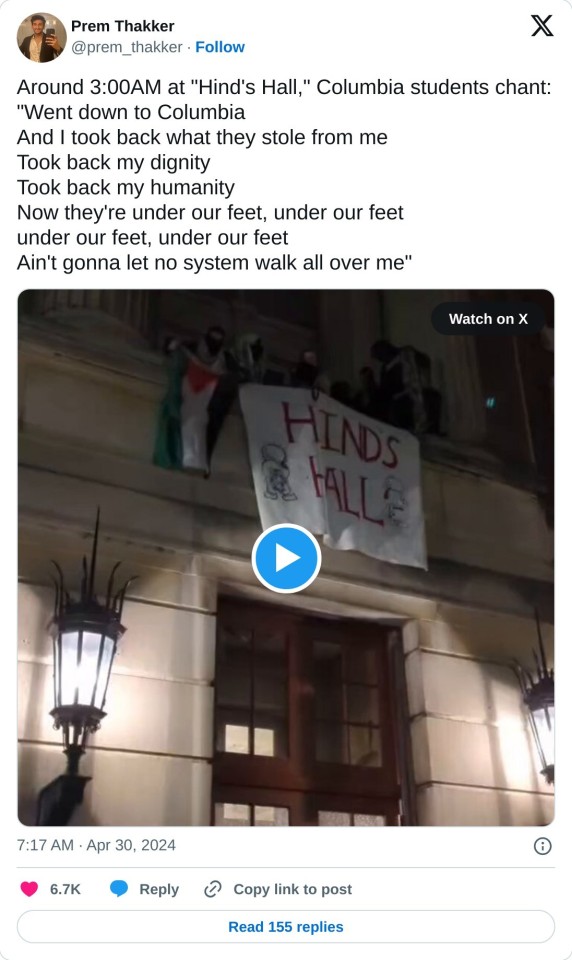

Hind Rajab was a 5 year old girl in Gaza who was killed while she hid alone in a car, along with the paramedics who tried to rescue her. Yesterday students at Columbia seized the administration building and renamed it in her honor.

Gadzooks Bazooka Instagram: gadzooks_bazooka

Remembering #HindRajab & children in #Gaza: This is what the mother of the child, Hind Rajab . https://tmblr.co/ZTeZMyfB_GHeeu00

DrSonnet — هذا ما قالته والدة الطفلة هند رجب عندما سمعت بخبر... (tumblr.com)

you cant reclaim slurs that arent yours. if you get called the sand n-slur or prarie n-slur you CANNOT reclaim the n-slur. like. period. i dont know why this is so difficult to comprehend

One thing I would really like to see socialists abandon is the line on capitalism (the system of social production) | the bourgeoisie (the class) | liberalism (the ideological structure) being a “progressive” force, in a positive sense of that term. I recall a pretty irritating conversation with a right-libertarian who asked me “how can capitalism be exploitation, according to Marx, when it’s raised living standards around the globe?”

Now, I think there’s a lot of ways to respond to that:

1) calling the claim itself into doubt statistically [most of the recent trend in poverty downturn is just China urbanizing; many other places are stagnating if not getting worse]. 2) calling the claim into doubt historically [does the boost in living standards for China and the Soviet Union, from urbanization and industrialization, mean that “actually existing socialism” is immune to critique? I would hope not.] 3) noting that exploitation as Marx used it was primarily a technical and non-moral term [his fundamental ethical worry, as I have argued elsewhere, was domination]. 4) digging into the weeds of the theory of exploitation to show that an increased standard of living and increased exploitation (as Marx understood that term) are not mutually exclusive, on his exact terms.

But the most common one is to concede that yes, capitalist mechanisms have massively expanded the powers of the human body. This is, after all, part of Marx’s interest in capitalism in the first place, its “revolutionizing” powers and ability to break down barriers to expansion or absorb preexisting practices and patterns into its mechanisms. So there’s this sense in which ground is ceded to the liberal view of history as progress, in which capitalism is superior by some metric(s) when compared to other modes of production. Communists are therefore in the position of having to assert that in spite of this, capitalism should still be abolished.

But I think that’s not actually ground that it’s necessary to concede, at least not in any meaningful sense.

I think there are a few good reasons for giving up this claim. One is that it’s in many ways not true, and we should throw out the Whig historiography and stagist theorizing that has seeped into socialist thought and action by way of The German Ideology and other underdeveloped sources. For instance, the bourgeoisie as a class had to be dragged kicking and screaming into revolution by subaltern forces. Although many of the “bourgeois revolutions” unfolded or “resolved” in accordance with bourgeois desires and interests, they were not motivated by them. The bourgeoisie, no matter where they are, are pretty reliably conservative in their general disposition.

Another is that “progress” should not be a communist virtue or metric by which to judge the world; it is rooted in a thoroughly liberal philosophy of history. As Marx says - and didn’t always express adequately - “it is far too easy to be liberal at the expense of the Middle Ages.” I imagine that I would not like to live in a feudal, despotic, or tributary society - this much should be obvious. But the notion that capitalism is therefore superior, more tolerable, because its central form of domination is impersonal (setting aside, for the moment, all the forms of unfreedom and interpersonal domination that capitalism relies upon, which fall particularly hard upon certain demographics and geographical areas), doesn’t follow from that. There’s nothing noble about the fact that capitalists seized upon destruction and dispossession unleashed by the feudal state. Primitive accumulation - whether viewed as a historical juncture or an ongoing process vital to capitalism to this day - is not a redemptive force. Yes, capitalism managed to expand the powers of the body - at the expense of many.

For me the question is not “is capitalism better than the social forms it replaced?”, because I don’t think that question is either particularly helpful or terribly interesting. It’s as silly as asking if feudalism is better than a slave society - partly because it presumes this linear, stagist narrative of history that is false, and partly because it asks us to pick between horrors. Rather, the question is, “was all the suffering worth it?” And for me the answer is no.

Could we have gotten something better? Can we still?

-

hudagaza reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

hudagaza reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

remade-man reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

remade-man reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

holy-leaves reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

holy-leaves reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

rob-os-17 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

rob-os-17 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

jeff500 liked this · 3 weeks ago

jeff500 liked this · 3 weeks ago -

feyrehermione reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

feyrehermione reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

spookyteeth liked this · 3 weeks ago

spookyteeth liked this · 3 weeks ago -

andromeda1aura liked this · 4 weeks ago

andromeda1aura liked this · 4 weeks ago -

googaszabloing liked this · 4 weeks ago

googaszabloing liked this · 4 weeks ago -

innerpostgraduate liked this · 1 month ago

innerpostgraduate liked this · 1 month ago -

dirtyoldheathenagain liked this · 1 month ago

dirtyoldheathenagain liked this · 1 month ago -

cre4tureonp4wz liked this · 1 month ago

cre4tureonp4wz liked this · 1 month ago -

catlizard liked this · 1 month ago

catlizard liked this · 1 month ago -

deepesttravelerpoetry liked this · 1 month ago

deepesttravelerpoetry liked this · 1 month ago -

blackpointgame liked this · 1 month ago

blackpointgame liked this · 1 month ago -

loversveil reblogged this · 1 month ago

loversveil reblogged this · 1 month ago -

your-watcher reblogged this · 1 month ago

your-watcher reblogged this · 1 month ago -

your-watcher liked this · 1 month ago

your-watcher liked this · 1 month ago -

optimistic-autistic liked this · 1 month ago

optimistic-autistic liked this · 1 month ago -

1ts0kn0tt0be0k reblogged this · 1 month ago

1ts0kn0tt0be0k reblogged this · 1 month ago -

thebisexualwreckoning reblogged this · 1 month ago

thebisexualwreckoning reblogged this · 1 month ago -

urlocal-degenerate liked this · 1 month ago

urlocal-degenerate liked this · 1 month ago -

tangledtheseriesfan liked this · 1 month ago

tangledtheseriesfan liked this · 1 month ago -

redthreads liked this · 1 month ago

redthreads liked this · 1 month ago -

zoebelle9 reblogged this · 1 month ago

zoebelle9 reblogged this · 1 month ago -

zoebelle9 liked this · 1 month ago

zoebelle9 liked this · 1 month ago -

deathlyfandoms reblogged this · 1 month ago

deathlyfandoms reblogged this · 1 month ago -

juju-fisher liked this · 2 months ago

juju-fisher liked this · 2 months ago -

merpdaberp liked this · 2 months ago

merpdaberp liked this · 2 months ago -

addictedtoyourcrush liked this · 2 months ago

addictedtoyourcrush liked this · 2 months ago -

wall-artist2 liked this · 2 months ago

wall-artist2 liked this · 2 months ago -

specss00 liked this · 2 months ago

specss00 liked this · 2 months ago -

every-dayiwakeup liked this · 2 months ago

every-dayiwakeup liked this · 2 months ago -

just-to-observe reblogged this · 2 months ago

just-to-observe reblogged this · 2 months ago -

just-to-observe liked this · 2 months ago

just-to-observe liked this · 2 months ago -

finthehuman42 liked this · 2 months ago

finthehuman42 liked this · 2 months ago -

indigoisaspookyghost2 liked this · 2 months ago

indigoisaspookyghost2 liked this · 2 months ago -

wonderful3261 liked this · 2 months ago

wonderful3261 liked this · 2 months ago -

kind-words-like-honey liked this · 2 months ago

kind-words-like-honey liked this · 2 months ago -

dvdautoart reblogged this · 2 months ago

dvdautoart reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sollamaface68 liked this · 2 months ago

sollamaface68 liked this · 2 months ago -

ellohelloo reblogged this · 2 months ago

ellohelloo reblogged this · 2 months ago -

daminette-56 liked this · 2 months ago

daminette-56 liked this · 2 months ago