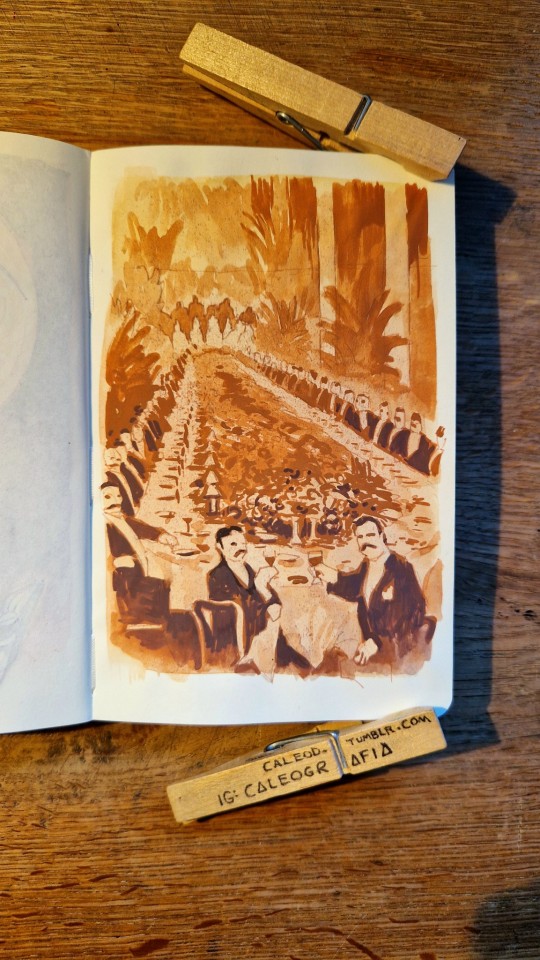

Hello! I Saw Your Kimono Drawing Guide, And I Have Some Questions. I Saw This Art And Was Wondering About

Hello! i saw your kimono drawing guide, and i have some questions. I saw this art and was wondering about a few things: what is the tied knot& tassel things on the sleeves for? and, what hairstyle is the lady wearing? If you know, please tell me! If you don't know, could it be possible to direct me to someone that might? Thank you for taking the time to answer, if you're able! Have a lovely night/day!

Hi and thank you for your question :) The ukiyoe you are sharing is by Utagawa Kunisada and titled Genji rokujo no hana (源氏六條の花), or "Cherry Blossoms at Genji's Rokujô Mansion". It is part of a three prints set:

It depicts an imaginary scenery from The tale of Genji, and the young lady playing with her pet cat is the princess Onna San no Miya.

Characters are not shown wearing period accurate clothes (from Heian era), but luscious Edo period attires. Because of her rank, the young princess is wearing what Edo princesses would, especially the trademark hairstyle named fukiya 吹輪.

You'll find below a translation from a costume photobook I did a while ago. Note the big bridge style front hairpin, and the drum like one in the back. Princesses from the buke (samurai class) would also have dangling locks called aikyôge (I also found the term okurege), but I am not sure kuge princesses (noble class) wore them too.

There is a whole dispute about this hairstyle, as we are not actually sure it was worn as such by actual princesses. This style may have in fact started as a somehow cliché bunraku/kabuki costume used to depict princesses (think a bit like Western Cinderella-types princess gowns). Nowadays, it is found only as a theater style, or worn by Maiko during Setsubun season.

For comparison, here is character Shizuka Gozen from kabuki play Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura:

As for the dangling cords, I covered those in a past ask about kamuro that you can find here (part 1 / part 2). TL:DR: I am still not sure what is the exact name for those decorations (kazari himo? sode no himo?).

But their use is pretty much linked to 3 things:

1) luck + protection (knots have auspicous meanings),

2) reinforcing weak points of garnment (here: sleeves wrist opening)

3) cuteness impact, as much like furisode (long sleeves kimono) those dangling ribbons were mostly seen on girls/young unmarried ladies by the Edo period

All the design elements chosen by Utagawa Kunisada for his Onna San no Miya stress own young and carefree she is still (which considering her narrative arc is in fact a bit sad... like all Genji Monogatari stories). BUT: bonus points for pet cat!

Hope that helps :)

More Posts from Misscounterfactual and Others

GUYS!!!!! IT'S GOING TO LAUNCH IN FIVE MINUTES!!!

I'M BEING SERIOUS

NASA Inspires Your Crafty Creations for World Embroidery Day

It’s amazing what you can do with a little needle and thread! For #WorldEmbroideryDay, we asked what NASA imagery inspired you. You responded with a variety of embroidered creations, highlighting our different areas of study.

Here’s what we found:

Webb’s Carina Nebula

Wendy Edwards, a project coordinator with Earth Science Data Systems at NASA, created this embroidered piece inspired by Webb’s Carina Nebula image. Captured in infrared light, this image revealed for the first time previously invisible areas of star birth. Credit: Wendy Edwards, NASA. Pattern credit: Clare Bray, Climbing Goat Designs

Wendy Edwards, a project coordinator with Earth Science Data Systems at NASA, first learned cross stitch in middle school where she had to pick rotating electives and cross stitch/embroidery was one of the options. “When I look up to the stars and think about how incredibly, incomprehensibly big it is out there in the universe, I’m reminded that the universe isn’t ‘out there’ at all. We’re in it,” she said. Her latest piece focused on Webb’s image release of the Carina Nebula. The image showcased the telescope’s ability to peer through cosmic dust, shedding new light on how stars form.

Ocean Color Imagery: Exploring the North Caspian Sea

Danielle Currie of Satellite Stitches created a piece inspired by the Caspian Sea, taken by NASA’s ocean color satellites. Credit: Danielle Currie/Satellite Stitches

Danielle Currie is an environmental professional who resides in New Brunswick, Canada. She began embroidering at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic as a hobby to take her mind off the stress of the unknown. Danielle’s piece is titled “46.69, 50.43,” named after the coordinates of the area of the northern Caspian Sea captured by LandSat8 in 2019.

An image of the Caspian Sea captured by Landsat 8 in 2019. Credit: NASA

Two Hubble Images of the Pillars of Creation, 1995 and 2015

Melissa Cole of Star Stuff Stitching created an embroidery piece based on the Hubble image Pillars of Creation released in 1995. Credit: Melissa Cole, Star Stuff Stitching

Melissa Cole is an award-winning fiber artist from Philadelphia, PA, USA, inspired by the beauty and vastness of the universe. They began creating their own cross stitch patterns at 14, while living with their grandparents in rural Michigan, using colored pencils and graph paper. The Pillars of Creation (Eagle Nebula, M16), released by the Hubble Telescope in 1995 when Melissa was just 11 years old, captured the imagination of a young person in a rural, religious setting, with limited access to science education.

Lauren Wright Vartanian of the shop Neurons and Nebulas created this piece inspired by the Hubble Space Telescope’s 2015 25th anniversary re-capture of the Pillars of Creation. Credit: Lauren Wright Vartanian, Neurons and Nebulas

Lauren Wright Vartanian of Guelph, Ontario Canada considers herself a huge space nerd. She’s a multidisciplinary artist who took up hand sewing after the birth of her daughter. She’s currently working on the illustrations for a science themed alphabet book, made entirely out of textile art. It is being published by Firefly Books and comes out in the fall of 2024. Lauren said she was enamored by the original Pillars image released by Hubble in 1995. When Hubble released a higher resolution capture in 2015, she fell in love even further! This is her tribute to those well-known images.

James Webb Telescope Captures Pillars of Creation

Darci Lenker of Darci Lenker Art, created a rectangular version of Webb’s Pillars of Creation. Credit: Darci Lenker of Darci Lenker Art

Darci Lenker of Norman, Oklahoma started embroidery in college more than 20 years ago, but mainly only used it as an embellishment for her other fiber works. In 2015, she started a daily embroidery project where she planned to do one one-inch circle of embroidery every day for a year. She did a collection of miniature thread painted galaxies and nebulas for Science Museum Oklahoma in 2019. Lenker said she had previously embroidered the Hubble Telescope’s image of Pillars of Creation and was excited to see the new Webb Telescope image of the same thing. Lenker could not wait to stitch the same piece with bolder, more vivid colors.

Milky Way

Darci Lenker of Darci Lenker Art was inspired by NASA’s imaging of the Milky Way Galaxy. Credit: Darci Lenker

In this piece, Lenker became inspired by the Milky Way Galaxy, which is organized into spiral arms of giant stars that illuminate interstellar gas and dust. The Sun is in a finger called the Orion Spur.

The Cosmic Microwave Background

This image shows an embroidery design based on the cosmic microwave background, created by Jessica Campbell, who runs Astrostitches. Inside a tan wooden frame, a colorful oval is stitched onto a black background in shades of blue, green, yellow, and a little bit of red. Credit: Jessica Campbell/ Astrostitches

Jessica Campbell obtained her PhD in astrophysics from the University of Toronto studying interstellar dust and magnetic fields in the Milky Way Galaxy. Jessica promptly taught herself how to cross-stitch in March 2020 and has since enjoyed turning astronomical observations into realistic cross-stitches. Her piece was inspired by the cosmic microwave background, which displays the oldest light in the universe.

The full-sky image of the temperature fluctuations (shown as color differences) in the cosmic microwave background, made from nine years of WMAP observations. These are the seeds of galaxies, from a time when the universe was under 400,000 years old. Credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team

GISSTEMP: NASA’s Yearly Temperature Release

Katy Mersmann, a NASA social media specialist, created this embroidered piece based on NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) global annual temperature record. Earth’s average surface temperature in 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest year on record. Credit: Katy Mersmann, NASA

Katy Mersmann is a social media specialist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. She started embroidering when she was in graduate school. Many of her pieces are inspired by her work as a communicator. With climate data in particular, she was inspired by the researchers who are doing the work to understand how the planet is changing. The GISTEMP piece above is based on a data visualization of 2020 global temperature anomalies, still currently tied for the warmest year on record.

In addition to embroidery, NASA continues to inspire art in all forms. Check out other creative takes with Landsat Crafts and the James Webb Space telescope public art gallery.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

20-12-22

I’m still crying over the beauty that was the Sony Reader. Cell service, stylus, dictionary, touchscreen, audio and came in a robust case.

Amazon killed E-ink innovation. But it's back.

Amazon killed E-ink innovation. But it’s back.

View On WordPress

Now Live: Artemis I launch with Astronaut Kayla Barron.

Through Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term lunar presence and serving as a steppingstone to send astronauts to Mars.

source

Rockets, Racecars, and the Physics of Going Fast

When our Space Launch System (SLS) rocket launches the Artemis missions to the Moon, it can have a top speed of more than six miles per second. Rockets and racecars are designed with speed in mind to accomplish their missions—but there’s more to speed than just engines and fuel. Learn more about the physics of going fast:

Take a look under the hood, so to speak, of our SLS mega Moon rocket and you’ll find that each of its four RS-25 engines have high-pressure turbopumps that generate a combined 94,400 horsepower per engine. All that horsepower creates more than 2 million pounds of thrust to help launch our four Artemis astronauts inside the Orion spacecraft beyond Earth orbit and onward to the Moon. How does that horsepower compare to a racecar? World champion racecars can generate more than 1,000 horsepower as they speed around the track.

As these vehicles start their engines, a series of special machinery is moving and grooving inside those engines. Turbo engines in racecars work at up to 15,000 rotations per minute, aka rpm. The turbopumps on the RS-25 engines rotate at a staggering 37,000 rpm. SLS’s RS-25 engines will burn for approximately eight minutes, while racecar engines generally run for 1 ½-3 hours during a race.

To use that power effectively, both rockets and racecars are designed to slice through the air as efficiently as possible.

While rockets want to eliminate as much drag as possible, racecars carefully use the air they’re slicing through to keep them pinned to the track and speed around corners faster. This phenomenon is called downforce.

Steering these mighty machines is a delicate process that involves complex mechanics.

Most racecars use a rack-and-pinion system to convert the turn of a steering wheel to precisely point the front tires in the right direction. While SLS doesn’t have a steering wheel, its powerful engines and solid rocket boosters do have nozzles that gimbal, or move, to better direct the force of the thrust during launch and flight.

Racecar drivers and astronauts are laser focused, keeping their sights set on the destination. Pit crews and launch control teams both analyze data from numerous sensors and computers to guide them to the finish line. In the case of our mighty SLS rocket, its 212-foot-tall core stage has nearly 1,000 sensors to help fly, track, and guide the rocket on the right trajectory and at the right speed. That same data is relayed to launch teams on the ground in real time. Like SLS, world-champion racecars use hundreds of sensors to help drivers and teams manage the race and perform at peak levels.

Knowing how to best use, manage, and battle the physics of going fast, is critical in that final lap. You can learn more about rockets and racecars here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Delicate patterns evocative of ancient palaces for this outfit, pairing a kimono with decorated kaiawase (Heian period shell-matching game) over waves ground, and a beautiful obi depicting tagasode (kimono discarded on ikou/rack)

Adobe steals your color

When a company breaks a product you rely on — wrecking decades of work — it’s natural to feel fury. Companies know this, so they try to deflect your rage by blaming their suppliers. Sometimes, it’s suppliers who are at fault — but other times, there is plenty of blame to go around.

For example, when Apple deleted all the working VPNs from its Chinese App Store and backdoored its Chinese cloud servers, it blamed the Chinese government. But the Chinese state knew that Apple had locked its devices so that its Chinese customers couldn’t install third-party apps.

That meant that an order to remove working VPNs and apps that used offshore clouds from the App Store would lock Apple customers into Chinese state surveillance. The order to block privacy tools was a completely foreseeable consequence of Apple’s locked-down “ecosystem.”

https://locusmag.com/2021/01/cory-doctorow-neofeudalism-and-the-digital-manor/

In 2013, Adobe started to shift its customers to the cloud, replacing apps like Photoshop and Illustrator with “Software as a Service” (“SaaS”) versions that you would have to pay rent on, every month, month after month, forever. It’s not hard to understand why this was an attractive proposition for Adobe!

Adobe, of course, billed its SaaS system as good for its customers — rather than paying thousands of dollars for its software up front, you could pay a few dollars (anywhere from $10-$50) every month instead. Eventually, of course, you’d end up paying more, assuming these were your professional tools, which you expected to use for the rest of your life.

For people who work in prepress, a key part of their Adobe tools is integration with Pantone. Pantone is a system for specifying color-matching. A Pantone number corresponds to a specific tint that’s either made by mixing the four standard print colors (cyan, magenta, yellow and black, AKA “CMYK”), or by applying a “spot” color. Spot colors are added to print jobs after the normal CMYK passes — if you want a stripe of metallic gold or a blob of hot pink, you specify its Pantone number and the printer loads up a separate ink and runs your media through its printer one more time.

Pantone wants to license this system out, so it needs some kind of copyrightable element. There aren’t many of these in the Pantone system! There’s the trademark, but that’s a very thin barrier. Trademark has a broad “nominative use” exception: it’s not a trademark violation to say, “Pantone 448C corresponds to the hex color #4a412a.”

Perhaps there’s a copyright? Well yes, there’s a “thin” database copyright on the Pantone values and their ink equivalents. Anyone selling a RIP or printer that translates Pantone numbers to inks almost certainly has to license Pantone’s copyright there. And if you wanted to make an image-editing program that conveyed the ink data to a printer, you’d best take a license.

All of this is suddenly relevant because it appears that things have broken down between Adobe and Pantone. Rather than getting Pantone support bundled in with your Adobe apps, you must now pay $21/month for a Pantone plugin.

https://twitter.com/funwithstuff/status/1585850262656143360

Remember, Adobe’s apps have moved to the cloud. Any change that Adobe makes in its central servers ripples out to every Adobe user in the world instantaneously. If Adobe makes a change to its apps that you don’t like, you can’t just run an older version. SaaS vendors like to boast that with cloud-based apps, “you’re always running the latest version!”

The next version of Adobe’s apps will require you to pay that $21/month Pantone fee, or any Pantone-defined colors in your images will render as black. That’s true whether you created the file last week or 20 years ago.

Doubtless, Adobe will blame Pantone for this, and it’s true that Pantone’s greed is the root cause here. But this is an utterly foreseeable result of Adobe’s SaaS strategy. If Adobe’s customers were all running their apps locally, a move like this on Pantone’s part would simply cause every affected customer to run older versions of Adobe apps. Adobe wouldn’t be able to sell any upgrades and Pantone wouldn’t get any license fees.

But because Adobe is in the cloud, its customers don’t have that option. Adobe doesn’t have to have its users’ backs because if it caves to Pantone, users will still have to rent its software every month, and because that is the “latest version,” those users will also have to rent the Pantone plugin every month — forever.

What’s more, while there may not be any licensable copyright in a file that simply says, “Color this pixel with Pantone 448C” (provided the program doesn’t contain ink-mix descriptions), Adobe’s other products — its RIPs and Postscript engines — do depend on licensable elements of Pantone, so the company can’t afford to tell Pantone to go pound sand.

Like the Chinese government coming after Apple because they knew that any change that Apple made to its service would override its customers’ choices, Pantone came after Adobe because they knew that SaaS insulated Adobe from its customers’ wrath.

Adobe customers can’t even switch to its main rival, Figma. Adobe’s just dropped $20b to acquire that company and ensure that its customers can’t punish it for selling out by changing vendors.

Pantone started out as a tech company: a way to reliably specify ink mixes in different prepress houses and print shops. Today, it’s an “IP” company, where “IP” means “any law or policy that allows me to control the conduct of my customers, critics or competitors.”

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

That’s likewise true of Adobe. The move to SaaS is best understood as a means to exert control over Adobe’s customers and competitors. Combined with anti-competitive killer acquisitions that gobble up any rival that manages to escape this control, and you have a hostage situation that other IP companies like Pantone can exploit.

A decade or so ago, Ginger Coons created Open Colour Standard, an attempt to make an interoperable alternative to Pantone. Alas, it seems dormant today:

http://adaptstudio.ca/ocs/

Owning colors is a terrible idea and technically, it’s not possible to do so. Neither UPS Brown nor John Deere Green are “owned” in any meaningful sense, but the companies certainly want you to believe that they are. Inspired by them and Pantone, people with IP brain-worms keep trying to turn colors into property:

https://onezero.medium.com/crypto-copyright-bdf24f48bf99

The law is clear that colors aren’t property, but by combining SaaS, copyright, trademark, and other tech and policies, it is becoming increasingly likely that some corporation will stealing the colors out from under our very eyes.

[Image ID: A Pantone swatchbook; it slowly fades to grey, then to black.]

-

gotteso-0-o liked this · 4 months ago

gotteso-0-o liked this · 4 months ago -

lareinefan liked this · 5 months ago

lareinefan liked this · 5 months ago -

alpen-veil-chen reblogged this · 5 months ago

alpen-veil-chen reblogged this · 5 months ago -

charlotteyeo liked this · 6 months ago

charlotteyeo liked this · 6 months ago -

cool-kats-of-the-disco liked this · 7 months ago

cool-kats-of-the-disco liked this · 7 months ago -

dwaigoniii liked this · 8 months ago

dwaigoniii liked this · 8 months ago -

ichiyu liked this · 8 months ago

ichiyu liked this · 8 months ago -

epimeomeo liked this · 9 months ago

epimeomeo liked this · 9 months ago -

finalmoss liked this · 9 months ago

finalmoss liked this · 9 months ago -

tadoku liked this · 10 months ago

tadoku liked this · 10 months ago -

brambleberrybush liked this · 10 months ago

brambleberrybush liked this · 10 months ago -

yenoodlethings liked this · 1 year ago

yenoodlethings liked this · 1 year ago -

cafeselection reblogged this · 1 year ago

cafeselection reblogged this · 1 year ago -

castgil-cmd reblogged this · 1 year ago

castgil-cmd reblogged this · 1 year ago -

hanzeebuns liked this · 1 year ago

hanzeebuns liked this · 1 year ago -

trotskyrosedreamer liked this · 1 year ago

trotskyrosedreamer liked this · 1 year ago -

mikhailmiakoda liked this · 1 year ago

mikhailmiakoda liked this · 1 year ago -

lesmodesdecrawley liked this · 1 year ago

lesmodesdecrawley liked this · 1 year ago -

miserable-homo-momo liked this · 1 year ago

miserable-homo-momo liked this · 1 year ago -

lulumarill liked this · 1 year ago

lulumarill liked this · 1 year ago -

nicolas-lovelace liked this · 1 year ago

nicolas-lovelace liked this · 1 year ago -

fucking-comedy liked this · 1 year ago

fucking-comedy liked this · 1 year ago -

artemistevius liked this · 1 year ago

artemistevius liked this · 1 year ago -

dahlias-love reblogged this · 1 year ago

dahlias-love reblogged this · 1 year ago -

many-small-mangoes liked this · 1 year ago

many-small-mangoes liked this · 1 year ago -

sekkori reblogged this · 1 year ago

sekkori reblogged this · 1 year ago -

yg-calroniscanon liked this · 1 year ago

yg-calroniscanon liked this · 1 year ago -

queenofmattelipsticks reblogged this · 1 year ago

queenofmattelipsticks reblogged this · 1 year ago -

queenofmattelipsticks liked this · 1 year ago

queenofmattelipsticks liked this · 1 year ago -

lamoorgalore liked this · 1 year ago

lamoorgalore liked this · 1 year ago -

chibigrimmreaper reblogged this · 1 year ago

chibigrimmreaper reblogged this · 1 year ago -

purposefulcryptic liked this · 1 year ago

purposefulcryptic liked this · 1 year ago -

mybookof-you reblogged this · 1 year ago

mybookof-you reblogged this · 1 year ago -

ai56 liked this · 1 year ago

ai56 liked this · 1 year ago -

thegreatandgrandarchives reblogged this · 1 year ago

thegreatandgrandarchives reblogged this · 1 year ago -

narcoticwriter liked this · 1 year ago

narcoticwriter liked this · 1 year ago -

dkniade reblogged this · 1 year ago

dkniade reblogged this · 1 year ago -

dkniade liked this · 1 year ago

dkniade liked this · 1 year ago -

cloudedflowers liked this · 1 year ago

cloudedflowers liked this · 1 year ago -

hakodatemonamour reblogged this · 1 year ago

hakodatemonamour reblogged this · 1 year ago -

kanotototori liked this · 1 year ago

kanotototori liked this · 1 year ago -

rosyflowerfields liked this · 1 year ago

rosyflowerfields liked this · 1 year ago -

asketchysomebody liked this · 1 year ago

asketchysomebody liked this · 1 year ago -

empresstress13 reblogged this · 1 year ago

empresstress13 reblogged this · 1 year ago