Stuff I’ve Learned About Writing After 10 Weeks In An MFA Program

stuff i’ve learned about writing after 10 weeks in an MFA program

so as some of you might know, i’m currently going to grad school for writing fiction and creative nonfiction. it’s a well-respected program, fully funded, with fantastic faculty and excellent classes. i’m learning a lot, so i thought even though i’m only just getting started (it’s a 2-year program), i’d share some stuff i’ve learned.

all writing is valid. scribbling a poem onto a cocktail napkin at an awkward family function is just as worthy of careful literary analysis as Faulkner. i’ve read stories and thought this is the worst thing i’ve ever read, i can’t take this seriously and then watched as established, widely published authors and academics provided a thoughtful and thorough criticism of it. treat all writing with respect, your own included.

all research is valid. i went on a rant about BDSM politics in queer culture, and this boy, who looked totally bewildered, asked me what BDSM was. after (hopefully) tactfully explaining it to him, he asked me, “so is that like…your research or something?” to which i replied, “…you could say that.” what i mean is, anything you are curious about is worthy of your attention and curiosity. anything you want to learn is worth learning. there is no such thing as a guilty pleasure when it comes to education.

good writing is a facet of place. the reason i think we believe our writing and research isn’t valid is because we are writing and researching in spaces that are not conducive to our interests. and when we see ourselves not yielding to those which we compare ourselves, it’s easy to think we’re “bad writers.” the key is to find places (publications, platforms, people, etc) that match your aesthetic, somewhere that your work might belong.

think of it this way: if you go to a function filled with foodies in formal wear talking about their yachts, you’re not going to bring celery sticks with peanut butter and raisins. that doesn’t mean ants on a log are a bad snack, but that this party is the wrong place for it. you bring that snack to a kid’s birthday party where you’ll probably have more fun anyway, and suddenly you’re a five-star chef.

don’t conform. take risks. this is something my workshop leader told me when i was concerned about workshopping my novella, and i told her i wanted to “tone it down.” i have gathered that the people who are considered experts in the field of writing are generally all looking for two things in any given work: creativity and whether or not the piece is doing something. (i’ll comment on the latter in the next point.) creativity is about being weird, about making things that don’t exist yet, using your knowledge of the world and filling in all the gaps with your own design. creativity is not about conforming to anyone else’s standards or expectations.

write to “do something” or create a conversation. admittedly i’m pretty accustomed to writing for the sake of self indulgence, which is great for inspiring first drafts but terrible for everything else. i’ve read works where the purpose of them was the complete romanticization or commentary of the self, and while that’s fine for people who already possess considerable ethos (re: celebrities), for people without it, these works aren’t adding to any conversation on any topic besides that writer’s introspection. (note, this is not “bad writing”; it just has a different place, generally a private journal.)

in the world of fanfic, we are all inherently adding to the conversation of a given canon. without that foundation, in the literary world your canon has to become something else: stories about big picture concepts like grief or oppression; stories subverting a popular generalization; stories that give new light to something. genre is thus not about conformity, but having a creative conversation with people who are interested in the same things you are. writing is about inserting yourself into the dialogue, adding to the lexicon of something greater than yourself.

where this breaks down, however, is the idea that some big picture topics are “overdone” such that they become tropes or cliches. tropes and cliches are indications of conformity. without a cohesive knowledge of your genre or interest to know which gaps need filled, it’s easy to fall into these traps of commonality.

positive and summative feedback is more helpful than negative feedback. a lot of people will disagree with me on this, but generally negative feedback is an indication that you didn’t understand the writers’ vision, and are superimposing your own vision over theirs. most people (in my community anyway) transform their negative criticism into questions for the writer to consider, or point out “what isn’t working.”

that said, the idea of summarizing what you just read is incredibly helpful, because it offers the writer insight into the things you picked up and stuck with you. it aligns the writers’ intentions with the reader’s perceptions to see if a story is working the way it should. this supposes, however, that you have an intention to your story, see: the “do something” point.

and mostly, positive criticism is the literal best. not only does it make writers happy, it encourages them to improve and points out the things they’re doing right so they can polish up what works and sweep away what doesn’t. never be afraid to offer compliments, and if something affected you personally or moved you, let the writer know. the best feedback i’ve given is when i point-blank told the writer, “this piece meant a lot to me, and here’s why.”

write about writing. this is a whole school of thought that i haven’t had time to delve into research-wise, but it’s something i make my students do, and it’s something i’m doing right now just by writing this. reflecting about writing solidifies concepts that you’ve learned so that they become easier to implement in future works. so when you’re done with a piece, write yourself a feedback letter about what you wrote, what you thought worked, and what you can improve for next time. if it’s a fic, maybe this could go in a blog post or an author’s note, or maybe you can just keep it for yourself in a journal. but thinking about writing and writing about writing is an enormously effective tool in development.

i hope this helps someone somewhere. even if it doesn’t, i think this is a good platform for reflection. you can read my other writing advice in my writing advice tag, or see a curation of my advice in my masterpost.

More Posts from Othermanymore and Others

Idnrik-beast (rus. Индрик, derived from old rus. Inorog (Инорог) — “unicorn”) — is a mythological “father of all beasts” from russian legendary. Mentioned in famous Golubinaya (Голубиная) Book (a collection of Eastern-Slavic folk spiritual poems and psalms of the late XV — early XVI century). It is believed that Indrik took form of an enormous creature with a bull’s body, head of a horse and legs of a deer. The can have both one or two horns. Indrik is a master of all groundwaters and underground troves, the protector and king of animals. According to many works of folklore, under certain circumstances Indrik can act as a magical helper of the hero, helping him to find treasure and get rid of the enemies.

“We wanted to create a language that is aesthetically interesting,” says production designer Patrice Vermette. “But it needed to be alien to our civilisation, alien to our technology, alien to everything our mind knows. When Louise first sees the language, you don’t want to give it away to the audience that it’s a language.”

Manhattan Project Glass from Hanford, Washington

This glass was used at the Hanford Washington Manhattan Project location, one of the biggest and most undercover operations the United States military has ever done. It started during WWII in the late 30’s and went on through the cold war era. There were three main facilities around the nation that took part in the making of the first atomic bombs. At Hanford, they created the first plutonium ever to exist, which went into the Trinity bomb in New Mexico, the first man-made nuclear blast, and the plutonium for the Fat Man Bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

This piece is 70% lead with a deep yellow color. It comes on basalt pillar base, cut flat, polished top, core drilled with a LED light set into the stone to illuminate the specimen. The base is 8" in diameter and 34" tall. Approximate weight of display is 200lbs.

Tellurium

Locality:

Faţa Băii (Facebánya; Facebay; Fatiabaja), Zlatna (Zalatna; Zalathna), Alba Co., Romania

Stephan Wolfsried’s Photo

041

I’m all for eldritch angels. Hope mine doesn’t disappoint.

100 Resources to Help You Write Your Novel

The biggest challenge to writing a novel is enduring to the final two words—THE END. Between the first line and the last are questions, choices, doubts. Sometimes they get the better of us, sometimes and we quit before the draft is complete.

The following articles contain insights, inspiration, maps and methods, answers to questions, and myriad tools to get unstuck.

The Idea

Story arises from the impetus that starts the imagination on a quest to create a world in which the idea can grow in a movement toward meaning. Learn how to generate, recognize, and test your story ideas.

The Idea

Where Ideas Come From

Follow the Story

Keeping Confidence When Sails Deflate

What If?

What’s In A Title?

Storm Clouds

Wrong Turn

Obsession

Turn A Taboo

Cerebral Cinema

Heard It Through the Grapevine

Enter Stranger

Mad, Mad World

The Myth of Marital Bliss

A Picture’s Worth 1000 Words

Quotes for Writers

Photo Gallery Prompts

Theme & Premise

Theme is the tangential force that unifies story elements and instills those elements with meaning. From theme, the writer weighs in with a premise, and the story gains its philosophical, psychological, or spiritual spine. A well-crafted premise forces the writer to identify a main character, a central conflict, and a general plot. Like a mini-outline, the premise illuminates the story’s best course.

Understand the dynamics of theme and premise, learn how to differentiate and utilize the two.

Every Story Needs a Theme

Two Sides To Every Story

All-American Theme

How to Write a Story Premise

Plot Structure & Development

Story is a record of years, weeks, days, while plot derives and conveys meaning from a span of years, weeks, days. A hero wants something, goes after it despite opposition, and arrives at a win, lose, or draw. Unlike a chronicle of events (when someone says this happened, then this, then that) plot is dynamic. Plot is an interplay of forces coming together, pushing against each other, incrementally advancing while simultaneously coming to a boil, and ultimately achieving equilibrium.

Discover how to maximize the physics of drama.

The Physics of Drama

Plot Structure in Three Acts

Plot: The Inciting Incident

Plotting Your Novel’s Middle

Plotting the End of the Middle

Plotting the End

Something Happened

The Moment of Clarity

Filling the Emotional Void

Balancing the Plot Triad

Balancing the Plot Triad Part II

Creativity Abhors a Box

The Outline

An outline provides milestones along a story’s route and makes sure the writer hits his plot points while steering clear of detours. Of course, some wrong turns amount to genius, but an outline can help to identify what is genius and what is superfluous.

To Outline or Not To Outline

The Outline as Plot Development

Outline in Three Acts

Outlining The Ten Story Elements

Outlining The Ten Story Elements Cont’d

Creating Characters

Knowing what your characters need from you to take on a distinctive persona is integral to their creation and the success of your novel.

What goes into a great first line—a line so promising that readers commit to the next two chapters?

Characters & Plot

Memorable Characters

Identifiable Characters

Test of Time

The Character Profile

From Backstory to Front

The Heart of Character

Prince By Palace

Thoughts

Body Language

As A Man Speaks

Words Portray Character

Opinions

Actions

Through Another’s Eyes

Pressure

Character Check

A Unique Brand of Nice

Creating Funny Characters

The Fatal Flaw

Fatal Flaws in Literature, Film, & Television Characters

The Character Arc

The Enneagram Personalities

The Enneagram in Literature

By Any Other Name

Fiction’s Best Characters

Joseph Heller’s Yossarian from Catch-22

Anne Tyler’s Maggie Moran from Breathing Lessons: A Novel

The Lead

What goes into a great first line—a line so promising that readers commit to the next two chapters?

Your Novel’s All-Important Lead

Begin With Character

Begin With Place

Begin With Questions

Begin With Answers

Begin With The Problem

Begin With The Unprecedented

Pencil In a Title

7 Ways NOT to Begin Your Novel

100 Best Opening Lines

The Ending

What goes into a great ending—an ending so satisfying that readers commit to buying your next novel?

Endings Part I

Endings Part II

100 Best Novel Endings

Dialogue

The dos and don’ts of writing dialogue that will move your story forward while establishing characters.

Dialogue Part I

Write Between the Lines

Dialogue Is Adversarial

Internal Monologue

He Said, She Said

Dialogue Checklist

Humor

Everyone enjoys a laugh, but some writers are better than others when it comes to getting a chuckle from their readers. As E.B. White wrote, “Humor has a certain fragility, an evasiveness which one had best respect.” But understanding the patterns and repetitions that breach expectations, writers are able to craft the benign violations that tickle the brain and add to the texture of any genre piece.

Humor in Literature

The 1, 2, 3 of Humor

Humorous Imagery

Humorous Word Choice and Arrangement

Words With a Humorous Ring

Characters That Get Us Laughing

Humor Writing Exercises

Edits & Revisions

Editing is everything. Know what to look for and how to self-edit your novel.

Editing Your Manuscript

Editing Your Manuscript Part II

Re-Vision

Re-Vision Part II

Editing Checklist

TWITTER I FACEBOOK I GOOGLEPlus I PINTEREST I WEBSITE

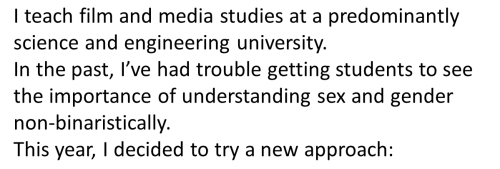

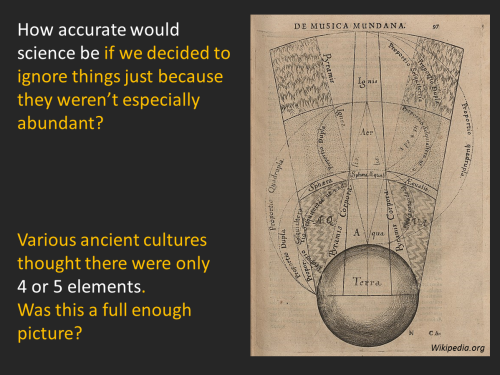

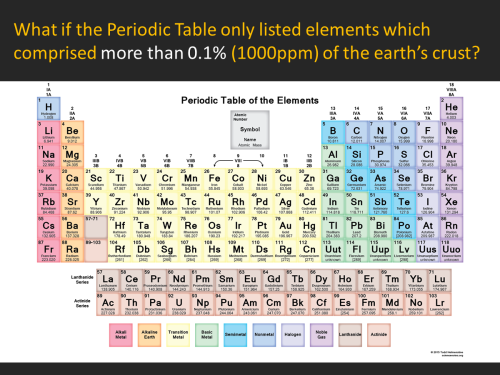

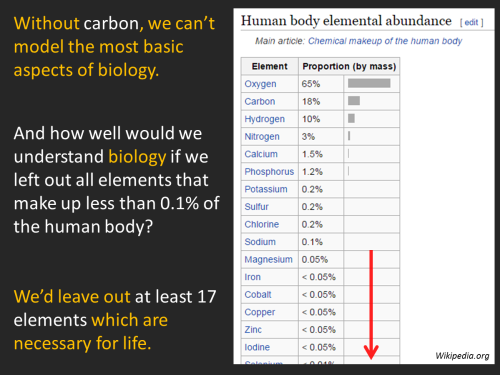

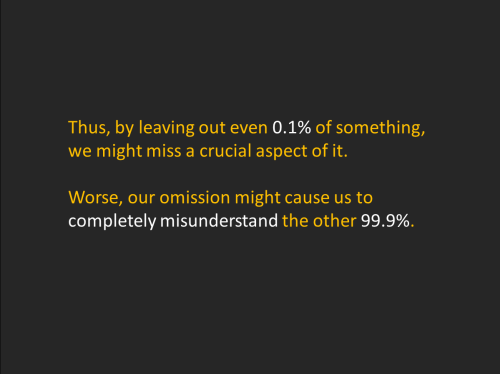

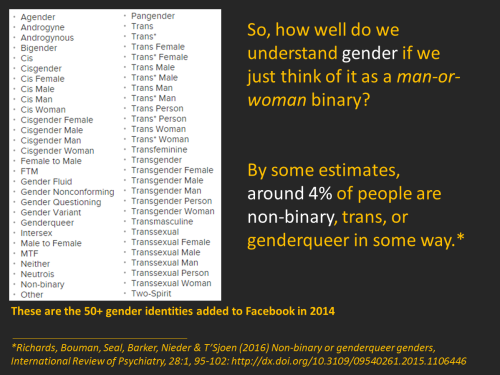

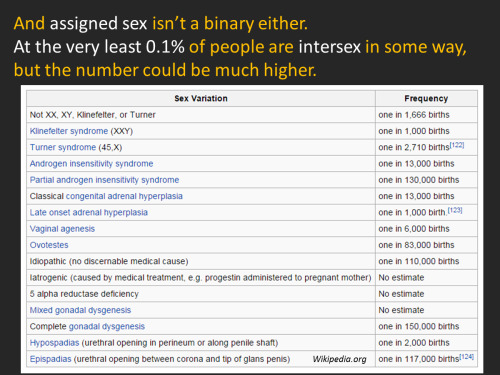

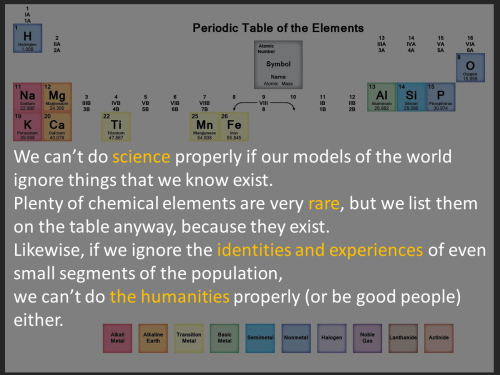

Saying that man and woman are the only genders is actually LESS nuanced than saying that earth, water, air, and fire are the only elements.

-

pblovesjelly reblogged this · 3 years ago

pblovesjelly reblogged this · 3 years ago -

pblovesjelly liked this · 3 years ago

pblovesjelly liked this · 3 years ago -

my-thoughts-and-junk reblogged this · 4 years ago

my-thoughts-and-junk reblogged this · 4 years ago -

esfinleo liked this · 5 years ago

esfinleo liked this · 5 years ago -

imagnesnutter liked this · 5 years ago

imagnesnutter liked this · 5 years ago -

w-e-chard liked this · 6 years ago

w-e-chard liked this · 6 years ago -

storieswritteninthesand liked this · 6 years ago

storieswritteninthesand liked this · 6 years ago -

cyclesofsaturn reblogged this · 6 years ago

cyclesofsaturn reblogged this · 6 years ago -

tsaget liked this · 6 years ago

tsaget liked this · 6 years ago -

jazzyvalor liked this · 6 years ago

jazzyvalor liked this · 6 years ago -

tedisafish reblogged this · 6 years ago

tedisafish reblogged this · 6 years ago -

unnez liked this · 6 years ago

unnez liked this · 6 years ago -

noirpunk101 liked this · 7 years ago

noirpunk101 liked this · 7 years ago -

disastervirgo liked this · 7 years ago

disastervirgo liked this · 7 years ago -

croissantsunite reblogged this · 7 years ago

croissantsunite reblogged this · 7 years ago -

croissantsunite liked this · 7 years ago

croissantsunite liked this · 7 years ago -

uhhhhhhmazinggrace liked this · 7 years ago

uhhhhhhmazinggrace liked this · 7 years ago -

mekana47 reblogged this · 7 years ago

mekana47 reblogged this · 7 years ago -

mekana47 liked this · 7 years ago

mekana47 liked this · 7 years ago -

razzjamjar reblogged this · 7 years ago

razzjamjar reblogged this · 7 years ago -

razzjamjar liked this · 7 years ago

razzjamjar liked this · 7 years ago -

tedisafish liked this · 7 years ago

tedisafish liked this · 7 years ago -

bat-besties liked this · 7 years ago

bat-besties liked this · 7 years ago -

jughead-is-canonically-aroace reblogged this · 7 years ago

jughead-is-canonically-aroace reblogged this · 7 years ago -

mari-lwyd reblogged this · 7 years ago

mari-lwyd reblogged this · 7 years ago -

beardedlady797 liked this · 7 years ago

beardedlady797 liked this · 7 years ago -

aslimewithagun liked this · 7 years ago

aslimewithagun liked this · 7 years ago -

is-icuisle liked this · 7 years ago

is-icuisle liked this · 7 years ago -

muffindounat liked this · 7 years ago

muffindounat liked this · 7 years ago -

nightingale-fall liked this · 7 years ago

nightingale-fall liked this · 7 years ago -

valiantnomore reblogged this · 7 years ago

valiantnomore reblogged this · 7 years ago -

valiantnomore liked this · 7 years ago

valiantnomore liked this · 7 years ago -

50shadesofwriting reblogged this · 7 years ago

50shadesofwriting reblogged this · 7 years ago -

jorammiireads reblogged this · 7 years ago

jorammiireads reblogged this · 7 years ago -

earthkills liked this · 7 years ago

earthkills liked this · 7 years ago -

carlyjyll liked this · 7 years ago

carlyjyll liked this · 7 years ago -

lost-in-a-story reblogged this · 7 years ago

lost-in-a-story reblogged this · 7 years ago -

mala-sadas liked this · 7 years ago

mala-sadas liked this · 7 years ago -

kleeley liked this · 7 years ago

kleeley liked this · 7 years ago -

flamelaz liked this · 7 years ago

flamelaz liked this · 7 years ago -

littlelonghairedoutlawllho reblogged this · 7 years ago

littlelonghairedoutlawllho reblogged this · 7 years ago -

littlelonghairedoutlawllho liked this · 7 years ago

littlelonghairedoutlawllho liked this · 7 years ago -

melwikwrites reblogged this · 7 years ago

melwikwrites reblogged this · 7 years ago -

faultyambition liked this · 7 years ago

faultyambition liked this · 7 years ago -

kianga reblogged this · 7 years ago

kianga reblogged this · 7 years ago