Riekod - 里枝子

More Posts from Riekod and Others

“The most powerful determinant of whether a woman goes on in science might be whether anyone encourages her to go on. My freshman year at Yale, I earned a 32 on my first physics midterm. My parents urged me to switch majors. All they wanted was that I be able to earn a living until I married a man who could support me, and physics seemed unlikely to accomplish either goal. I trudged up Science Hill to ask my professor, Michael Zeller, to sign my withdrawal slip. I took the elevator to Professor Zeller’s floor, then navigated corridors lined with photos of the all-male faculty and notices for lectures whose titles struck me as incomprehensible. I knocked at my professor’s door and managed to stammer that I had gotten a 32 on the midterm and needed him to sign my drop slip. “Why?” he asked. He received D’s in two of his physics courses. Not on the midterms — in the courses. The story sounded like something a nice professor would invent to make his least talented student feel less dumb. In his case, the D’s clearly were aberrations. In my case, the 32 signified that I wasn’t any good at physics. “Just swim in your own lane,” he said. Seeing my confusion, he told me that he had been on the swimming team at Stanford. His stroke was as good as anyone’s. But he kept coming in second. “Zeller,” the coach said, “your problem is you keep looking around to see how the other guys are doing. Keep your eyes on your own lane, swim your fastest and you’ll win.” I gathered this meant he wouldn’t be signing my drop slip. “You can do it,” he said. “Stick it out.” I stayed in the course. Week after week, I struggled to do my problem sets, until they no longer seemed impenetrable. The deeper I now tunnel into my four-inch-thick freshman physics textbook, the more equations I find festooned with comet-like exclamation points and theorems whose beauty I noted with exploding novas of hot-pink asterisks. The markings in the book return me to a time when, sitting in my cramped dorm room, I suddenly grasped some principle that governs the way objects interact, whether here on earth or light years distant, and I marveled that such vastness and complexity could be reducible to the equation I had highlighted in my book. Could anything have been more thrilling than comprehending an entirely new way of seeing, a reality more real than the real itself? I earned a B in the course; the next semester I got an A. By the start of my senior year, I was at the top of my class, with the most experience conducting research. But not a single professor asked me if I was going on to graduate school. When I mentioned shyly to Professor Zeller that my dream was to apply to Princeton and become a theoretician, he shook his head and said that if you went to Princeton, you had better put your ego in your back pocket, because those guys were so brilliant and competitive that you would get that ego crushed, which made me feel as if I weren’t brilliant or competitive enough to apply. Not even the math professor who supervised my senior thesis urged me to go on for a Ph.D. I had spent nine months missing parties, skipping dinners and losing sleep, trying to figure out why waves — of sound, of light, of anything — travel in a spherical shell, like the skin of a balloon, in any odd-dimensional space, but like a solid bowling ball in any space of even dimension. When at last I found the answer, I knocked triumphantly at my adviser’s door. Yet I don’t remember him praising me in any way. I was dying to ask if my ability to solve the problem meant that I was good enough to make it as a theoretical physicist. But I knew that if I needed to ask, I wasn’t.”

— Eileen Pollack (via logicandgrace)

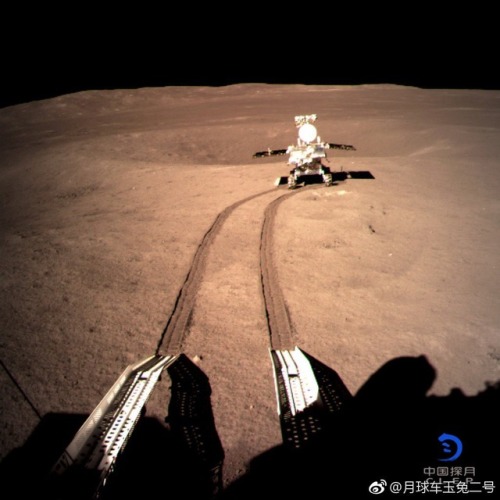

Chang'E-4: The Yutu-2 rover isn’t wasting any time, & has driven away from the lander toward (but not into) a nearby crater. Reminder that all photos from the far side of the moon are being relayed to earth by the Queqiao spacecraft, which is parked in a halo orbit around the Earth-Moon L2 point, about 61,500km behind the moon. “Halo orbit” means it’s about that far behind the moon, but always off to one side or the other from the actual L2 point so it has a line of sight to the Earth. Wouldn’t be much of a relay otherwise.

How Big is Our Galaxy, the Milky Way?

When we talk about the enormity of the cosmos, it’s easy to toss out big numbers – but far harder to wrap our minds around just how large, how far and how numerous celestial bodies like exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – really are.

So. How big is our Milky Way Galaxy?

We use light-time to measure the vast distances of space.

It’s the distance that light travels in a specific period of time. Also: LIGHT IS FAST, nothing travels faster than light.

How far can light travel in one second? 186,000 miles. It might look even faster in metric: 300,000 kilometers in one second. See? FAST.

How far can light travel in one minute? 11,160,000 miles. We’re moving now! Light could go around the Earth a bit more than 448 times in one minute.

Speaking of Earth, how long does it take light from the Sun to reach our planet? 8.3 minutes. (It takes 43.2 minutes for sunlight to reach Jupiter, about 484 million miles away.) Light is fast, but the distances are VAST.

In an hour, light can travel 671 million miles. We’re still light-years from the nearest exoplanet, by the way. Proxima Centauri b is 4.2 light-years away. So… how far is a light-year? 5.8 TRILLION MILES.

A trip at light speed to the very edge of our solar system – the farthest reaches of the Oort Cloud, a collection of dormant comets way, WAY out there – would take about 1.87 years.

Our galaxy contains 100 to 400 billion stars and is about 100,000 light-years across!

One of the most distant exoplanets known to us in the Milky Way is Kepler-443b. Traveling at light speed, it would take 3,000 years to get there. Or 28 billion years, going 60 mph. So, you know, far.

SPACE IS BIG.

Read more here: go.nasa.gov/2FTyhgH

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

The Magellanic Clouds are two irregular dwarf galaxies visible in the Southern Celestial Hemisphere; they are members of the Local Group and are orbiting the Milky Way galaxy. Because they both show signs of a bar structure, they are often reclassified as Magellanic spiral galaxies. The two galaxies are:

Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), approximately 160,000 light-years away.

Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), approximately 200,000 light years away.

source

Image credit: Primoz Cigler, Joseph Brimacombe, Ed Dunens and EkantTakePhotos

Venus, Jupiter and Mars at Dawn - Oct 22, 2015

Image credit: Joseph Brimacombe

The triple point of water

Retrograde motion of Mars in the night sky of the Earth.

Image Credit: Tunc Tezel

-

vczn reblogged this · 8 months ago

vczn reblogged this · 8 months ago -

aeyriabird reblogged this · 9 months ago

aeyriabird reblogged this · 9 months ago -

sophisticated-dorkk reblogged this · 10 months ago

sophisticated-dorkk reblogged this · 10 months ago -

thelilpumpkin reblogged this · 10 months ago

thelilpumpkin reblogged this · 10 months ago -

sophisticated-dorkk liked this · 10 months ago

sophisticated-dorkk liked this · 10 months ago -

pluganplay liked this · 10 months ago

pluganplay liked this · 10 months ago -

alanisblogfan liked this · 10 months ago

alanisblogfan liked this · 10 months ago -

multifandomor liked this · 10 months ago

multifandomor liked this · 10 months ago -

dew-ontherocks liked this · 10 months ago

dew-ontherocks liked this · 10 months ago -

mischief-from-the-void reblogged this · 10 months ago

mischief-from-the-void reblogged this · 10 months ago -

thatgirlrobyn97 liked this · 10 months ago

thatgirlrobyn97 liked this · 10 months ago -

kz-midnitesnail liked this · 10 months ago

kz-midnitesnail liked this · 10 months ago -

boudicca-22153 reblogged this · 10 months ago

boudicca-22153 reblogged this · 10 months ago -

boudicca-22153 liked this · 10 months ago

boudicca-22153 liked this · 10 months ago -

distresseddove reblogged this · 10 months ago

distresseddove reblogged this · 10 months ago -

distresseddove liked this · 10 months ago

distresseddove liked this · 10 months ago -

belongingtobusra reblogged this · 10 months ago

belongingtobusra reblogged this · 10 months ago -

jayne-doe liked this · 10 months ago

jayne-doe liked this · 10 months ago -

undertheghost reblogged this · 10 months ago

undertheghost reblogged this · 10 months ago -

somethingtocallmine liked this · 10 months ago

somethingtocallmine liked this · 10 months ago -

aeyriabird liked this · 10 months ago

aeyriabird liked this · 10 months ago -

stellarlovely reblogged this · 10 months ago

stellarlovely reblogged this · 10 months ago -

tewz liked this · 1 year ago

tewz liked this · 1 year ago -

zyemcarasophia liked this · 1 year ago

zyemcarasophia liked this · 1 year ago -

locasnickers reblogged this · 1 year ago

locasnickers reblogged this · 1 year ago -

locasnickers liked this · 1 year ago

locasnickers liked this · 1 year ago -

nebris reblogged this · 1 year ago

nebris reblogged this · 1 year ago -

nebris liked this · 1 year ago

nebris liked this · 1 year ago -

alexistheheathen reblogged this · 1 year ago

alexistheheathen reblogged this · 1 year ago -

hiphappyhair reblogged this · 1 year ago

hiphappyhair reblogged this · 1 year ago -

hiphappyhair liked this · 1 year ago

hiphappyhair liked this · 1 year ago -

elusiveladydjinn liked this · 2 years ago

elusiveladydjinn liked this · 2 years ago -

daddyrules024 liked this · 2 years ago

daddyrules024 liked this · 2 years ago -

oneimpulsivegal liked this · 2 years ago

oneimpulsivegal liked this · 2 years ago -

alex98cabrera liked this · 3 years ago

alex98cabrera liked this · 3 years ago -

najlaf98 liked this · 3 years ago

najlaf98 liked this · 3 years ago -

maxemilianverstappen liked this · 3 years ago

maxemilianverstappen liked this · 3 years ago -

thebest10015 liked this · 3 years ago

thebest10015 liked this · 3 years ago -

doyouwannaloveme reblogged this · 4 years ago

doyouwannaloveme reblogged this · 4 years ago -

doyouwannaloveme liked this · 4 years ago

doyouwannaloveme liked this · 4 years ago -

retrograde-raven reblogged this · 4 years ago

retrograde-raven reblogged this · 4 years ago -

retrograde-raven liked this · 4 years ago

retrograde-raven liked this · 4 years ago -

brothersonahotelbed liked this · 4 years ago

brothersonahotelbed liked this · 4 years ago -

kidd-corvid reblogged this · 4 years ago

kidd-corvid reblogged this · 4 years ago -

pavlovscrow liked this · 4 years ago

pavlovscrow liked this · 4 years ago