“I Want Us To Be Doing Things, Prolonging Life’s Duties As Much As We Can. I Want Death To Find Me

“I want us to be doing things, prolonging life’s duties as much as we can. I want death to find me planting my cabbages, neither worrying about it nor the unfinished gardening.” ― Michel de Montaigne

More Posts from Thxsdad and Others

Hope posting

Song: The Orb of Dreamers by The Daniel Pemberton TV Orchestra

From Anthony Bourdain:

Americans love Mexican food. We consume nachos, tacos, burritos, tortas, enchiladas, tamales and anything resembling Mexican in enormous quantities. We love Mexican beverages, happily knocking back huge amounts of tequila, mezcal, and Mexican beer every year. We love Mexican people—we sure employ a lot of them.

Despite our ridiculously hypocritical attitudes towards immigration, we demand that Mexicans cook a large percentage of the food we eat, grow the ingredients we need to make that food, clean our houses, mow our lawns, wash our dishes, and look after our children.

As any chef will tell you, our entire service economy—the restaurant business as we know it—in most American cities, would collapse overnight without Mexican workers. Some, of course, like to claim that Mexicans are “stealing American jobs.”

But in two decades as a chef and employer, I never had ONE American kid walk in my door and apply for a dishwashing job, a porter’s position—or even a job as a prep cook. Mexicans do much of the work in this country that Americans, probably, simply won’t do.

We love Mexican drugs. Maybe not you personally, but “we”, as a nation, certainly consume titanic amounts of them—and go to extraordinary lengths and expense to acquire them. We love Mexican music, Mexican beaches, Mexican architecture, interior design, Mexican films.

So, why don’t we love Mexico?

We throw up our hands and shrug at what happens and what is happening just across the border. Maybe we are embarrassed. Mexico, after all, has always been there for us, to service our darkest needs and desires.

Whether it’s dress up like fools and get passed-out drunk and sunburned on spring break in Cancun, throw pesos at strippers in Tijuana, or get toasted on Mexican drugs, we are seldom on our best behavior in Mexico. They have seen many of us at our worst. They know our darkest desires.

In the service of our appetites, we spend billions and billions of dollars each year on Mexican drugs—while at the same time spending billions and billions more trying to prevent those drugs from reaching us.

The effect on our society is everywhere to be seen. Whether it’s kids nodding off and overdosing in small town Vermont, gang violence in L.A., burned out neighborhoods in Detroit—it’s there to see.

What we don’t see, however, haven’t really noticed, and don’t seem to much care about, is the 80,000 dead in Mexico, just in the past few years—mostly innocent victims. Eighty thousand families who’ve been touched directly by the so-called “War On Drugs”.

Mexico. Our brother from another mother. A country, with whom, like it or not, we are inexorably, deeply involved, in a close but often uncomfortable embrace.

Look at it. It’s beautiful. It has some of the most ravishingly beautiful beaches on earth. Mountains, desert, jungle. Beautiful colonial architecture, a tragic, elegant, violent, ludicrous, heroic, lamentable, heartbreaking history. Mexican wine country rivals Tuscany for gorgeousness.

It's archeological sites—the remnants of great empires, unrivaled anywhere. And as much as we think we know and love it, we have barely scratched the surface of what Mexican food really is. It is NOT melted cheese over tortilla chips. It is not simple, or easy. It is not simply “bro food” at halftime.

It is in fact, old—older even than the great cuisines of Europe, and often deeply complex, refined, subtle, and sophisticated. A true mole sauce, for instance, can take DAYS to make, a balance of freshly (always fresh) ingredients painstakingly prepared by hand. It could be, should be, one of the most exciting cuisines on the planet, if we paid attention.

The old school cooks of Oaxaca make some of the more difficult and nuanced sauces in gastronomy. And some of the new generation—many of whom have trained in the kitchens of America and Europe—have returned home to take Mexican food to new and thrilling heights.

It’s a country I feel particularly attached to and grateful for. In nearly 30 years of cooking professionally, just about every time I walked into a new kitchen, it was a Mexican guy who looked after me, had my back, showed me what was what, and was there—and on the case—when the cooks like me, with backgrounds like mine, ran away to go skiing or surfing or simply flaked. I have been fortunate to track where some of those cooks come from, to go back home with them.

To small towns populated mostly by women—where in the evening, families gather at the town’s phone kiosk, waiting for calls from their husbands, sons and brothers who have left to work in our kitchens in the cities of the North.

I have been fortunate enough to see where that affinity for cooking comes from, to experience moms and grandmothers preparing many delicious things, with pride and real love, passing that food made by hand from their hands to mine.

In years of making television in Mexico, it’s one of the places we, as a crew, are happiest when the day’s work is over. We’ll gather around a street stall and order soft tacos with fresh, bright, delicious salsas, drink cold Mexican beer, sip smoky mezcals, and listen with moist eyes to sentimental songs from street musicians. We will look around and remark, for the hundredth time, what an extraordinary place this is.

![Carroll Cloar, Moonstricken Girls, 1968 [Arkansas Museum Of Fine Arts Foundation Collection]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/460cac3507d0986220aebbf0b11c61a9/94a63df4f16b8c53-e9/s500x750/ff9fab256dc1c23a7638001b425db4d22b341450.jpg)

Carroll Cloar, Moonstricken Girls, 1968 [Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts Foundation Collection]

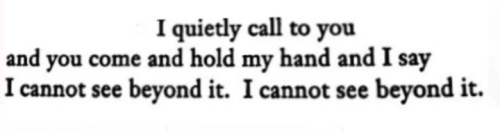

Olena Kalytiak Davis, Shattered Sonnets, Love Cards, and Other Off and Back Handed Importunities

Sharon Olds, True Love

Stephen Crane, In The Desert

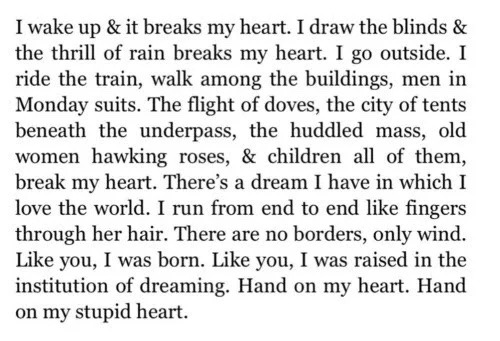

Cameron Awkward-Rich, Meditations in an Emergency

ANTIGONE: The fields were wet. They were waiting for something to happen. The whole world was breathless, waiting. I can’t tell you what a roaring noise I seemed to make alone on the road. It bothered me that whatever was waiting, wasn’t waiting for me.

Jean Anouilh, Antigone

Etel Adnan, The Spring Flowers Own & The Manifestations of the Voyage

I’m trying to give you everything I have. But I can’t find it; I can’t find it yet.

Alice Notley, In The Pines

Anne Carson, Plainwater: Essays and Poetry

& if I were to forgive you (& I know I could)

who would be left

who would be left

to forgive me?

Hieu Minh Nguyen, Afterwards

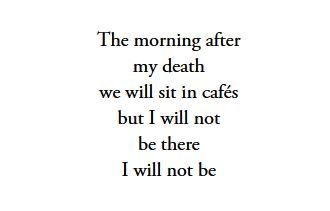

Mahmoud Darwish, Mural

Fariha Róisín, How to Cure a Ghost

“You kiss the back of my legs and I want to cry. Only / the sun has come this close, only the sun.”

Shauna Barbosa, GPS

Mahmoud Darwish, Mural

Forough Farrokhzad, Another Birth

repetition in poetry // part i

Roberto Burle Marx

Burle Marx’s most famed completed commission in the U.S. was Miami’s vast, mosaic-embedded Biscayne Boulevard (1988–2004).

The Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994) worked in a variety of artistic mediums, from painting and sculpture to graphic design and mosaics.

Keep reading

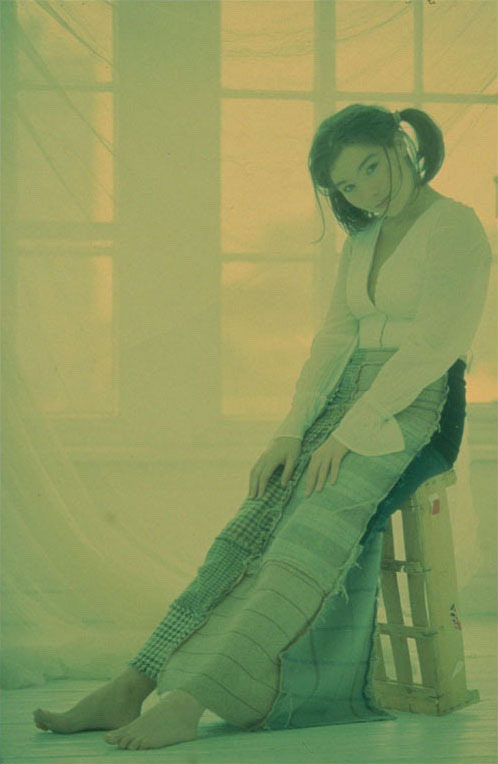

Björk 1993

Photographed by Sheridan Morley

Tyler the Creator, 2021

Ol' Dirty Bastard, 1995

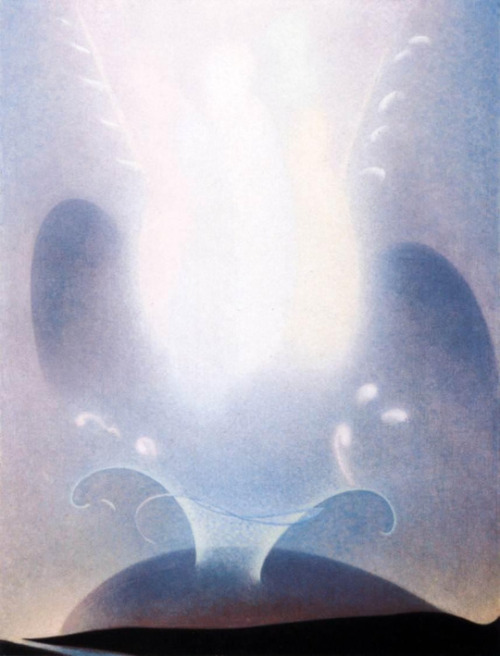

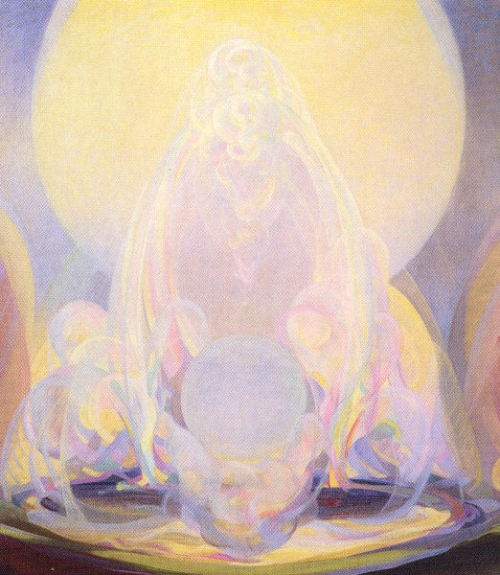

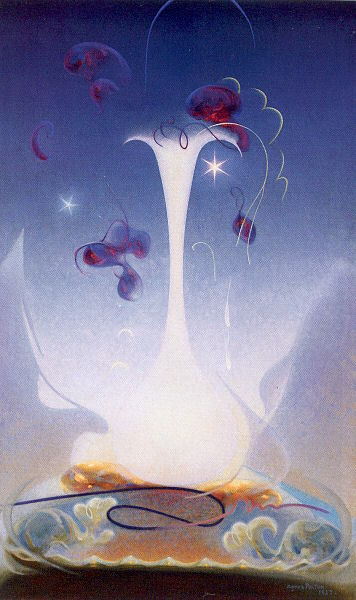

Agnes Pelton (American, 1881–1961)

The Blest, n.d.

The Fountains, 1926

Sand Storm, 1932

Memory, 1937

More on hideback

Adam Burke

Capri Noctis, 2018

Acrylic on woood

my favorite part about not doing anything ever is

-

dumbasshoyo reblogged this · 1 month ago

dumbasshoyo reblogged this · 1 month ago -

impluvia liked this · 1 month ago

impluvia liked this · 1 month ago -

stalekoolaidx liked this · 1 month ago

stalekoolaidx liked this · 1 month ago -

wombwound23 liked this · 1 month ago

wombwound23 liked this · 1 month ago -

thenightlymirror liked this · 1 month ago

thenightlymirror liked this · 1 month ago -

tropicalmalady liked this · 1 month ago

tropicalmalady liked this · 1 month ago -

sscullysglasses reblogged this · 1 month ago

sscullysglasses reblogged this · 1 month ago -

youknowwobbles liked this · 1 month ago

youknowwobbles liked this · 1 month ago -

adriantripods reblogged this · 1 month ago

adriantripods reblogged this · 1 month ago -

adriantripods liked this · 1 month ago

adriantripods liked this · 1 month ago -

heretopasstimebi liked this · 1 month ago

heretopasstimebi liked this · 1 month ago -

nattvvi liked this · 1 month ago

nattvvi liked this · 1 month ago -

nattvvi reblogged this · 1 month ago

nattvvi reblogged this · 1 month ago -

daytrader-vader liked this · 1 month ago

daytrader-vader liked this · 1 month ago -

go-out-of-wonderland liked this · 1 month ago

go-out-of-wonderland liked this · 1 month ago -

charlottie4 liked this · 1 month ago

charlottie4 liked this · 1 month ago -

drinkthemlock reblogged this · 1 month ago

drinkthemlock reblogged this · 1 month ago -

allpurposelesbian liked this · 1 month ago

allpurposelesbian liked this · 1 month ago -

cattyycat reblogged this · 1 month ago

cattyycat reblogged this · 1 month ago -

thequietabsolute liked this · 1 month ago

thequietabsolute liked this · 1 month ago -

lovrcide liked this · 1 month ago

lovrcide liked this · 1 month ago -

priv0123 reblogged this · 1 month ago

priv0123 reblogged this · 1 month ago -

jazbina reblogged this · 1 month ago

jazbina reblogged this · 1 month ago -

jazbina liked this · 1 month ago

jazbina liked this · 1 month ago -

pettydemon reblogged this · 1 month ago

pettydemon reblogged this · 1 month ago -

saintshiv liked this · 1 month ago

saintshiv liked this · 1 month ago -

plutoismyfavplanet reblogged this · 1 month ago

plutoismyfavplanet reblogged this · 1 month ago -

forsurenotaniczka reblogged this · 1 month ago

forsurenotaniczka reblogged this · 1 month ago -

forsurenotaniczka liked this · 1 month ago

forsurenotaniczka liked this · 1 month ago -

meu-nome-e-odio reblogged this · 1 month ago

meu-nome-e-odio reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ithvka reblogged this · 1 month ago

ithvka reblogged this · 1 month ago -

in-the-mouth-of-madness reblogged this · 1 month ago

in-the-mouth-of-madness reblogged this · 1 month ago -

in-the-mouth-of-madness liked this · 1 month ago

in-the-mouth-of-madness liked this · 1 month ago -

kindestwalkingmentalbreakdown reblogged this · 1 month ago

kindestwalkingmentalbreakdown reblogged this · 1 month ago -

kindestwalkingmentalbreakdown liked this · 1 month ago

kindestwalkingmentalbreakdown liked this · 1 month ago -

thestarfool reblogged this · 1 month ago

thestarfool reblogged this · 1 month ago -

thestarfool liked this · 1 month ago

thestarfool liked this · 1 month ago -

myshkins-epilepsy liked this · 1 month ago

myshkins-epilepsy liked this · 1 month ago -

behometonight reblogged this · 1 month ago

behometonight reblogged this · 1 month ago -

behometonight liked this · 1 month ago

behometonight liked this · 1 month ago -

leighcunt liked this · 1 month ago

leighcunt liked this · 1 month ago -

yeahbutwhyy liked this · 1 month ago

yeahbutwhyy liked this · 1 month ago -

vjecitiapril reblogged this · 1 month ago

vjecitiapril reblogged this · 1 month ago -

jaytaycee liked this · 1 month ago

jaytaycee liked this · 1 month ago -

tvglow liked this · 1 month ago

tvglow liked this · 1 month ago -

livinglibrary liked this · 1 month ago

livinglibrary liked this · 1 month ago -

bs-03 liked this · 1 month ago

bs-03 liked this · 1 month ago -

olivebean22 liked this · 1 month ago

olivebean22 liked this · 1 month ago -

nighthawkes reblogged this · 1 month ago

nighthawkes reblogged this · 1 month ago -

nighthawkes liked this · 1 month ago

nighthawkes liked this · 1 month ago