Why Webb Needs To Chill

Why Webb Needs to Chill

Our massive James Webb Space Telescope is currently being tested to make sure it can work perfectly at incredibly cold temperatures when it’s in deep space.

How cold is it getting and why? Here’s the whole scoop…

Webb is a giant infrared space telescope that we are currently building. It was designed to see things that other telescopes, even the amazing Hubble Space Telescope, can’t see.

Webb’s giant 6.5-meter diameter primary mirror is part of what gives it superior vision, and it’s coated in gold to optimize it for seeing infrared light.

Why do we want to see infrared light?

Lots of stuff in space emits infrared light, so being able to observe it gives us another tool for understanding the universe. For example, sometimes dust obscures the light from objects we want to study – but if we can see the heat they are emitting, we can still “see” the objects to study them.

It’s like if you were to stick your arm inside a garbage bag. You might not be able to see your arm with your eyes – but if you had an infrared camera, it could see the heat of your arm right through the cooler plastic bag.

Credit: NASA/IPAC

With a powerful infrared space telescope, we can see stars and planets forming inside clouds of dust and gas.

We can also see the very first stars and galaxies that formed in the early universe. These objects are so far away that…well, we haven’t actually been able to see them yet. Also, their light has been shifted from visible light to infrared because the universe is expanding, and as the distances between the galaxies stretch, the light from them also stretches towards redder wavelengths.

We call this phenomena “redshift.” This means that for us, these objects can be quite dim at visible wavelengths, but bright at infrared ones. With a powerful enough infrared telescope, we can see these never-before-seen objects.

We can also study the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars. Many of the elements and molecules we want to study in planetary atmospheres have characteristic signatures in the infrared.

Because infrared light comes from objects that are warm, in order to detect the super faint heat signals of things that are really, really far away, the telescope itself has to be very cold. How cold does the telescope have to be? Webb’s operating temperature is under 50K (or -370F/-223 C). As a comparison, water freezes at 273K (or 32 F/0 C).

How do we keep the telescope that cold?

Because there is no atmosphere in space, as long as you can keep something out of the Sun, it will get very cold. So Webb, as a whole, doesn’t need freezers or coolers - instead it has a giant sunshield that keeps it in the shade. (We do have one instrument on Webb that does have a cryocooler because it needs to operate at 7K.)

Also, we have to be careful that no nearby bright things can shine into the telescope – Webb is so sensitive to faint infrared light, that bright light could essentially blind it. The sunshield is able to protect the telescope from the light and heat of the Earth and Moon, as well as the Sun.

Out at what we call the Second Lagrange point, where the telescope will orbit the Sun in line with the Earth, the sunshield is able to always block the light from bright objects like the Earth, Sun and Moon.

How do we make sure it all works in space?

By lots of testing on the ground before we launch it. Every piece of the telescope was designed to work at the cold temperatures it will operate at in space and was tested in simulated space conditions. The mirrors were tested at cryogenic temperatures after every phase of their manufacturing process.

The instruments went through multiple cryogenic tests at our Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

Once the telescope (instruments and optics) was assembled, it even underwent a full end-to-end test in our Johnson Space Center’s giant cryogenic chamber, to ensure the whole system will work perfectly in space.

What’s next for Webb?

It will move to Northrop Grumman where it will be mated to the sunshield, as well as the spacecraft bus, which provides support functions like electrical power, attitude control, thermal control, communications, data handling and propulsion to the spacecraft.

Learn more about the James Webb Space Telescope HERE, or follow the mission on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

More Posts from Xyhor-astronomy and Others

Apollo 11 Launch

Stormy Seas in Sagittarius

This new NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image shows the center of the Lagoon Nebula, an object with a deceptively tranquil name, in the constellation of Sagittarius. The region is filled with intense winds from hot stars, churning funnels of gas, and energetic star formation, all embedded within an intricate haze of gas and pitch-dark dust.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL/ESA/J. Trauger

The Extraordinary Core of a Neutron Star

Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Quanta Magazine; Source: Feryal Özel

This stunning multi-mission picture shows off the many sides of the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A. It is made up of images taken by three of NASA’s Great Observatories, using three different wavebands of light. Infrared data from the Spitzer Space Telescope are colored red; visible data from the Hubble Space Telescope are yellow; and X-ray data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory are green and blue.

Image credit: NSA/JPL

Should there be a holiday called Astronomy Day?

Where lights are to be turned off for the entire night so everyone could see the stars?

The Largest Black Hole Merger Of All-Time Is Coming, And Soon

“Over in Andromeda, the nearest large galaxy to the Milky Way, a number of unusual systems have been found. One of them, J0045+41, was originally thought to be two stars orbiting one another with a period of just 80 days. When additional observations were taken in the X-ray, they revealed a surprise: J0045+41 weren’t stars at all.”

When you look at any narrow region of the sky, you don’t simply see what’s in front of you. Rather, you see everything along your line-of-sight, as far as your observing power can take you. In the case of the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury, where hundreds of millions of stars were captured in impressive fashion, background objects thousands of times as distant can also be seen. One of them, J0045+41, was originally thought to be a binary star system that was quite tight: with just an 80 day orbital period. Follow-up observations in the X-ray, however, revealed that it wasn’t a binary star system after all, but an ultra-distant supermassive black hole pair, destined to merge in as little as 350 years. If we build the right observatory in space, we’ll be able to observe the entire inspiral-and-merger process for as long as we like!

Come get the full story, and some incredible pictures and visuals, on today’s Mostly Mute Monday!

To Scale Solar System Replica in the Desert!

Flying Monsters of Scorpius | Yuriy Toropin

Solar System: 10 Things to Know This Week

Need some space?

Here are 10 perspective-building images for your computer desktop and mobile device wallpaper.

These are all real images, sent very recently by our planetary missions throughout the solar system.

1. Our Sun

Warm up with this view from our Solar Dynamics Observatory showing active regions on the Sun in October 2017. They were observed in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light that reveals plasma heated to over a million degrees.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

2. Jupiter Up-Close

This series of enhanced-color images shows Jupiter up close and personal, as our Juno spacecraft performed its eighth flyby of the gas giant planet on Sept. 1, 2017.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

3. Saturn’s and Its Rings

With this mosaic from Oct. 28, 2016, our Cassini spacecraft captured one of its last looks at Saturn and its main rings from a distance.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

4. Gale Crater on Mars

This look from our Curiosity Mars rover includes several geological layers in Gale crater to be examined by the mission, as well as the higher reaches of Mount Sharp beyond. The redder rocks of the foreground are part of the Murray formation. Pale gray rocks in the middle distance of the right half of the image are in the Clay Unit. A band between those terrains is “Vera Rubin Ridge,” where the rover is working currently. The view combines six images taken with the rover’s Mast Camera (Mastcam) on Jan. 24, 2017.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

5. Sliver of Saturn

Cassini peers toward a sliver of Saturn’s sunlit atmosphere while the icy rings stretch across the foreground as a dark band on March 31, 2017. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 7 degrees below the ring plane.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

6. Dwarf Planet Ceres

This image of the limb of dwarf planet Ceres shows a section of the northern hemisphere, as seen by our Dawn mission. Prominently featured is Occator Crater, home of Ceres’ intriguing “bright spots.” The latest research suggests that the bright material in this crater is comprised of salts left behind after a briny liquid emerged from below.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

7. Martian Crater

This image from our Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) shows a crater in the region with the most impressive known gully activity in Mars’ northern hemisphere. Gullies are active in the winter due to carbon dioxide frost, but northern winters are shorter and warmer than southern winters, so there is less frost and less gully activity.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

8. Dynamic Storm on Jupiter

A dynamic storm at the southern edge of Jupiter’s northern polar region dominates this Jovian cloudscape, courtesy of Juno. This storm is a long-lived anticyclonic oval named North North Temperate Little Red Spot 1. Citizen scientists Gerald Eichstädt and Seán Doran processed this image using data from the JunoCam imager.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

9. Rings Beyond Saturn’s Sunlit Horizon

This false-color view from the Cassini spacecraft gazes toward the rings beyond Saturn’s sunlit horizon. Along the limb (the planet’s edge) at left can be seen a thin, detached haze.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

10. Saturn’s Ocean-Bearing Moon Enceladus

Saturn’s active, ocean-bearing moon Enceladus sinks behind the giant planet in a farewell portrait from Cassini. This view of Enceladus was taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on Sept. 13, 2017. It is among the last images Cassini sent back before its mission came to an end on Sept. 15, after nearly 20 years in space.

Downloads Desktop: 1280 x 800 | 1600 x 1200 | 1920 x 1200 Mobile: 1440 x 2560 | 1080 x 1920 | 750 x 1334

Applying Wallpaper: 1. Click on the screen resolution you would like to use. 2. Right-click on the image (control-click on a Mac) and select the option ‘Set the Background’ or 'Set as Wallpaper’ (or similar).

Places to look for more of our pictures include solarsystem.nasa.gov/galleries, images.nasa.gov and www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

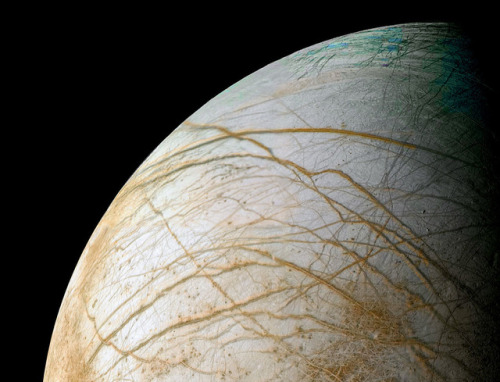

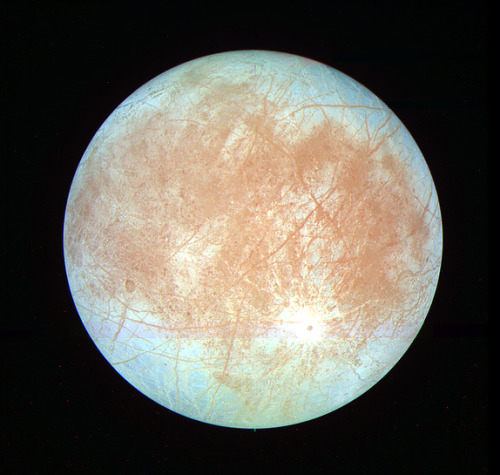

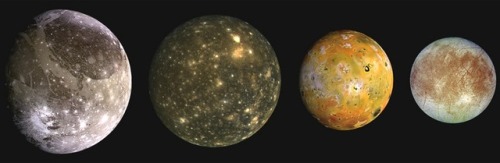

Europa

Jupiter’s moon Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. Its surface is smooth and bright, consisting of water ice crisscrossed by long, linear fractures. Like our planet, Europa is thought to have an iron core, a rocky mantle and an ocean of salty water beneath its ice crust. Unlike Earth, however, this ocean would be deep enough to extend from the moon’s surface to the top of its rocky mantle. Being far from the sun, the ocean’s surface would be globally frozen over. While evidence for this internal ocean is quite strong, its presence awaits confirmation by a future mission.

Europa orbits Jupiter every 3.5 days and is locked by gravity to Jupiter such that the same hemisphere of the moon always faces the planet. Because Europa’s orbit is slightly stretched out from circular, or elliptical, its distance from Jupiter varies, creating tides that stretch and relax its surface. The tides occur because Jupiter’s gravity is just slightly stronger on the near side of the moon than on the far side, and the magnitude of this difference changes as Europa orbits. Flexing from the tides supplies energy to the moon’s icy shell, creating the linear fractures across its surface. If Europa’s ocean exists, the tides might also create volcanic or hydrothermal activity on the seafloor, supplying nutrients that could make the ocean suitable for living things.

Europa Clipper

NASA’s planned Europa Clipper would conduct detailed reconnaissance of Jupiter’s moon Europa and investigate whether the icy moon could harbor conditions suitable for life.

The mission would place a spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter in order to perform a detailed investigation of the giant planet’s moon Europa – a world that shows strong evidence for an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust and which could host conditions favorable for life. The mission would send a highly capable, radiation-tolerant spacecraft into a long, looping orbit around Jupiter to perform repeated close flybys of Europa. NASA has selected nine science instruments for a future mission to Europa. The selected payload includes cameras and spectrometers to produce high-resolution images of Europa’s surface and determine its composition. An ice penetrating radar would determine the thickness of the moon’s icy shell and search for subsurface lakes similar to those beneath Antarctica’s ice sheet. The mission would also carry a magnetometer to measure the strength and direction of the moon’s magnetic field, which would allow scientists to determine the depth and salinity of its ocean.

Image credit: NASA / JPL / Galileo / Voyager & Processed by Kevin M. Gill

Credit: NASA & Europa Clipper Mission

-

helder4u reblogged this · 1 year ago

helder4u reblogged this · 1 year ago -

helder4u liked this · 1 year ago

helder4u liked this · 1 year ago -

dmw10444 liked this · 4 years ago

dmw10444 liked this · 4 years ago

For more content, Click Here and experience this XYHor in its entirety!Space...the Final Frontier. Let's boldly go where few have gone before with XYHor: Space: Astronomy & Spacefaring: the collection of the latest finds and science behind exploring our solar system, how we'll get there and what we need to be prepared for!

128 posts