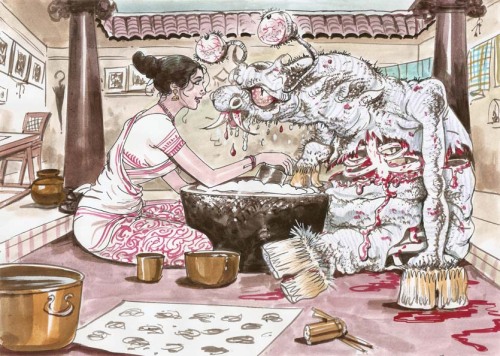

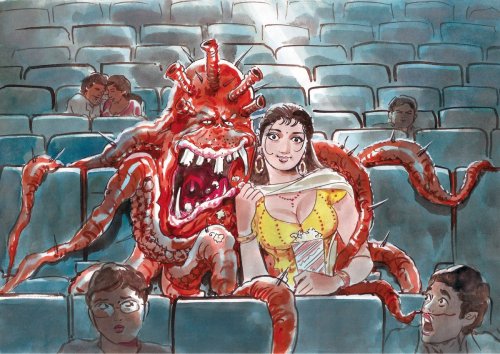

Art From Kumari Loves A Monster By Rashmi Devadasan. Illustrated By Shyam.

Art from Kumari Loves a Monster by Rashmi Devadasan. Illustrated by Shyam.

“The young maidens in these pages all have beauty, brains and talent / They while away the night and day / With monsters fierce and gallant.

A romantic picture book of young girls who have fallen in love with monsters.”

More Posts from Absiesfeed and Others

At the very centre of the image above is something incredible - a single, positively-charged strontium atom, suspended in motion by electric fields.

Not only is this an incredibly rare sight, it’s also difficult to wrap your head around the fact that this tiny point of blue light is a building block of matter.

The image was captured by physicist David Nadlinger from the University of Oxford, and it’s been awarded the overall prize in the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council photo competition.

To give you a little perspective on the size of this set-up, the atom is being held in place by electric fields emanating from those two metal needles on either side of it.

The distance between them is about 2 millimetres (0.08 inch).

The atom is being illuminated by a blue-violet laser. The energy from the laser causes the atom to emit photons which Nadlinger could capture on camera using a long exposure.

The whole thing is housed inside an ultra-high vacuum chamber and dramatically cooled to keep the atom still. Nadlinger took this photo through the window of the vacuum chamber.

To learn more, click here.

William Scully (American, b. 1967, based Boston, MA, USA) - 1: Water Lily Study No. 18 2: Water Lily Study No. 20, Underwater Photography

La sonda DART de la NASA ha chocado contra un asteroide en la primera prueba de defensa planetaria

La sonda DART de la NASA ha chocado contra un asteroide en la primera prueba de defensa planetaria

La misión DART de la NASA ha chocado contra un asteroide para intentar variar su órbita. La ha lanzado contra una pequeña luna de un asteroide doble llamado Didymos , la sonda del tamaño un coche pequeño, llamada DART (Doble Asteroid Redirection Test), ha chocado deliberadamente contra la luna del asteroide llamada Dimorphos. Esto es solo una prueba, ya que ni el asteroide Didymos ni su luna…

View On WordPress

Check it out

Long Exposure Photos Capture the Light Paths of Drones Above Mountainous Landscapes

Life of Pi (Ang Lee, 2012).

“You want a tea?

“No, I want romance. I want music. I want love and beauty.

“But not tea, eh? Amazing …”

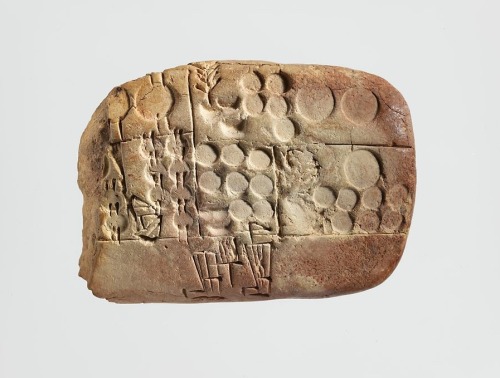

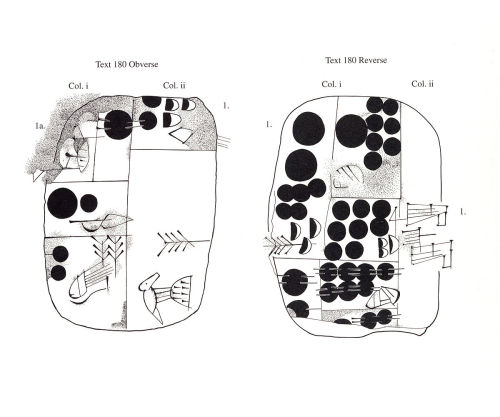

Sumerian cuneiform tablet (c. 3100 – 2900 BC). Administrative account recording the distribution of barley and emmer wheat. Probably from Uruk (Warka, Iraq).

The first system of writing in the world was developed by the Sumerians, beginning c. 3500 – 3000 BC. It was the most significant of Sumer’s cultural contributions, and much of this development happened in the city of Uruk.

A stylus was used to creat wedge-like impresssions in soft clay, and the clay was fired afterwards. The word “cuneiform” comes from the Latin cuneus, meaning “wedge”.

These wedge-like impressions were first pictographs, and later on phonograms (symbols representing vocal sounds) and “word-concepts” – closer to a modern-day understanding of words and writing. All the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform, including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Hatti, Hittites, Assyrians and Hurrians. Around 100 BC, it was abandoned in favour of the alphabetic script.

The earliest texts used proto-cuneiform, and were pictorial. Writing was a technique for noting down things, items and objects (e.g. Two Sheep Temple God Inanna). This system worked well for concrete, visible subjects, but could give little in the way of details. As subject matter became more intangible (e.g. the will of the gods, the quest for immortality), cuneiform developed in complexity to represent this.

By 3000 BC, the representations were more simplified. The stylus’ impressions conveyed word-concepts rather than word-signs – for example, the scribe could write about the more abstract concept of “honour”, rather than having to specifically depict “an honourable man”.

The “rebus” principle was used to isolate the phonetic (sound) value of a particular sign. Rebus is a device that combines pictures (or pictographs) with individual letters to depict words and/or phrases. For example, the picture of a bumblebee followed by the letter “n” would represent the word “been”. With the rebus principle, scribes could express grammatical relationships and syntax to clarify meaning and be more precise.

There are only a few examples of the use of rebus in the earliest stages of cuneiform (c. 3200 – 3000 BC). Consistent usage of rebus became apparent only after c. 2600 BC. This was the beginning of a true writing system, characterized by a complex combination of word signs and phonograms (signs for vowels and syllables).

By c. 2500 BC, cuneiform (written mostly on clay tablets) was used for a wide variety of religious, political, literary, scholarly and economic documents.

Now the reader of the tablet didn’t have to struggle with the meaning of a pictograph – they could read word-concepts that more clearly conveyed the scribe’s meaning. The number of characters used in writing was reduced from 1000 to 600, to make it simpler.

By the time of the famous priestess-poet Enheduanna (c. 2285 – 2250 BC), cuneiform had become sophisticated enough to convey not only emotional states such as love or betrayal, but also the reasons behind the writer’s experience of these states. Enheduanna wrote a collection of hymns to Inanna in the Sumerian city of Ur, and she is the first author in the world known by name.

Check it out

-

lmfaohasenteredtheblog liked this · 3 weeks ago

lmfaohasenteredtheblog liked this · 3 weeks ago -

my-lingering-soul liked this · 3 weeks ago

my-lingering-soul liked this · 3 weeks ago -

laopfn liked this · 3 weeks ago

laopfn liked this · 3 weeks ago -

vxmpirecrypt liked this · 3 weeks ago

vxmpirecrypt liked this · 3 weeks ago -

truly-eclipse liked this · 3 weeks ago

truly-eclipse liked this · 3 weeks ago -

dipperapplepie liked this · 3 weeks ago

dipperapplepie liked this · 3 weeks ago -

breadcream liked this · 3 weeks ago

breadcream liked this · 3 weeks ago -

shxrii liked this · 3 weeks ago

shxrii liked this · 3 weeks ago -

kingheinrey reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

kingheinrey reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

kingheinrey liked this · 3 weeks ago

kingheinrey liked this · 3 weeks ago -

samidiad liked this · 3 weeks ago

samidiad liked this · 3 weeks ago -

ursileporidae liked this · 3 weeks ago

ursileporidae liked this · 3 weeks ago -

cant-think-of-something-better liked this · 3 weeks ago

cant-think-of-something-better liked this · 3 weeks ago -

ozgin liked this · 3 weeks ago

ozgin liked this · 3 weeks ago -

melon-cream-enmu reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

melon-cream-enmu reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

melon-cream-enmu liked this · 3 weeks ago

melon-cream-enmu liked this · 3 weeks ago -

stiff-little-fingers reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

stiff-little-fingers reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

greiiliss liked this · 3 weeks ago

greiiliss liked this · 3 weeks ago -

greiiliss reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

greiiliss reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

brain-empty-no-thoughts liked this · 3 weeks ago

brain-empty-no-thoughts liked this · 3 weeks ago -

anguishworm reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

anguishworm reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

lic-rine liked this · 3 weeks ago

lic-rine liked this · 3 weeks ago -

ladydorian reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

ladydorian reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

abitchnamedtia liked this · 3 weeks ago

abitchnamedtia liked this · 3 weeks ago -

lladyburd reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

lladyburd reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

animal6 liked this · 3 weeks ago

animal6 liked this · 3 weeks ago -

headknight-oh liked this · 3 weeks ago

headknight-oh liked this · 3 weeks ago -

juanvaldezzzsworld reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

juanvaldezzzsworld reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

juanvaldezzzsworld liked this · 3 weeks ago

juanvaldezzzsworld liked this · 3 weeks ago -

kiwimintlime reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

kiwimintlime reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

xcathenny reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

xcathenny reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

iiamaghoull liked this · 3 weeks ago

iiamaghoull liked this · 3 weeks ago -

yunyanshine liked this · 4 weeks ago

yunyanshine liked this · 4 weeks ago -

ifuckinglovemusic reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

ifuckinglovemusic reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

ifuckinglovemusic liked this · 4 weeks ago

ifuckinglovemusic liked this · 4 weeks ago -

infinitew-olf reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

infinitew-olf reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

cheriebear liked this · 4 weeks ago

cheriebear liked this · 4 weeks ago -

itsdarkrxn reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

itsdarkrxn reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

itsdarkrxn liked this · 4 weeks ago

itsdarkrxn liked this · 4 weeks ago -

danieyells reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

danieyells reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

leathernbangs liked this · 1 month ago

leathernbangs liked this · 1 month ago -

cinemacrypt reblogged this · 1 month ago

cinemacrypt reblogged this · 1 month ago -

thefunksp reblogged this · 1 month ago

thefunksp reblogged this · 1 month ago -

thefunksp liked this · 1 month ago

thefunksp liked this · 1 month ago -

breadkween reblogged this · 1 month ago

breadkween reblogged this · 1 month ago -

breadkween liked this · 1 month ago

breadkween liked this · 1 month ago -

imstuckintime liked this · 1 month ago

imstuckintime liked this · 1 month ago -

worldbadger reblogged this · 1 month ago

worldbadger reblogged this · 1 month ago -

worldbadger liked this · 1 month ago

worldbadger liked this · 1 month ago -

joespinell reblogged this · 1 month ago

joespinell reblogged this · 1 month ago