Como As Estrelas Morrem Quando Caem Num Buraco Negro? - Space Today TV Ep.731

Como As Estrelas Morrem Quando Caem Num Buraco Negro? - Space Today TV Ep.731

Desde quando se lê o primeiro texto sobre buracos negros, se aprende que esses objetos possuem uma força gravitacional imensa, e que nem a luz consegue escapar dele, e se um objeto passar pelo horizonte de eventos, não tem mais volta, ele irá cair e desaparecer.

Mas será que existe mesmo um horizonte de eventos? O que nós lemos e aprendemos foi proposto pela Teoria Geral da Relatividade de Albert Einstein.

Será que ao invés de um buraco negro o que tem ali não é um objeto estranho supermassivo.

Diferente do caso do buraco negro onde existe uma singularidade, essa ideia modificada, diz que esse objeto teria uma superfície rígida, nesse caso um objeto, como uma estrela, ao passar próximo se chocaria com a superfície ao invés de ser engolida.

Um grupo de pesquisadores resolveu então testar qual das duas hipóteses é a mais correta para um buraco negro, e esse teste também funcionou como um grande teste, mais uma vez para a Teoria da Relatividade, pois provaria que existe um horizonte de eventos e que nenhum objeto realmente sobrevive a um buraco negro.

Os astrônomos pensaram o que um telescópio poderia ver caso um objeto sobrevivesse a um buraco negro.

Para fazer a busca eles escolheram buracos negros supermassivos no chamado universo próximo.

Então eles buscaram nos dados de arquivos do telescópio Pan-STARRS, um telescópio de 1.8 metros de diâmetro que pesquisa metade do céu do hemisfério norte, e ele escaneou a mesma área repetidamente num período de 3.5 anos buscando pelos chamados transientes.

Basicamente, coisas que brilham e depois apagam, e os pesquisadores buscavam por assinaturas da luz de uma estrela caindo num buraco negro ou se chocando com uma superfície.

Os astrônomos modelaram tudo isso e sabiam a taxa de estrelas que eles deveriam detectar nesse período de 3.5 anos.

E depois de vasculhar os dados do telescópio eles não descobriram absolutamente nada.

A conclusão, os buracos negros realmente possuem um horizonte de eventos e que o material realmente desaparece, como era realmente esperado.

Os astrônomos querem agora no futuro próximo utilizar o Large Synoptic Survey Telescope que como o Pan-STARRS irá pesquisar o céu repetidas vezes buscando por transientes, mas agora com um diâmetro de 8.4 metros.

More Posts from Carlosalberthreis and Others

Em Dezembro de 2015, a ESA lançou o LISA Pathfinder.

Depois de viajar 1.5 milhão de quilômetros e estacionar no ponto de Lagrange onde ficaria operacional, sua missão científica começou especificamente no dia 1 de Março de 2016.

Mas você conhece o LISA Pathfinder, sabe para que ele serve?

O LISA Pathfinder é um projeto da Agência Espacial Europeia que tem por objetivo provar uma tecnologia. A tecnologia de que é possível manter no espaço, dois cubos idênticos de ouro em queda livre, e não somente isso, mas a queda livre mais precisa já conseguida no espaço. Com as massas em um movimento sujeito apenas pela ação da gravidade, será possível realizar uma missão para medir as ondas gravitacionais do espaço.

Todo mundo deve lembrar que esse ano foi anunciado a detecção pela primeira vez das ondas gravitacionais, pelo LIGO, um experimento feito em Terra com dois equipamentos nos EUA. O ponto fundamental aqui é que as ondas gravitacionais ocorrem em um grande intervalo de frequências, e são necessários diferentes equipamentos para registrá-las.

A frequência das ondas gravitacionais detectadas pelo LIGO está na casa dos 100 Hz, com um experimento no espaço como o LISA será possível detectar ondas gravitacionais com frequência milhões de vezes menor do que essa.

Se vocês se lembram bem, o que causou as ondas gravitacionais detectadas pelo LIGO foi a fusão de dois buracos negros de massas estelares. Os astrônomos agora querem detectar colisões e eventos de objetos maiores, como a fusão de buracos negros supermassivos, eventos esses que geram uma frequência bem menor e só um experimento no espaço poderia detectar.

Os resultados mostram que o LISA Pathfinder conseguiu sim provar essa tecnologia, o LISA conseguiu colocar em queda livre protegido de todas as forças, somente com a gravidade atuando, dois cubos de metal com 46 centímetros de lado, com uma precisão 5 vezes maior do que aquela necessária, demonstrando que é sim possível realizar esse tipo de experimento no espaço.

Os resultados foram publicados na revista especializada Physical Review Letters e está animando os cientistas em todo o mundo, pois esses resultados superam em muito as expectativas mais otimistas sobre os resultados do LISA Pathfinder.

O LISA Patfinder é o início de um projeto muito mais ambicioso, o LISA, um sistema de detecção de ondas gravitacionais, que usará 3 naves, separadas por uma distância de 5 milhões de quilômetros entre elas e cada uma delas com cubos em queda livre, assim estará montado o detector de ondas gravitacionais que é o sonho dos astrônomos.

As ondas gravitacionais começaram a pouco a transformar a astronomia, nos dando a chance de conhecer o universo de um novo ponto de vista. E o LISA Pathfinder deu o primeiro passo, com sucesso para se detectar as ondas gravitacionais de baixa frequência do espaço.

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KJR4-NP0kA)

What’s Up - February 2018

What’s Up For February?

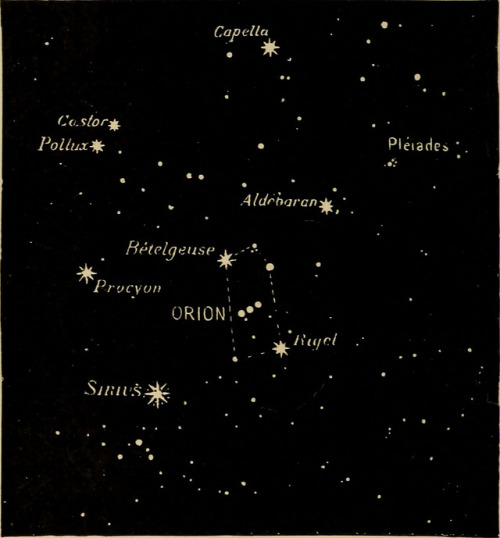

This month, in honor of Valentine’s Day, we’ll focus on celestial star pairs and constellation couples.

Let’s look at some celestial pairs!

The constellations Perseus and Andromeda are easy to see high overhead this month.

According to lore, the warrior Perseus spotted a beautiful woman–Andromeda–chained to a seaside rock. After battling a sea serpent, he rescued her.

As a reward, her parents Cepheus and Cassiopeia allowed Perseus to marry Andromeda.

The great hunter Orion fell in love with seven sisters, the Pleiades, and pursued them for a long time. Eventually Zeus turned both Orion and the Pleiades into stars.

Orion is easy to find. Draw an imaginary line through his belt stars to the Pleiades, and watch him chase them across the sky forever.

A pair of star clusters is visible on February nights. The Perseus Double Cluster is high in the sky near Andromeda’s parents Cepheus and Cassiopeia.

Through binoculars you can see dozens of stars in each cluster. Actually, there are more than 300 blue-white supergiant stars in each of the clusters.

There are some colorful star pairs, some visible just by looking up and some requiring a telescope. Gemini’s twins, the brothers Pollux and Castor, are easy to see without aid.

Orion’s westernmost, or right, knee, Rigel, has a faint companion. The companion, Rigel B, is 500 times fainter than the super-giant Rigel and is visible only with a telescope.

Orion’s westernmost belt star, Mintaka, has a pretty companion. You’ll need a telescope.

Finally, the moon pairs up with the Pleiades on the 22nd and with Pollux and Castor on the 26th.

Watch the full What’s Up for February Video:

There are so many sights to see in the sky. To stay informed, subscribe to our What’s Up video series on Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

This is not just an incredible view of Earth, it’s also a fantastic illustration of the terminator. (No not that one!) The terminator is the moving line that separates the day side from the dark night side of a planetary body. From this vantage point you can make out the gradual transition to darkness that is experienced as twilight on the surface. This image was captured on Aug. 31 by astronaut Jeff Williams (@Astro_Jeff) while on board the ISS.

Incoming! We’ve Got Science from Jupiter!

Our Juno spacecraft has just released some exciting new science from its first close flyby of Jupiter!

In case you don’t know, the Juno spacecraft entered orbit around the gas giant on July 4, 2016…about a year ago. Since then, it has been collecting data and images from this unique vantage point.

Juno is in a polar orbit around Jupiter, which means that the majority of each orbit is spent well away from the gas giant. But once every 53 days its trajectory approaches Jupiter from above its north pole, where it begins a close two-hour transit flying north to south with its eight science instruments collecting data and its JunoCam camera snapping pictures.

Space Fact: The download of six megabytes of data collected during the two-hour transit can take one-and-a-half days!

Juno and her cloud-piercing science instruments are helping us get a better understanding of the processes happening on Jupiter. These new results portray the planet as a complex, gigantic, turbulent world that we still need to study and unravel its mysteries.

So what did this first science flyby tell us? Let’s break it down…

1. Tumultuous Cyclones

Juno’s imager, JunoCam, has showed us that both of Jupiter’s poles are covered in tumultuous cyclones and anticyclone storms, densely clustered and rubbing together. Some of these storms as large as Earth!

These storms are still puzzling. We’re still not exactly sure how they formed or how they interact with each other. Future close flybys will help us better understand these mysterious cyclones.

Seen above, waves of clouds (at 37.8 degrees latitude) dominate this three-dimensional Jovian cloudscape. JunoCam obtained this enhanced-color picture on May 19, 2017, at 5:50 UTC from an altitude of 5,500 miles (8,900 kilometers). Details as small as 4 miles (6 kilometers) across can be identified in this image.

An even closer view of the same image shows small bright high clouds that are about 16 miles (25 kilometers) across and in some areas appear to form “squall lines” (a narrow band of high winds and storms associated with a cold front). On Jupiter, clouds this high are almost certainly comprised of water and/or ammonia ice.

2. Jupiter’s Atmosphere

Juno’s Microwave Radiometer is an instrument that samples the thermal microwave radiation from Jupiter’s atmosphere from the tops of the ammonia clouds to deep within its atmosphere.

Data from this instrument suggest that the ammonia is quite variable and continues to increase as far down as we can see with MWR, which is a few hundred kilometers. In the cut-out image below, orange signifies high ammonia abundance and blue signifies low ammonia abundance. Jupiter appears to have a band around its equator high in ammonia abundance, with a column shown in orange.

Why does this ammonia matter? Well, ammonia is a good tracer of other relatively rare gases and fluids in the atmosphere…like water. Understanding the relative abundances of these materials helps us have a better idea of how and when Jupiter formed in the early solar system.

This instrument has also given us more information about Jupiter’s iconic belts and zones. Data suggest that the belt near Jupiter’s equator penetrates all the way down, while the belts and zones at other latitudes seem to evolve to other structures.

3. Stronger-Than-Expected Magnetic Field

Prior to Juno, it was known that Jupiter had the most intense magnetic field in the solar system…but measurements from Juno’s magnetometer investigation (MAG) indicate that the gas giant’s magnetic field is even stronger than models expected, and more irregular in shape.

At 7.766 Gauss, it is about 10 times stronger than the strongest magnetic field found on Earth! What is Gauss? Magnetic field strengths are measured in units called Gauss or Teslas. A magnetic field with a strength of 10,000 Gauss also has a strength of 1 Tesla.

Juno is giving us a unique view of the magnetic field close to Jupiter that we’ve never had before. For example, data from the spacecraft (displayed in the graphic above) suggests that the planet’s magnetic field is “lumpy”, meaning its stronger in some places and weaker in others. This uneven distribution suggests that the field might be generated by dynamo action (where the motion of electrically conducting fluid creates a self-sustaining magnetic field) closer to the surface, above the layer of metallic hydrogen. Juno’s orbital track is illustrated with the black curve.

4. Sounds of Jupiter

Juno also observed plasma wave signals from Jupiter’s ionosphere. This movie shows results from Juno’s radio wave detector that were recorded while it passed close to Jupiter. Waves in the plasma (the charged gas) in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter have different frequencies that depend on the types of ions present, and their densities.

Mapping out these ions in the jovian system helps us understand how the upper atmosphere works including the aurora. Beyond the visual representation of the data, the data have been made into sounds where the frequencies and playback speed have been shifted to be audible to human ears.

5. Jovian “Southern Lights”

The complexity and richness of Jupiter’s “southern lights” (also known as auroras) are on display in this animation of false-color maps from our Juno spacecraft. Auroras result when energetic electrons from the magnetosphere crash into the molecular hydrogen in the Jovian upper atmosphere. The data for this animation were obtained by Juno’s Ultraviolet Spectrograph.

During Juno’s next flyby on July 11, the spacecraft will fly directly over one of the most iconic features in the entire solar system – one that every school kid knows – Jupiter’s Great Red Spot! If anybody is going to get to the bottom of what is going on below those mammoth swirling crimson cloud tops, it’s Juno.

Stay updated on all things Juno and Jupiter by following along on social media: Twitter | Facebook | YouTube | Tumblr

Learn more about the Juno spacecraft and its mission at Jupiter HERE.

O absurdo do Brasil…ah é mesmo, tem o legado da copa e nem se compara com as descobertas da New Horizons.

Solar System: Things to Know This Week

Jupiter, our solar system’s largest planet, is making a good showing in night skies this month. Look for it in the southeast in each evening. With binoculars, you may be able to see the planet’s four largest moons. Here are some need-to-know facts about the King of the Planets.

1. The Biggest Planet:

With a radius of 43,440.7 miles (69,911 kilometers), Jupiter is 11 times wider than Earth. If Earth were the size of a nickel, Jupiter would be about as big as a basketball.

2. Fifth in Line

Jupiter orbits our sun, and is the fifth planet from the sun at a distance of about 484 million miles (778 million km) or 5.2 Astronomical Units (AU). Earth is one AU from the sun.

3. Short Day / Long Year

One day on Jupiter takes about 10 hours (the time it takes for Jupiter to rotate or spin once). Jupiter makes a complete orbit around the sun (a year in Jovian time) in about 12 Earth years (4,333 Earth days).

4. What’s Inside?

Jupiter is a gas-giant planet without a solid surface. However, the planet may have a solid, inner core about the size of Earth.

5. Atmosphere

Jupiter’s atmosphere is made up mostly of hydrogen (H2) and helium (He).

6. Many Moons

Jupiter has 53 known moons, with an additional 14 moons awaiting confirmation of their discovery — a total of 67 moons.

7. Ringed World

All four giant planets in our solar system have ring systems and Jupiter is no exception. Its faint ring system was discovered in 1979 by the Voyager 1 mission.

8. Exploring Jupiter:

Many missions have visited Jupiter and its system of moons. The Juno spacecraft is currently orbiting Jupiter.

9. Ingredients for Life?

Jupiter cannot support life as we know it. However, some of Jupiter’s moons have oceans underneath their crusts that might support life.

10. Did You Know?

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a gigantic storm (about the size of Earth) that has been raging for hundreds of years.

Discover more lists of 10 things to know about our solar system HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Em um final de tarde próximo à igreja São Benedito, observei no horizonte este cenário. 🌅

Aconteceu neste dia um pôr do sol típico da amazônia e também uma conjunção entre a Lua e os planetas Vênus e Mercúrio.

Um detalhe que eu enfatizei foi esta árvore, que no início fiquei pensativo, se eu registrava ou não estas imagens. Após algum tempo, decidi então tirar umas fotos, pois, lembrei do seguinte pensamento:

💭 Tudo o que enxergamos ao nosso redor, nunca mais vai se repetir. É um evento único. Que ficarão em nossas memórias.

Meses depois, soube que esta árvore, talvez do tipo flamboiã ou similares, não estava mais nesse local. Pois, iniciaram obras de contenção de erosão na orla onde esta árvore ficava.

Com isso, talvez foram os últimos registros desta árvore ainda viva. 🌳

📅 Data de registro: 5 de agosto de 2024 às 18:22

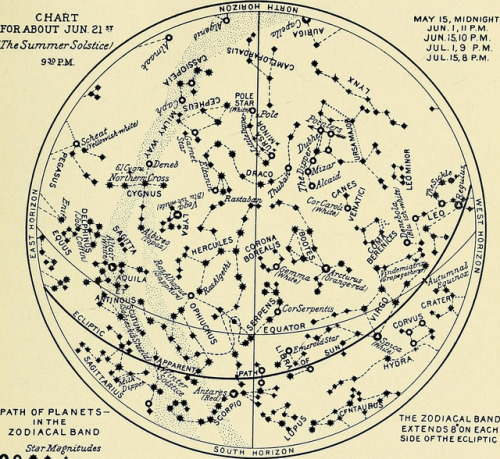

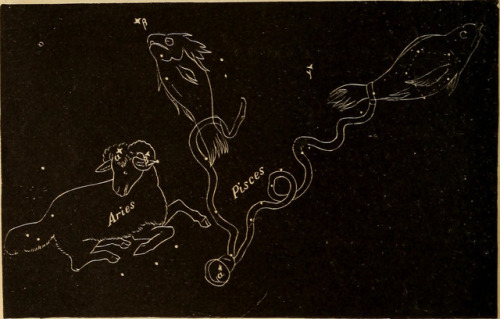

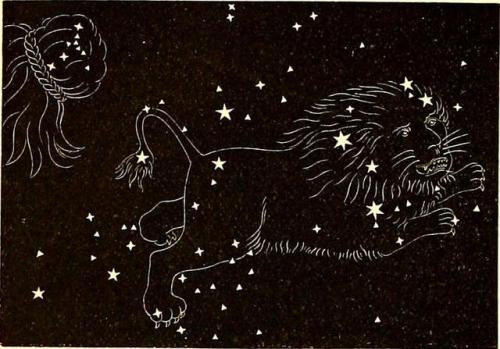

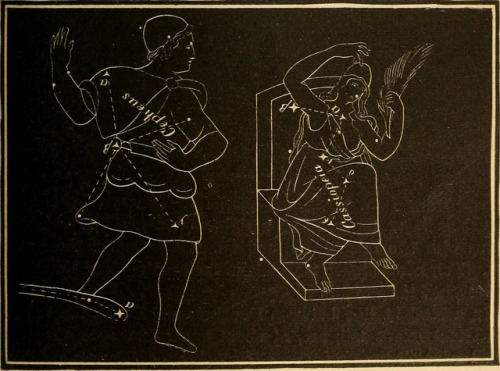

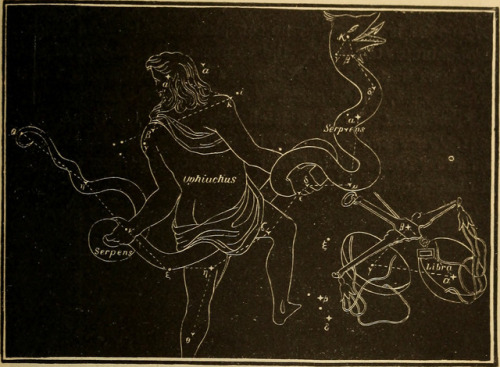

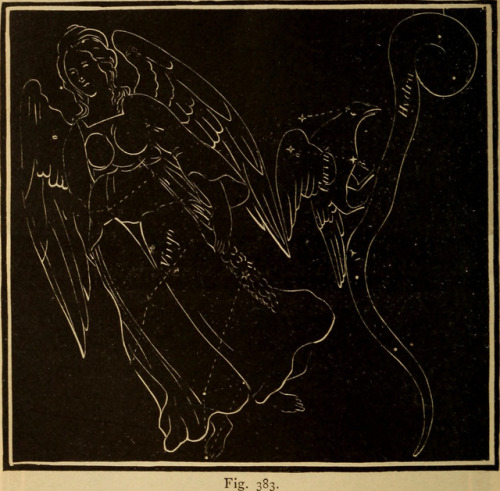

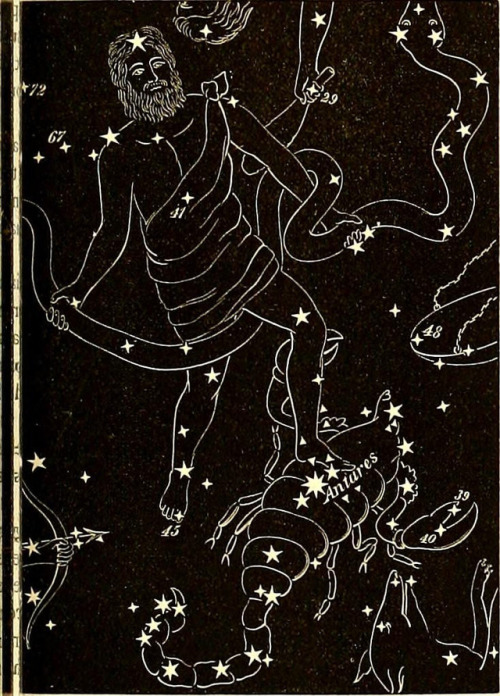

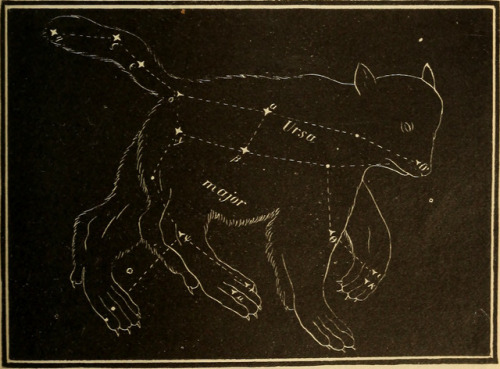

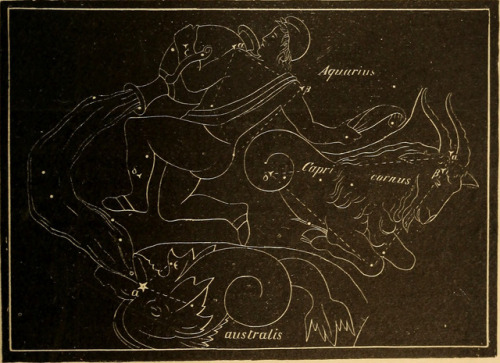

Constellations

A constellation is a group of stars that are considered to form imaginary outlines or meaningful patterns on the celestial sphere, typically representing animals, mythological people or gods, mythological creatures, or manufactured devices. The 88 modern constellations are formally defined regions of the sky together covering the entire celestial sphere.

Origins for the earliest constellations likely goes back to prehistory, whose now unknown creators collectively used them to related important stories of either their beliefs, experiences, creation or mythology. As such, different cultures and countries often adopted their own set of constellations outlines, some that persisted into the early 20th Century. Adoption of numerous constellations have significantly changed throughout the centuries. Many have varied in size or shape, while some became popular then dropped into obscurity. Others were traditionally used only by various cultures or single nations.

The Western-traditional constellations are the forty-eight Greek classical patterns, as stated in both Aratus’s work Phenomena or Ptolemy’s Almagest — though their existence probably predates these constellation names by several centuries. Newer constellations in the far southern sky were added much later during the 15th to mid-18th century, when European explorers began travelling to the southern hemisphere. Twelve important constellations are assigned to the zodiac, where the Sun, Moon, and planets all follow the ecliptic. The origins of the zodiac probably date back into prehistory, whose astrological divisions became prominent around 400BCE within Babylonian or Chaldean astronomy.

In 1928, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) ratified and recognized 88 modern constellations, with contiguous boundaries defined by right ascension and declination. Therefore, any given point in a celestial coordinate system lies in one of the modern constellations. Some astronomical naming systems give the constellation where a given celestial object is found along with a designation in order to convey an approximate idea of its location in the sky. e.g. The Flamsteed designation for bright stars consists of a number and the genitive form of the constellation name.

source

images

-

carlosalberthreis reblogged this · 7 years ago

carlosalberthreis reblogged this · 7 years ago -

carlosalberthreis liked this · 7 years ago

carlosalberthreis liked this · 7 years ago -

astroimages reblogged this · 7 years ago

astroimages reblogged this · 7 years ago