Ten Interesting Facts About Mercury

Ten Interesting facts about Mercury

Mercury is the closest planet to the sun. As such, it circles the sun faster than all the other planets, which is why Romans named it after their swift-footed messenger god. He is the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, messages, communication (including divination), travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves; he also serves as the guide of souls to the underworld

Like Venus, Mercury orbits the Sun within Earth’s orbit as an inferior planet, and never exceeds 28° away from the Sun. When viewed from Earth, this proximity to the Sun means the planet can only be seen near the western or eastern horizon during the early evening or early morning. At this time it may appear as a bright star-like object, but is often far more difficult to observe than Venus. The planet telescopically displays the complete range of phases, similar to Venus and the Moon, as it moves in its inner orbit relative to Earth, which reoccurs over the so-called synodic period approximately every 116 days.

Mercury’s axis has the smallest tilt of any of the Solar System’s planets (about 1⁄30 degree). Its orbital eccentricity is the largest of all known planets in the Solar System; at perihelion, Mercury’s distance from the Sun is only about two-thirds (or 66%) of its distance at aphelion.

Its orbital period around the Sun of 87.97 days is the shortest of all the planets in the Solar System. A sidereal day (the period of rotation) lasts about 58.7 Earth days.

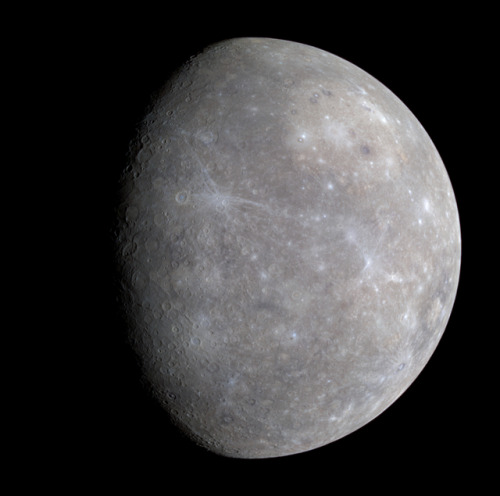

Mercury’s surface appears heavily cratered and is similar in appearance to the Moon’s, indicating that it has been geologically inactive for billions of years. Having almost no atmosphere to retain heat, it has surface temperatures that vary diurnally more than on any other planet in the Solar System, ranging from 100 K (−173 °C; −280 °F) at night to 700 K (427 °C; 800 °F) during the day across the equatorial regions. The polar regions are constantly below 180 K (−93 °C; −136 °F). The planet has no known natural satellites.

Unlike many other planets which “self-heal” through natural geological processes, the surface of Mercury is covered in craters. These are caused by numerous encounters with asteroids and comets. Most Mercurian craters are named after famous writers and artists. Any crater larger than 250 kilometres in diameter is referred to as a Basin.

The largest known crater is Caloris Basin, with a diameter of 1,550 km. The impact that created the Caloris Basin was so powerful that it caused lava eruptions and left a concentric ring over 2 km tall surrounding the impact crater.

Two spacecraft have visited Mercury: Mariner 10 flew by in 1974 and 1975; and MESSENGER, launched in 2004, orbited Mercury over 4,000 times in four years before exhausting its fuel and crashing into the planet’s surface on April 30, 2015.

It is the smallest planet in the Solar System, with an equatorial radius of 2,439.7 kilometres (1,516.0 mi). Mercury is also smaller—albeit more massive—than the largestnatural satellites in the Solar System, Ganymede and Titan.

As if Mercury isn’t small enough, it not only shrank in its past but is continuing to shrink today. The tiny planet is made up of a single continental plate over a cooling iron core. As the core cools, it solidifies, reducing the planet’s volume and causing it to shrink. The process crumpled the surface, creating lobe-shaped scarps or cliffs, some hundreds of miles long and soaring up to a mile high, as well as Mercury’s “Great Valley,” which at about 620 miles long, 250 miles wide and 2 miles deep (1,000 by 400 by 3.2 km) is larger than Arizona’s famous Grand Canyon and deeper than the Great Rift Valley in East Africa.

The first telescopic observations of Mercury were made by Galileo in the early 17th century. Although he observed phases when he looked at Venus, his telescope was not powerful enough to see the phases of Mercury.

source 1

source 2

source 3

images: Joseph Brimacombe, NASA/JPL, Wikimedia Commons

More Posts from Carlosalberthreis and Others

Conjunction: Mars, Venus and Moon

by Stefan Grießinger

The Moon in Motion

Happy New Year! And happy supermoon! Tonight, the Moon will appear extra big and bright to welcome us into 2018 – about 6% bigger and 14% brighter than the average full Moon. And how do we know that? Well, each fall, our science visualizer Ernie Wright uses data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) to render over a quarter of a million images of the Moon. He combines these images into an interactive visualization, Moon Phase and Libration, which depicts the Moon at every day and hour for the coming year.

Want to see what the Moon will look like on your birthday this year? Just put in the date, and even the hour (in Universal Time) you were born to see your birthday Moon.

Our Moon is quite dynamic. In addition to Moon phases, our Moon appears to get bigger and smaller throughout the year, and it wobbles! Or at least it looks that way to us on Earth. This wobbling is called libration, from the Latin for ‘balance scale’ (libra). Wright relies on LRO maps of the Moon and NASA orbit calculations to create the most accurate depiction of the 6 ways our Moon moves from our perspective.

1. Phases

The Moon phases we see on Earth are caused by the changing positions of the Earth and Moon relative to the Sun. The Sun always illuminates half of the Moon, but we see changing shapes as the Moon revolves around the Earth. Wright uses a software library called SPICE to calculate the position and orientation of the Moon and Earth at every moment of the year. With his visualization, you can input any day and time of the year and see what the Moon will look like!

2. Shape of the Moon

Check out that crater detail! The Moon is not a smooth sphere. It’s covered in mountains and valleys and thanks to LRO, we know the shape of the Moon better than any other celestial body in the universe. To get the most accurate depiction possible of where the sunlight falls on the lunar surface throughout the month, Wright uses the same graphics software used by Hollywood design studios, including Pixar, and a method called ‘raytracing’ to calculate the intricate patterns of light and shadow on the Moon’s surface, and he checks the accuracy of his renders against photographs of the Moon he takes through his own telescope.

3. Apparent Size

The Moon Phase and Libration visualization shows you the apparent size of the Moon. The Moon’s orbit is elliptical, instead of circular - so sometimes it is closer to the Earth and sometimes it is farther. You’ve probably heard the term “supermoon.” This describes a full Moon at or near perigee (the point when the Moon is closest to the Earth in its orbit). A supermoon can appear up to 14% bigger and brighter than a full Moon at apogee (the point when the Moon is farthest from the Earth in its orbit).

Our supermoon tonight is a full Moon very close to perigee, and will appear to be about 14% bigger than the July 27 full Moon, the smallest full Moon of 2018, occurring at apogee. Input those dates into the Moon Phase and Libration visualization to see this difference in apparent size!

4. East-West Libration

Over a month, the Moon appears to nod, twist, and roll. The east-west motion, called ‘libration in longitude’, is another effect of the Moon’s elliptical orbital path. As the Moon travels around the Earth, it goes faster or slower, depending on how close it is to the Earth. When the Moon gets close to the Earth, it speeds up thanks to an additional pull from Earth’s gravity. Then it slows down, when it’s farther from the Earth. While this speed in orbital motion changes, the rotational speed of the Moon stays constant.

This means that when the Moon moves faster around the Earth, the Moon itself doesn’t rotate quite enough to keep the same exact side facing us and we get to see a little more of the eastern side of the Moon. When the Moon moves more slowly around the Earth, its rotation gets a little ahead, and we see a bit more of its western side.

5. North-South Libration

The Moon also appears to nod, as if it were saying “yes,” a motion called ‘libration in latitude’. This is caused by the 5 degree tilt of the Moon’s orbit around the Earth. Sometimes the Moon is above the Earth’s northern hemisphere and sometimes it’s below the Earth’s southern hemisphere, and this lets us occasionally see slightly more of the northern or southern hemispheres of the Moon!

6. Axis Angle

Finally, the Moon appears to tilt back and forth like a metronome. The tilt of the Moon’s orbit contributes to this, but it’s mostly because of the 23.5 degree tilt of our own observing platform, the Earth. Imagine standing sideways on a ramp. Look left, and the ramp slopes up. Look right and the ramp slopes down.

Now look in front of you. The horizon will look higher on the right, lower on the left (try this by tilting your head left). But if you turn around, the horizon appears to tilt the opposite way (tilt your head to the right). The tilted platform of the Earth works the same way as we watch the Moon. Every two weeks we have to look in the opposite direction to see the Moon, and the ground beneath our feet is then tilted the opposite way as well.

So put this all together, and you get this:

Beautiful isn’t it? See if you can notice these phenomena when you observe the Moon. And keep coming back all year to check on the Moon’s changing appearance and help plan your observing sessions.

Follow @NASAMoon on Twitter to keep up with the latest lunar updates.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

A China lançou com sucesso um satélite de comunicação lunar, desenvolvido para ajudar na missão histórica que o país lançará ainda em 2018 de colocar um lander e um rover no lado distante (escuro, oculto) da Lua. Além de servir como relay de dados, esse satélite ainda fará experimentos astronômicos.

O satélite de relay da Chang’e-4, está sendo acompanhado por dois microssatélites, e tudo isso foi lançado a bordo de um foguete Long March 4C direto do Xichang Satellite Launch Centre, às 18:28 hora de Brasília, desse domingo, dia 20 de Maio de 2018.

A sonda foi inserida com sucesso na órbita de transferência lunar e se separou do estágio superior de seu foguete. O China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, o CASC, o principal contratante para o programa espacial, confirmou o sucesso em menos de uma hora após o lançamento.

Chamado de Queqiao, o satélite está agora numa jornada de 8 a 9 dias até o segundo ponto de Lagrange do sistema Terra-Lua, conhecido como E-M L2, que fica entre 60 e 80 mil quilômetros além da Lua, ou seja, a quase meio milhão de quilômetros da Terra.

O principal objetivo da missão é fornecer um meio de comunicação para as operações de um lander e de um rover lunar que serão colocados no lado distante da Lua, algo que nunca foi testado antes.

Como a Lua é travada gravitacionalmente com a Terra, esse lado distante, nunca está voltado para a Terra. Pousar missões ali, requer um sistema de comunicação com base nesses satélites que fazem o relay dos dados e que sempre estarão com as estações em Terra e com o lander e rover na sua linha de visada.

O ponto E-M L2 que é gravitacionalmente estável irá fornecer essa posição e a órbita adequada para o satélite realizar a sua função.

Queqiao, irá fazer um sobrevoo lunar para ser lançado para seu destino além da Lua e usará seu próprio sistema de propulsão para entrar numa órbita halo ao redor do ponto de Lagrange.

Uma vez no seu ponto, o satélite de 448 kg CAST100, desenvolvido pela China Academy of Space Technology, a CAST, uma empresa fabricante de sondas que trabalha para o CASC, irá testar sua antena parabólica de 4.2 metros de diâmetro e todas as funções antes que a missão levando o lander e o rover chegue na Lua.

O satélite enviado hoje, marca a quinta missão lunar chinesa, contando os dois módulos orbitais, Chang’e-1 em 2007, o Chang’e-2 em 2010, o rover e lander lunar da missão Chang’e-3 de 2013, e uma missão teste de retorno de amostras da Lua em 2014.

Em 2019, a China irá lançar a missão Chang’e-5 para coletar 2 kg de amostras do solo lunar e mandar de volta para Terra.

O lançamento desse domingo, dia 20 de Maio de 2018, marcou o décimo quinto lançamento da China em 2018, lembrando que a China pretende fazer cerca de 40 lançamentos nesse ano, o que dá quase 1 lançamento por semana.

Além de ajudar nas missões que pousarão na Lua, o satélite também irá usar 3 antenas de 5 metros de diâmetro de monopólio que serão usadas para realizar uma astronomia de frequência muito baixa que é impossível de ser feita na Terra, devido à atmosfera do nosso planeta.

A Netherlands-China Low frequency Explorer, ou NCLE, desenvolvido pela Readbound University, e outros, irá tentar detectar um sinal de baixa frequência proveniente da era negra do universo, algo que aconteceu poucas centenas de milhões de anos após o Big Bang, antes das primeiras estrelas brilharem.

Outros objetivos, disse Marc Klein Wolt, da Readbound University, e líder de projeto do NCLE, incluem, pesquisas do Sistema Solar nessas frequências, além de agir como uma base para futuras missões.

Perguntado se o NCLE poderia também, apesar de não ser o objetivo científico da equipe, contribuir para a pesquisa por inteligência extraterrestre, Klein Wolt, disse que, “em princípio poderia, já que nós estamos abrindo uma nova janela para o universo, mas eu não estou esperando encontrar qualquer ET”.

Dois microssatélites, o Longjiang-1 e 2, também estavam a bordo do foguete chinês, e tentarão entrar numa órbita lunar altamente elíptica para realizar suas tarefas astronômicas.

Os satélites pesando 45 kg e com dimensões de 50x50x40 cm, desenvolvidos pelo Harbin Institute of Technology, o HIT, em Heilongjiang , usará antenas de 1 metro para testar radioastronomia de baixa frequência e um tipo de interferometria baseada no espaço.

Principalmente usado como uma verificação técnica para futuras missões, o par de pequenos satélites também está levando experimentos de rádio amadores, além de uma pequena câmera óptica desenvolvida pela Arábia Saudita.

A Chang’e-4 era considerada primeiramente como uma missão reserva da Chang’e-3 que levou o rover Yutu para tocar o solo do Mare Imbrium em 2013.

Como a missão foi realizada com sucesso, apesar de uma falha mecânica no Yutu, a sonda Chang’e-4 foi então confirmada como sendo a missão para o lado distante da Lua.

O alvo para que a Chang’e-4 pouse na Lua é dentro da cratera Von Kármán, que fica na Bacia Aitken do Polo Sul, uma área intrigante do ponto de vista científico, que pode oferecer uma grande ideia sobre a história e sobre o desenvolvimento tanto da Lua como do nosso Sistema Solar.

As câmeras na Chang’e-3 mandaram imagens espetaculares do Mare Imbrium, e o mesmo espera-se da Chang’e-4. A Chang’e-3 fez inúmeras descobertas com seus instrumentos, incluindo múltiplas camadas distintas na superfície, sugerindo que a Lua teve uma história geológica mais complexa do que se pensava anteriormente.

Imaginem o que uma missão no lado distante da Lua não pode nos revelar.

Fonte:

https://gbtimes.com/china-launches-queqiao-relay-satellite-to-support-change-4-lunar-far-side-landing-mission

O que vamos ter em dezembro de 2017!

What's Up - December 2017

What’s Up For December? Geminid and Ursid meteor showers & winter constellations!

This month hosts the best meteor shower of the year and the brightest stars in familiar constellations.

The Geminds peak on the morning of the 14th, and are active from December 4th through the 17th. The peak lasts for a full 24 hours, meaning more worldwide meteor watchers will get to see this spectacle.

Expect to see up to 120 meteors per hour between midnight and 4 a.m. but only from a dark sky. You’ll see fewer after moonrise at 3:30 a.m. local time.

In the southern hemisphere, you won’t see as many, perhaps 10-20 per hour, because the radiant never rises above the horizon.

Take a moment to enjoy the circle of constellations and their brightest stars around Gemini this month.

Find yellow Capella in the constellation Auriga.

Next-going clockwise–at 1 o'clock find Taurus and bright reddish Aldebaran, plus the Pleiades.

At two, familiar Orion, with red Betelguese, blue-white Rigel, and the three famous belt stars in-between the two.

Next comes Leo, and its white lionhearted star, Regulus at 7 o'clock.

Another familiar constellation Ursa Major completes the view at 9 o'clock.

There’s a second meteor shower in December, the Ursids, radiating from Ursa Minor, the Little Dipper. If December 22nd and the morning of December 23rd are clear where you are, have a look at the Little Dipper’s bowl, and you might see about ten meteors per hour. Watch the full What’s Up for December Video:

There are so many sights to see in the sky. To stay informed, subscribe to our What’s Up video series on Facebook. Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

The Faint Rings of Uranus

Taken in January, 1986 by Voyager 2. Uranus assembled using orange, simulated green, and violet light. The rings were taken in clear (white) light, but colored red here.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Kevin M. Gill

NGC 6960 (Western Veil nebula) & Horsehead Nebula and the Flame Nebula

by David Wills

Reinventing the Wheel

Planning a trip to the Moon? Mars? You’re going to need good tires…

Exploration requires mobility. And whether you’re on Earth or as far away as the Moon or Mars, you need good tires to get your vehicle from one place to another. Our decades-long work developing tires for space exploration has led to new game-changing designs and materials. Yes, we’re reinventing the wheel—here’s why.

Wheels on the Moon

Early tire designs were focused on moving hardware and astronauts across the lunar surface. The last NASA vehicle to visit the Moon was the Lunar Roving Vehicle during our Apollo missions. The vehicle used four large flexible wire mesh wheels with stiff inner frames. We used these Apollo era tires as the inspiration for new designs using newer materials and technology to better function on a lunar surface.

Up springs a new idea

During the mid-2000s, we worked with industry partner Goodyear to develop the Spring Tire, an airless compliant tire that consists of several hundred coiled steel wires woven into a flexible mesh, giving the tires the ability to support high loads while also conforming to the terrain. The Spring Tire has been proven to generate very good traction and durability in soft sand and on rocks.

Spring Tires for Mars

A little over a year after the Mars Curiosity Rover landed on Mars, engineers began to notice significant wheel damage in 2013 due to the unexpectedly harsh terrain. That’s when engineers began developing new Spring Tire prototypes to determine if they would be a new and better solution for exploration rovers on Mars.

In order for Spring Tires to go the distance on Martian terrain, new materials were required. Enter nickel titanium, a shape memory alloy with amazing capabilities that allow the tire to deform down to the axle and return to its original shape.

These tires can take a lickin’

After building the shape memory alloy tire, Glenn engineers sent it to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Mars Life Test Facility. It performed impressively on the punishing track.

Why reinvent the wheel? It’s worth it.

New, high performing tires would allow lunar and Mars rovers to explore greater regions of the surface than currently possible. They conform to the terrain and do not sink as much as rigid wheels, allowing them to carry heavier payloads for the same given mass and volume. Also, because they absorb energy from impacts at moderate to high speeds, there is potential for use on crewed exploration vehicles which are expected to move at speeds significantly higher than the current Mars rovers.

Airless tires on Earth

Maybe. Recently, engineers and materials scientists have been testing a spinoff tire version that would work on cars and trucks on Earth. Stay tuned as we continue to push the boundaries on traditional concepts for exploring our world and beyond.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

-

krya00 liked this · 6 months ago

krya00 liked this · 6 months ago -

thedoll liked this · 2 years ago

thedoll liked this · 2 years ago -

neptune-orbits liked this · 2 years ago

neptune-orbits liked this · 2 years ago -

poynter66 liked this · 2 years ago

poynter66 liked this · 2 years ago -

motomamiblog liked this · 2 years ago

motomamiblog liked this · 2 years ago -

ewigenschlaf788 liked this · 3 years ago

ewigenschlaf788 liked this · 3 years ago -

announmmmmys liked this · 4 years ago

announmmmmys liked this · 4 years ago -

manaalficient liked this · 4 years ago

manaalficient liked this · 4 years ago -

fireball763 reblogged this · 4 years ago

fireball763 reblogged this · 4 years ago -

fireball763 liked this · 4 years ago

fireball763 liked this · 4 years ago -

canatrix liked this · 4 years ago

canatrix liked this · 4 years ago -

driftinhome liked this · 4 years ago

driftinhome liked this · 4 years ago -

beyazsokakkedisi liked this · 5 years ago

beyazsokakkedisi liked this · 5 years ago -

malletboy337 liked this · 5 years ago

malletboy337 liked this · 5 years ago -

heyyyitsmair liked this · 5 years ago

heyyyitsmair liked this · 5 years ago -

dogsiskela liked this · 5 years ago

dogsiskela liked this · 5 years ago -

ameliecameli liked this · 5 years ago

ameliecameli liked this · 5 years ago -

maleee196-blog liked this · 5 years ago

maleee196-blog liked this · 5 years ago -

dedalodeemociones1 reblogged this · 5 years ago

dedalodeemociones1 reblogged this · 5 years ago -

luhverswift liked this · 5 years ago

luhverswift liked this · 5 years ago -

92sbaby liked this · 5 years ago

92sbaby liked this · 5 years ago -

tourharry reblogged this · 5 years ago

tourharry reblogged this · 5 years ago -

quest4space reblogged this · 5 years ago

quest4space reblogged this · 5 years ago -

shejustcalledmeafish liked this · 5 years ago

shejustcalledmeafish liked this · 5 years ago -

sneaky-witch-thief reblogged this · 5 years ago

sneaky-witch-thief reblogged this · 5 years ago -

bizertino liked this · 6 years ago

bizertino liked this · 6 years ago -

ultimateuselesness reblogged this · 6 years ago

ultimateuselesness reblogged this · 6 years ago -

ironfarmstudentdreamer-blog liked this · 6 years ago

ironfarmstudentdreamer-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

sleepinclined liked this · 6 years ago

sleepinclined liked this · 6 years ago -

vythodias liked this · 6 years ago

vythodias liked this · 6 years ago -

bythebrea reblogged this · 6 years ago

bythebrea reblogged this · 6 years ago -

whitecatnatalie reblogged this · 6 years ago

whitecatnatalie reblogged this · 6 years ago -

whitecatnatalie liked this · 6 years ago

whitecatnatalie liked this · 6 years ago