Latest Posts by gothphrodite - Page 2

collector of small and meaningful objects (with no inherent use other than to make the heart glow a little softer)

I loved Dita Von Teese’s old house, but now she’s bought a larger, Tudor style home and decorated it very differently. (She still has her vintage taxidermy collection, though.)

This is the entrance hall. Originally, she collected taxidermied birds.

This was her old living room- Art Deco furniture, and the designer picked out the beautiful flocked teal wallpaper.

This is the new living room. Check out that tiger- the crown is a nice touch. Dita says all the taxidermy is at least 75 yrs. old.

She went bright red oriental in the dining room.

This was her old kitchen- retro & pink.

The new kitchen- she wanted it to look like a woman’s kitchen. Well, she’s got a teal Aga stove.

Rosy red velvet sitting room.

The old dressing table had a sultry glamour.

The new.

The old bedroom.

The new.

A collection of vintage hats adorned her old dressing room.

The new one is a converted closet.

This is the shoe room.

It has a lovely bath that matches the style of the house, but it’s not her usual Hollywood style. I don’t know, I just like the old house better.

https://www.architecturaldigest.com/

Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, December 11, 1918

can’t wait til I’m released from captivity into the wild and immediately get carried off by an eagle

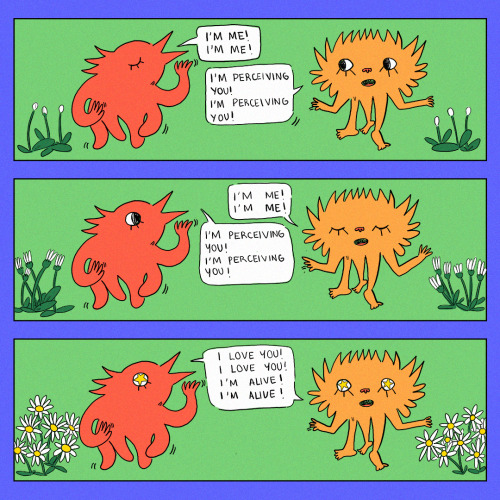

As opposed to that quote about “the horrifying ordeal of being known,” do y’all ever feel so positively UNKNOWN and UNSEEN that it frightens you? Like there’s a self that you feel on the inside, and you believe to be “you,” but it seems like nobody else sees that version of you? And they’re interacting with someone that isn’t you but a projection of their experience of you? What’s more, perhaps nobody will ever know your true essence and you will die without ever being fully realized????? I’m only two beers in honestly

Percy Shelley memorial at Oxford to depict his body washed up on the shore after drowning. Percy attended Oxford for a short time and was later expelled for writing The Necessity of Atheism.

“You don’t know anyone at the party, so you don’t want to go. You don’t like cottage cheese, so you haven’t eaten it in years. This is your choice, of course, but don’t kid yourself: it’s also the flinch. Your personality is not set in stone. You may think a morning coffee is the most enjoyable thing in the world, but it’s really just a habit. Thirty days without it, and you would be fine. You think you have a soul mate, but in fact you could have had any number of spouses. You would have evolved differently, but been just as happy. You can change what you want about yourself at any time. You see yourself as someone who can’t write or play an instrument, who gives in to temptation or makes bad decisions, but that’s really not you. It’s not ingrained. It’s not your personality. Your personality is something else, something deeper than just preferences, and these details on the surface, you can change anytime you like. If it is useful to do so, you must abandon your identity and start again. Sometimes, it’s the only way.”

— Julien Smith, The Flinch (via wnq-anonymous)

The older u are the more compelling and s*xy and complex u and your life become so the glorification of youth will always remain ludicrous to me

“ On the calm black water where the stars are sleeping

White Ophelia floats like a great lily… ”

English is weird

John McWhorter, The Week, December 20, 2015

English speakers know that their language is odd. So do nonspeakers saddled with learning it. The oddity that we all perceive most readily is its spelling, which is indeed a nightmare. In countries where English isn’t spoken, there is no such thing as a spelling bee. For a normal language, spelling at least pretends a basic correspondence to the way people pronounce the words. But English is not normal.

Even in its spoken form, English is weird. It’s weird in ways that are easy to miss, especially since Anglophones in the United States and Britain are not exactly rabid to learn other languages. Our monolingual tendency leaves us like the proverbial fish not knowing that it is wet. Our language feels “normal” only until you get a sense of what normal really is.

There is no other language, for example, that is close enough to English that we can get about half of what people are saying without training and the rest with only modest effort. German and Dutch are like that, as are Spanish and Portuguese, or Thai and Lao. The closest an Anglophone can get is with the obscure Northern European language called Frisian. If you know that tsiis is cheese and Frysk is Frisian, then it isn’t hard to figure out what this means: Brea, bûter, en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk. But that sentence is a cooked one, and overall, we tend to find Frisian more like German, which it is.

We think it’s a nuisance that so many European languages assign gender to nouns for no reason, with French having female moons and male boats and such. But actually, it’s we who are odd: Almost all European languages belong to one family–Indo-European–and of all of them, English is the only one that doesn’t assign genders.

More weirdness? OK. There is exactly one language on Earth whose present tense requires a special ending only in the third-person singular. I’m writing in it. I talk, you talk, he/she talks–why? The present-tense verbs of a normal language have either no endings or a bunch of different ones (Spanish: hablo, hablas, habla). And try naming another language where you have to slip do into sentences to negate or question something. Do you find that difficult?

Why is our language so eccentric? Just what is this thing we’re speaking, and what happened to make it this way?

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it’s a stretch to think of them as the same language. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon–does that really mean “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained English-speaker’s eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that when the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought Germanic speech to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke Celtic languages–today represented by Welsh and Irish, and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders, very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their own Celtic was quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). Also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: They used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker–as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones.

At this date there is no documented language on Earth beyond Celtic and English that uses do in just this way. Thus English’s weirdness began with its transformation in the mouths of people more at home with vastly different tongues. We’re still talking like them, and in ways we’d never think of. When saying “eeny, meeny, miny, moe,” have you ever felt like you were kind of counting? Well, you are–in Celtic numbers, chewed up over time but recognizably descended from the ones rural Britishers used when counting animals and playing games. “Hickory, dickory, dock”–what in the world do those words mean? Well, here’s a clue: hovera, dovera, dick were eight, nine, and ten in that same Celtic counting list.

The second thing that happened was that yet more Germanic-speakers came across the sea meaning business. This wave began in the 9th century, and this time the invaders were speaking another Germanic offshoot, Old Norse. But they didn’t impose their language. Instead, they married local women and switched to English. However, they were adults and, as a rule, adults don’t pick up new languages easily, especially not in oral societies. There was no such thing as school, and no media. Learning a new language meant listening hard and trying your best.

As long as the invaders got their meaning across, that was fine. But you can do that with a highly approximate rendition of a language–the legibility of the Frisian sentence you just read proves as much. So the Scandinavians did more or less what we would expect: They spoke bad Old English. Their kids heard as much of that as they did real Old English. Life went on, and pretty soon their bad Old English was real English, and here we are today: The Norse made English easier.

I should make a qualification here. In linguistics circles it’s risky to call one language easier than another one. But some languages plainly jangle with more bells and whistles than others. If someone were told he had a year to get as good at either Russian or Hebrew as possible, and would lose a fingernail for every mistake he made during a three-minute test of his competence, only the masochist would choose Russian–unless he already happened to speak a language related to it. In that sense, English is “easier” than other Germanic languages, and it’s because of those Vikings.

Old English had the crazy genders we would expect of a good European language–but the Scandinavians didn’t bother with those, and so now we have none. What’s more, the Vikings mastered only that one shred of a once lovely conjugation system: Hence the lonely third-person singular -s, hanging on like a dead bug on a windshield. Here and in other ways, they smoothed out the hard stuff.

They also left their mark on English grammar. Blissfully, it is becoming rare to be taught that it is wrong to say Which town do you come from?–ending with the preposition instead of laboriously squeezing it before the wh-word to make From which town do you come? In English, sentences with “dangling prepositions” are perfectly natural and clear and harm no one. Yet there is a wet-fish issue with them, too: Normal languages don’t dangle prepositions in this way. Every now and then a language allows it: an indigenous one in Mexico, another in Liberia. But that’s it. Overall, it’s an oddity. Yet, wouldn’t you know, it’s a construction that Old Norse also happened to permit (and that modern Danish retains).

We can display all these bizarre Norse influences in a single sentence. Say That’s the man you walk in with, and it’s odd because (1) the has no specifically masculine form to match man, (2) there’s no ending on walk, and (3) you don’t say in with whom you walk. All that strangeness is because of what Scandinavian Vikings did to good old English back in the day.

Finally, as if all this weren’t enough, English got hit by a fire-hose spray of words from yet more languages. After the Norse came the French. The Normans–descended from the same Vikings, as it happens–conquered England and ruled for several centuries, and before long, English had picked up 10,000 new words. Then, starting in the 16th century, educated Anglophones began to develop English as a vehicle for sophisticated writing, and it became fashionable to cherry-pick words from Latin to lend the language a more elevated tone.

It was thanks to this influx from French and Latin (it’s often hard to tell which was the original source of a given word) that English acquired the likes of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion. These words feel sufficiently English to us today, but when they were new, many persons of letters in the 1500s (and beyond) considered them irritatingly pretentious and intrusive, as indeed they would have found the phrase “irritatingly pretentious and intrusive.” There were even writerly sorts who proposed native English replacements for those lofty Latinates, and it’s hard not to yearn for some of these: In place of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion, how about crossed, groundwrought, saywhat, and endsay?

But language tends not to do what we want it to. The die was cast: English had thousands of new words competing with native English words for the same things. One result was triplets allowing us to express ideas with varying degrees of formality. Help is English, aid is French, assist is Latin. Or, kingly is English, royal is French, regal is Latin–note how one imagines posture improving with each level: Kingly sounds almost mocking, regal is straight-backed like a throne, royal is somewhere in the middle, a worthy but fallible monarch.

Then there are doublets, less dramatic than triplets but fun nevertheless, such as the English/French pairs begin/commence and want/desire. Especially noteworthy here are the culinary transformations: We kill a cow or a pig (English) to yield beef or pork (French). Why? Well, generally in Norman England, English-speaking laborers did the slaughtering for moneyed French speakers at the table. The different ways of referring to meat depended on one’s place in the scheme of things, and those class distinctions have carried down to us in discreet form today.

The multiple influxes of foreign vocabulary partly explain the striking fact that English words can trace to so many different sources–often several within the same sentence. The very idea of etymology being a polyglot smorgasbord, each word a fascinating story of migration and exchange, seems everyday to us. But the roots of a great many languages are much duller. The typical word comes from, well, an earlier version of that same word and there it is. The study of etymology holds little interest for, say, Arabic speakers.

To be fair, mongrel vocabularies are hardly uncommon worldwide, but English’s hybridity is high on the scale compared with most European languages. The previous sentence, for example, is a riot of words from Old English, Old Norse, French, and Latin. Greek is another element: In an alternate universe, we would call photographs “lightwriting.”

Because of this fire-hose spray, we English speakers also have to contend with two different ways of accenting words. Clip on a suffix to the word wonder, and you get wonderful. But–clip an ending to the word modern and the ending pulls the accent along with it: MO-dern, but mo-DERN-ity, not MO-dern-ity. That doesn’t happen with WON-der and WON-der-ful, or CHEER-y and CHEER-i-ly. But it does happen with PER-sonal, person-AL-ity.

What’s the difference? It’s that -ful and -ly are Germanic endings, while -ity came in with French. French and Latin endings pull the accent closer–TEM-pest, tem-PEST-uous–while Germanic ones leave the accent alone. One never notices such a thing, but it’s one way this “simple” language is actually not so.

Thus English is indeed an odd language, and its spelling is only the beginning of it. What English does have on other tongues is that it is deeply peculiar in the structural sense. And it became peculiar because of the slings and arrows–as well as caprices–of outrageous history.

Again I quoted a poet - to avoid sounding like a preacher myself - who had written, ‘What you have experienced, no power on earth can take from you.’ Not only our experiences, but all we have done, whatever great thoughts we may have had, and all we have suffered, all this is not lost, though it is past; we have brought it into being. Having been is also a kind of being, and perhaps the surest kind.

Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

The Grotto of Venus built by Mad King Ludwig II, the perfect place to take a paramour.

Pistol compact with powder, rouge, and bullet-shaped lipstick, Circa 1920.

“The gaze, human or animal, is a powerful thing. When we look at something, we decide to fill our entire existence, however briefly, with that very thing. To fill your whole world with a person, if only for a few seconds, is a potent act. And it can be a dangerous one. Sometimes we are not seen enough, and other times we are seen too thoroughly, we can be exposed, seen through, even devoured. Hunters examine their prey obsessively in order to kill it. The line between desire and elimination, to me, can be so small. But that is who we are. There must be some beauty—and if not beauty, meaning—in that brutal power. I am still trying, and mostly failing, to find it.”

— Ocean Vuong, Survival as a Creative Force

the cruel prince, 2018

richard iii, 1593

frankenstein, 1818

I want to be famous, doing what? Everything! I will never be a poet, or a philosopher, or a scholar. I can only be a singer or painter. I want to be in vogue; that is the principal thing. Don’t shrug your shoulders, strict people, don’t criticize me with an affected indifference. You are just the same at the bottom. You are careful not to let it show. But that doesn’t keep you from finding, deep in yourselves, that I tell the truth. Vanity! Vanity! Vanity! The beginning and the end of everything, and the sole and eternal cause of everything. Whatever is not produced by vanity is born from our passions. Passions and vanity are the only masters of the world.

Marie Bashkirtseff, 5th April 1876 (via early20thcenturynerd)

there is no audience to perform for, there is no approval, no admiration to attain. there is no role worth playing, there is no one to convince. let it go

“[W]hat does the sentence “If you eat this fruit you will die” mean for Eve who is in a place where there is no death?”

— Hélène Cixous, Readings: The Poetics of Blanchot, Joyce, Kakfa, Kleist, Lispector, and Tsvetayeva.

Hung on my bedroom wall is the quote attributed to Joan of Arc: “I am not afraid. I was born to do this.” However my life unfolds, goes my thinking, is how I am meant to live it; however my life unspools itself, I was created to bear it.

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias (via fuckyeahannecarson)