Electra ‼️‼️

Electra ‼️‼️

ref : courage anxiety and despair: watching the battle (James Sant 1850)

More Posts from Phaespxria and Others

Πέμπτη Μεσοῦντος/ Πέμπτη ἐπὶ δέκα / Πεντεκαιδεκάτη, XV day From today’s sunset: fifteenth day of Maimakterion. The fifteenth of the month is always sacred to Athena. “Shun the fifth days: i.e. the lunar days. Shun all the fifth days.” (A woman- Cassandra?- embraces the statue of Athena; from Tanagra, 400 BC–323 BC, Besques-Mollard, Simone 1950 Tanagra. Braun & Co., Paris, France. (5-9)

glorious evolution

Al Pacino in Serpico

They're talking about horse riding

hector sketch (he's ready to go butcher people)

‘The Divine Eros Defeats the Earthly Eros’ (detail) by Giovanni Baglione, c. 1602.

There's been some amount of academic discussion about Paris' two names - usually in terms of which is earlier and where they come from and what epithets are used with which name. (Most of his epithets "belong" only to Alexander, if you're curious.) But, a small branch of it is "who uses what name, in-story, in the Iliad" ; Ann Suter (this woman, uhh her ideas are pretty crazy so approach with awareness of that), I.F. de Jong and, commenting on especially the latter's article, Michael Lloyd.

I lean more towards Lloyd's assessment that de Jong's premise (that "Paris" is between the Trojans and "Alexander" for the Achaeans as a sort of 'international' name) can't really be supported. But! That doesn't mean you still can't have fun with the split in names and get something in terms of character and worldbuilding out of that!

So, first of all, in the Iliad, "Alexander" is used far more than "Paris". Only Hektor ever uses "Paris" in direct speech, about or to him (we'll get back to Hektor).

Everyone else, Achaean or Trojan, uses Alexander.

Both Suter and de Jong would, in various ways, either ignore this or explain it away as a "this only happens when the Trojans are talking to Achaeans" (Hektor, before the duel), or "what is said is going to be said to Achaeans" (Priam, telling Idaeus what to report to the Achaean commanders). Honestly, that seems overly complicated and not very reasonable to me. Especially in the case of Priam, if Paris was the name he's most used to using, there is no reason for him not to use Paris and then Idaeus simply switches when reporting the speech to the Achaeans. Yes, reported speech/instructions are usually relayed verbatim, but switching a name wouldn't be changing what's actually been said.

And, anyway, coming back to Hektor, who is the one to most consistently use Paris? Also uses Alexander, when thinking to himself, in his own head. (He also uses Paris to Achilles.)

Myth-wise, in various later sources you get the very logical conclusion of "one name was given by his foster father, the other by his royal parents". (Though there's not necessarily any consistency, even with one writer, which name was given by whom.)

Given the way the Iliad prioritises Alexander, I'd go with that Alexander is the name Priam and Hecuba gave their son, even if he was going to be exposed, before giving him away. Given how Alexander is used by basically everyone to address him, this would make good sense, I think. The Achaeans would only know of Alexander, prince of Troy, and that is certainly the name most/all Trojans would use. Paris is then the name given him by his foster father. Hektor using it can be turned into a look into their relationship, because what you see is Hektor using the name of the "outsider" (by a bare technically "not" his brother), to insult his brother, when he's angry. A verbal distance to add to the emotional one, if not one that's complete and sometimes blurs.

(This doesn't take into account post-Iliad sources, where 'Paris' vastly outnumber the uses of 'Alexander'.)

thinking about heroes wishing to switch places........

[...] when Odysseus meets the shade of Achilles, he addresses Achilles as "best of the Achaeans". But the Odyssey then has Achilles saying that he would rather be alive and the lowliest of serfs than to be dead and the kingliest of shades. [...] Achilles seems ready to trade places with Odysseus, whose safe homecoming will be marked by a painful transitional phase at the very lowest levels of the social order. The words of Achilles in the first nekuia are ironically conjuring up the glorious days of the Iliad when he had said: "I have lost a safe return home [nostos], but I will have unfailing glory [kleos]." (IX 413) The destiny of the Odyssey is that Odysseus shall have a nostos, 'safe return home'. From the retrospective vantage point of the Odyssey, Achilles would trade his kleos for a nostos. It is as if he now would trade an Iliad for an Odyssey. By contrast, at a moment when Odysseus is sure that he will perish in the stormy sea, he wishes that he had died at Troy: "...and then the Achaeans would have carried on my kleos." (v 308-311)

From Gregory Nagy's The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the hero in ancient Greek poetry (1979)

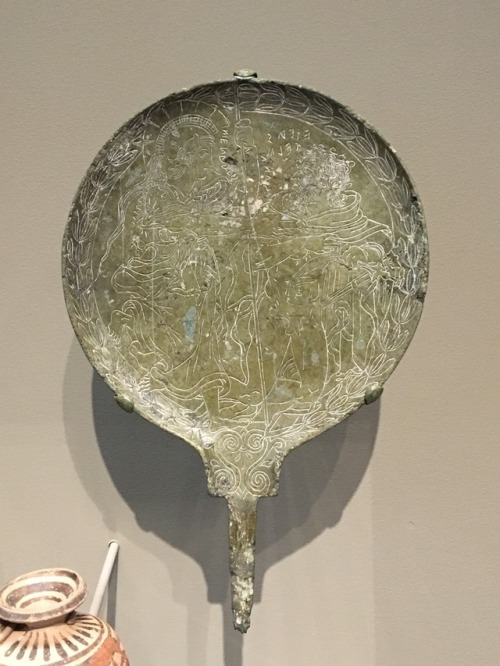

This Etruscan mirror of Athena and Ajax is amazing because it’s a uniquely Etruscan conception of the myth where Athena literally urges Ajax to commit suicide rather than simply driving him mad. Today I got to see it in person at the Boston Museum Of Fine Art!

-

idcaboutmynickname liked this · 1 week ago

idcaboutmynickname liked this · 1 week ago -

anonyjays liked this · 1 week ago

anonyjays liked this · 1 week ago -

sofmaart liked this · 1 week ago

sofmaart liked this · 1 week ago -

citrusbian liked this · 2 weeks ago

citrusbian liked this · 2 weeks ago -

telemaqus reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

telemaqus reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

telemaqus liked this · 2 weeks ago

telemaqus liked this · 2 weeks ago -

mariibarrasworld liked this · 3 weeks ago

mariibarrasworld liked this · 3 weeks ago -

noctivagant-corvid liked this · 3 weeks ago

noctivagant-corvid liked this · 3 weeks ago -

sepia-stained-sunset liked this · 3 weeks ago

sepia-stained-sunset liked this · 3 weeks ago -

viathewhimsy liked this · 3 weeks ago

viathewhimsy liked this · 3 weeks ago -

jp9639 liked this · 3 weeks ago

jp9639 liked this · 3 weeks ago -

dasfeministmermaid reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

dasfeministmermaid reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

secunit-3 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

secunit-3 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

wouldyouwannatakeapicture liked this · 3 weeks ago

wouldyouwannatakeapicture liked this · 3 weeks ago -

drunkwalkhme liked this · 3 weeks ago

drunkwalkhme liked this · 3 weeks ago -

lovemyths reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

lovemyths reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

laymedowninsheetsoflinen liked this · 1 month ago

laymedowninsheetsoflinen liked this · 1 month ago -

redrosesandcharmingsouls reblogged this · 1 month ago

redrosesandcharmingsouls reblogged this · 1 month ago -

redrosesandcharmingsouls liked this · 1 month ago

redrosesandcharmingsouls liked this · 1 month ago -

furiousglitternightmare liked this · 1 month ago

furiousglitternightmare liked this · 1 month ago -

simplysslytherin liked this · 1 month ago

simplysslytherin liked this · 1 month ago -

lemedstudent2021 liked this · 1 month ago

lemedstudent2021 liked this · 1 month ago -

ultear13 liked this · 1 month ago

ultear13 liked this · 1 month ago -

constantwords liked this · 1 month ago

constantwords liked this · 1 month ago -

thematicparallel liked this · 1 month ago

thematicparallel liked this · 1 month ago -

evenaturtleduck liked this · 1 month ago

evenaturtleduck liked this · 1 month ago -

river-gale reblogged this · 1 month ago

river-gale reblogged this · 1 month ago -

river-gale liked this · 1 month ago

river-gale liked this · 1 month ago -

blue-glasses-dork reblogged this · 1 month ago

blue-glasses-dork reblogged this · 1 month ago -

blue-glasses-dork liked this · 1 month ago

blue-glasses-dork liked this · 1 month ago -

dolihannah liked this · 1 month ago

dolihannah liked this · 1 month ago -

downqrumpy liked this · 1 month ago

downqrumpy liked this · 1 month ago -

coldbleed liked this · 1 month ago

coldbleed liked this · 1 month ago -

loires reblogged this · 1 month ago

loires reblogged this · 1 month ago -

shchiglov liked this · 1 month ago

shchiglov liked this · 1 month ago -

leviiiathen liked this · 1 month ago

leviiiathen liked this · 1 month ago -

abielaabitalescarraglimnt1 liked this · 1 month ago

abielaabitalescarraglimnt1 liked this · 1 month ago -

someabsolutenonsense liked this · 1 month ago

someabsolutenonsense liked this · 1 month ago -

shycreationmilkshake liked this · 1 month ago

shycreationmilkshake liked this · 1 month ago -

maviizzz liked this · 1 month ago

maviizzz liked this · 1 month ago -

secunit-3 liked this · 1 month ago

secunit-3 liked this · 1 month ago -

quite-the-mystery liked this · 1 month ago

quite-the-mystery liked this · 1 month ago -

galaxylychee liked this · 1 month ago

galaxylychee liked this · 1 month ago -

spookytorosaurus liked this · 1 month ago

spookytorosaurus liked this · 1 month ago -

practicalgothicism reblogged this · 1 month ago

practicalgothicism reblogged this · 1 month ago -

practicalgothicism liked this · 1 month ago

practicalgothicism liked this · 1 month ago -

shcheglik liked this · 1 month ago

shcheglik liked this · 1 month ago -

sunspawn22 liked this · 1 month ago

sunspawn22 liked this · 1 month ago