“How As A Girl, In Cut-off Jeans And A Skimpy String-bikini Top, I Lay In The Back Of A Pick-up Truck,

“How as a girl, in cut-off jeans and a skimpy string-bikini top, I lay in the back of a pick-up truck, the better to bronze my young, bare flesh. How I wanted to scorch myself, then; how I wanted to burn my beauty onto the very eye of love. How lovely, the way we wreck ourselves on the world; how we shine in it, too.”

— Cecilia Woloch, ‘Girl in a Truck, Kentucky Highway 245’, in Narcissus (via antigonies)

More Posts from Purposefullylackadaisical and Others

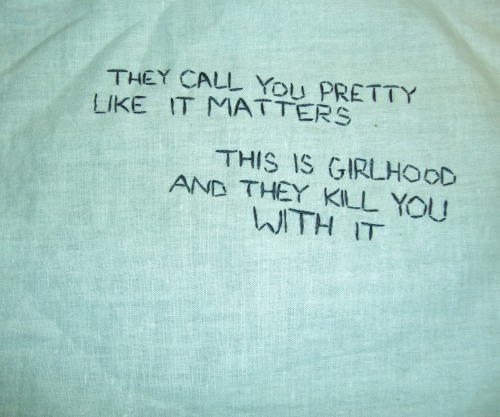

— mimi evangeline, from girlhood is godhood

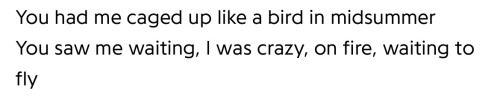

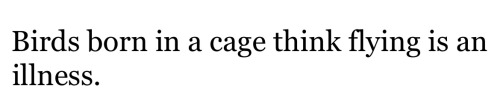

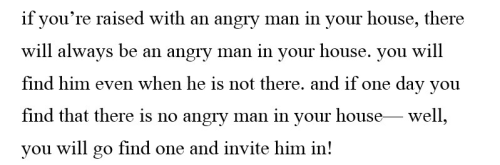

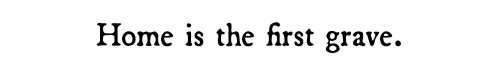

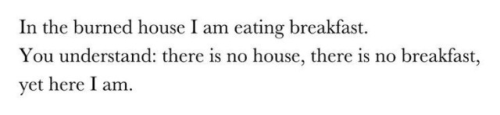

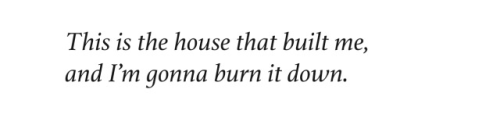

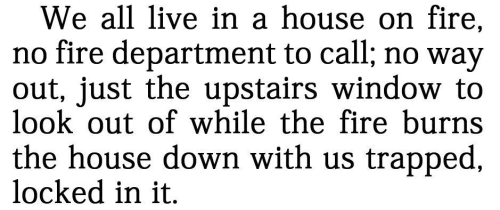

Aloha from Hell - Richard Kadrey / x / I Can Fly - Lana Del Rey / Alejandro Jodorowsky / Cut - Catherine Lacey / How’d Your Parents Die Again? - Fatimah Asghar / Margaret Atwood / Courtney Love Prays To Oregon - Clementine von Radics / The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore - Tennessee Williams / Vesuvius - Amber Sparks

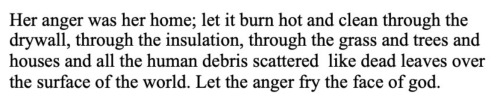

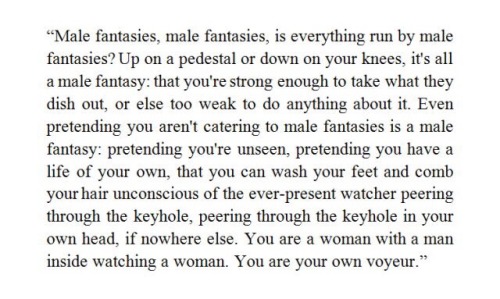

— Angela Carter, from The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography, c. 1978.

“I held my grief like two limp tulips. What am I allowed to have? I’m still here. I’m still hers. I’m still a body licked by stars.”

— “Departure” by Erika L. Sánchez (via decreation)

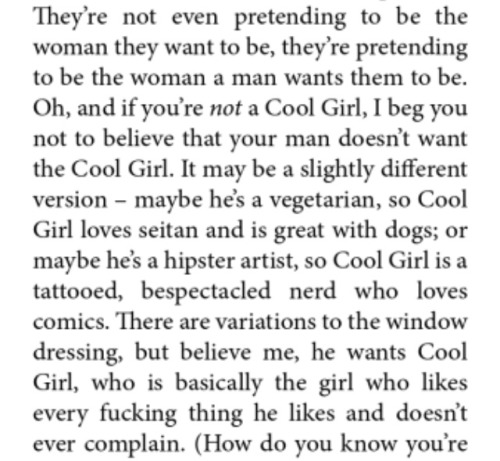

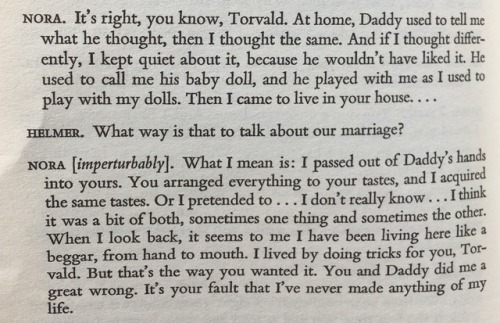

a short collection on catering to men. Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn (2012) A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen (1879) The Robber Bride by Margaret Atwood (1993)

Venomous Silence

Vincent Van Gogh// The Little Mermaid// The Jacaranda Years, Yiwei Chai// "A Garden", Lyric Hunter//

Trista Mateer, Honeybee

Olena Kalytiak Davis, Shattered Sonnets, Love Cards, and Other Off and Back Handed Importunities

Sharon Olds, True Love

Stephen Crane, In The Desert

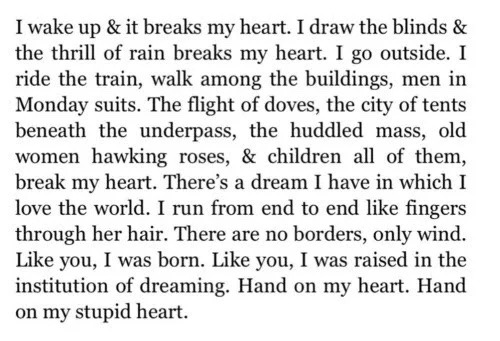

Cameron Awkward-Rich, Meditations in an Emergency

ANTIGONE: The fields were wet. They were waiting for something to happen. The whole world was breathless, waiting. I can’t tell you what a roaring noise I seemed to make alone on the road. It bothered me that whatever was waiting, wasn’t waiting for me.

Jean Anouilh, Antigone

Etel Adnan, The Spring Flowers Own & The Manifestations of the Voyage

I’m trying to give you everything I have. But I can’t find it; I can’t find it yet.

Alice Notley, In The Pines

Anne Carson, Plainwater: Essays and Poetry

& if I were to forgive you (& I know I could)

who would be left

who would be left

to forgive me?

Hieu Minh Nguyen, Afterwards

Mahmoud Darwish, Mural

Fariha Róisín, How to Cure a Ghost

“You kiss the back of my legs and I want to cry. Only / the sun has come this close, only the sun.”

Shauna Barbosa, GPS

Mahmoud Darwish, Mural

Forough Farrokhzad, Another Birth

repetition in poetry // part i

(part ii) (part iii) (part iv) (part v)

what do you think drives lady macbeth's cruelty and do you sympathise with her at all?

This post and this post might be of interest. But I think ‘cruelty’ is the wrong word. Cruelty implies violence for the sake of violence and enjoyment of violence. (See here.) Lady M doesn’t revel in the violence. She doesn’t delight in it the way some of the characters in, say, Titus Andronicus do, or even Margaret in Henry VI does after the murder of Rutland/during the murder of York. For Lady M violence is always a means to an end. “Infirm of purpose” is what she calls her husband when he starts to get faint-hearted. He’s too full of the milk of human kindness “to catch the nearest way.” For her, it’s all about the outcome. The ends justify the means. Like I said in one of those posts, I think her driving force is ambition. She wants more than what she has.

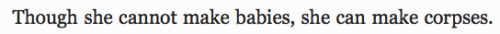

Interestingly, she never expresses any personal desire to be queen. She does, however, use the singular possessive pronoun ‘my’ when she says “The raven himself is hoarse / That croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan / Under my battlements.” She claims the crime as her own, and even though the idea of murder occurs to her and her husband independently, she is the criminal mastermind. She says, “you shall put / This night’s great business into my dispatch; / Which shall to all our nights and days to come / Give solely sovereign sway and masterdom.” And at the end of the scene: “Leave all the rest to me.” This regicide is her baby–and I use that word very deliberately. There are a million possible explanations for why Lady Macbeth is so desperate to seize this power for her husband. My guess is it has something to do with that baby she mentions in 1.7 which doesn’t appear in the play. A woman’s function at this point in history was basically to be a baby-making machine and ensure the survival of her husband’s line. She hasn’t been able to do that (for whatever reason) and her husband, at least, is already middle-aged, so that procreation window is rapidly closing, if it’s not closed already. By early modern standards, that’s a huge dynastic failure. My guess is that her power-grabbing is about agency and compensation. Maybe she can’t continue Macbeth’s line, but she can make him king. And she does.

But here’s the other part of it which I think is really important and often gets overlooked, and it goes back to the fact that Lady M never expresses a personal desire to be queen. She wants her husband to be king, and she thinks he is fully deserving of that office. “Thou wouldst be great;” she says, “Art not without ambition, but without / The illness should attend it.” AND THIS IS SO KEY. Because Lady M is nothing if not full of ambition. What she’s saying here is “You don’t have enough darkness in your soul to do this, so I’m going to do it for you.” Now. Is that somewhat fucked up? Absolutely. However, that is an enormous sacrifice to make. I’m not going to get into this in depth, but there’s a lot of natural law theory floating around in this play. What’s important to know is this: In the protestant ethos of this play, if you commit regicide, you are 100% going to be damned for eternity. There’s no doubt about that. So, in an insane backwards way, this is actually an incredibly loving, selfless thing to do on Lady M’s part. She is willing to sacrifice her own salvation to make her husband king. Let that sink in. That is so much more hardcore than just saying, “I’d take a bullet for you, babe.” She is willing to burn for all time to put him on the throne, and not only is she willing, but it’s her idea, not just something she does with her back against the wall. That is a crazy kind of love. And that’s one of my favorite things about this play. This is not a unanimous opinion by any means, but I firmly believe that even though the Macbeths are terrible tyrannical people, they are desperately, devotedly in love with one another. Their language is incredibly intimate. In his first letter Macbeth addresses his wife as “My dearest partner of greatness,” and throughout the play they are constantly struggling to help and heal one another. Theirs is a relationship built on love and equality, whatever else they do (and however their relationship is also sometimes toxic and fractures through the play). Look at Macbeth’s conversation with the doctor in 5.3 when his wife’s health begins to fail: “If thou couldst, doctor, cast / The water of my land, find her disease, / And purge it to a sound and pristine health, / I would applaud thee to the very echo, / That should applaud again.” That. Is. Love.

So. Why does Lady Macbeth do the terrible things she does? There’s no certain answer. Ambition has a lot to do with it. But I think that ambition is rooted in guilt about what she hasn’t been able to provide her husband with, and a passionate yearning to make up for that, somehow. Leo’s character says in Inception that positive emotion trumps negative emotion every time, and I think that’s true here. Lady M doesn’t orchestrate Duncan’s murder because she’s inherently cruel. She does it for love.

-

purposefullylackadaisical reblogged this · 1 year ago

purposefullylackadaisical reblogged this · 1 year ago -

breathemeinlikeavapor reblogged this · 2 years ago

breathemeinlikeavapor reblogged this · 2 years ago -

un-a-bash-ed-ly reblogged this · 4 years ago

un-a-bash-ed-ly reblogged this · 4 years ago -

shanleenkinnjaskey reblogged this · 4 years ago

shanleenkinnjaskey reblogged this · 4 years ago -

shanleenkinnjaskey liked this · 4 years ago

shanleenkinnjaskey liked this · 4 years ago -

saturnocturnal liked this · 4 years ago

saturnocturnal liked this · 4 years ago -

x-fucked-up-society liked this · 5 years ago

x-fucked-up-society liked this · 5 years ago -

psyrinn liked this · 5 years ago

psyrinn liked this · 5 years ago -

lloronadivina liked this · 5 years ago

lloronadivina liked this · 5 years ago -

godsopenwound reblogged this · 5 years ago

godsopenwound reblogged this · 5 years ago -

godsopenwound liked this · 5 years ago

godsopenwound liked this · 5 years ago -

hellothewastedgeneration reblogged this · 5 years ago

hellothewastedgeneration reblogged this · 5 years ago -

tadokorocchi liked this · 5 years ago

tadokorocchi liked this · 5 years ago -

allhearthardlyanyhead reblogged this · 5 years ago

allhearthardlyanyhead reblogged this · 5 years ago -

graced-lightning reblogged this · 5 years ago

graced-lightning reblogged this · 5 years ago -

nephyria liked this · 6 years ago

nephyria liked this · 6 years ago -

bisvxuality liked this · 6 years ago

bisvxuality liked this · 6 years ago -

epicdogymoment liked this · 6 years ago

epicdogymoment liked this · 6 years ago -

onahotrock liked this · 6 years ago

onahotrock liked this · 6 years ago -

armillariarot reblogged this · 6 years ago

armillariarot reblogged this · 6 years ago -

sserendlplty reblogged this · 6 years ago

sserendlplty reblogged this · 6 years ago -

hellsonnig liked this · 6 years ago

hellsonnig liked this · 6 years ago -

brazenlunaaa liked this · 6 years ago

brazenlunaaa liked this · 6 years ago -

imossyou reblogged this · 6 years ago

imossyou reblogged this · 6 years ago -

thedreadfulwhale reblogged this · 6 years ago

thedreadfulwhale reblogged this · 6 years ago -

khushboo7mathuria liked this · 6 years ago

khushboo7mathuria liked this · 6 years ago -

scoutemmanuel reblogged this · 6 years ago

scoutemmanuel reblogged this · 6 years ago -

ar-ch-ie liked this · 6 years ago

ar-ch-ie liked this · 6 years ago -

veladora liked this · 6 years ago

veladora liked this · 6 years ago -

secifosseluce reblogged this · 6 years ago

secifosseluce reblogged this · 6 years ago -

therooness liked this · 6 years ago

therooness liked this · 6 years ago -

periwinkle-life liked this · 6 years ago

periwinkle-life liked this · 6 years ago -

lovesyrup reblogged this · 6 years ago

lovesyrup reblogged this · 6 years ago -

falesteenya liked this · 6 years ago

falesteenya liked this · 6 years ago -

dahliaezzeddine liked this · 6 years ago

dahliaezzeddine liked this · 6 years ago -

thawrah reblogged this · 6 years ago

thawrah reblogged this · 6 years ago -

elsaclare liked this · 6 years ago

elsaclare liked this · 6 years ago -

lib-lub-jub liked this · 6 years ago

lib-lub-jub liked this · 6 years ago -

femmefantome liked this · 6 years ago

femmefantome liked this · 6 years ago -

milleanium liked this · 6 years ago

milleanium liked this · 6 years ago

95 posts