PRIDE MONTH

PRIDE MONTH

LOVE WHOEVER YOU WANT, BE WHOEVER YOU WANT

BE YOURSELF, LOVE YOURSELF.

More Posts from Snowwritings and Others

Me: *goes through my old posts and hcs*

Me: why was I so,,,,, embarrassing ?? Why did so many read that stuff ?? Do I really write like that ????? Did I really say that ???

![[flexes Muscles] Done With The Lines](https://64.media.tumblr.com/ae0feb7c65dd4be9d92c18a2d14b3377/tumblr_nz6ao5mqEI1ql5vkuo1_500.jpg)

[flexes muscles] done with the lines

Little tribute to the rover that’s had me emotional all day… RIP Oppy.

happy pride to everyone who’s still closeted

happy pride to everyone who’s been kicked out

happy pride to everyone who lives somewhere where it is illegal to love who they love

happy fucking pride to all of you, i love you with my whole heart and i promise you it will get better

Ways To Fit Character Development Into Your Story

– Here are some ways you can develop your characters (in little ways as well as big ones) without info dumping on your reader. This includes detailing their backstory, revealing their values and motivations, their strengths, weaknesses, relationships with other characters, and growth throughout your story. I hope this helps those of you who have expressed having trouble with this, as I have as well and creating this guide for myself and you will be very useful for all of us, I hope. Happy writing!

Backstory

First of all, only include events from a character’s past that has shaped them and will enlighten the reader on the current situation. Once you decide that this particular event is important enough to include, show it instead of tell it. Elude to backstory instead of literally plucking it out of the past and placing it in the reader’s lap.

Instead of telling the reader that your character was in an abusive relationship, show them the aftermath where your character now has their abuser’s rules engraved into their routines and the scars, physical and metaphorical, that the character has from that experience. Yes, there will be instances where you will have to come out and say it, but do it once and lightly, then let the subtext do the rest.

Core Values & Motivation

Character development is meant to be shown, not told, and therefore, your character’s values, beliefs, and motivations should reveal themselves though the character’s actions. If your character thinks that harming any living creature is the worst crime anyone can commit, then show their struggle when they’re put in a situation where they must ignore their own conscience. These moments are not only pivotal in the reader’s experience with your character, but humanize your character more than any other story element. It is the moments in which we must fight our own nature that show what our nature truly is, and it’s the same with the fictional characters you’re writing about.

Strengths & Weaknesses

In a story, the conflict will do a lot to show where your character thrives and struggles, but you cannot rely solely on the main conflict. Maybe your character is incredibly smart, but not physically strong, and is put in a situation where they must rely on an area they’re weak in and must struggle in front of the reader. It’s the same with strengths. Your character should have moments of glorious triumph phenomenal failure throughout your story. This makes them more alive, and therefore more relatable, which is important in any story.

Relationships With Other Characters

Relationships with characters should be shown through the manner in which they communicate and interact in your story. If they don’t like each other, there will most likely be some tension when they’re forced to work together and rely on one another. If they love each other, they’ll show it through affectionate gestures and sometimes their words.

Growth & Personal Development

The beginning and ending of your story doesn’t have to be a miraculous before and after, but your character should go through some sort of a personal evolution between the start and finish line. Whether that be in their self-concept, their relationship with someone else, or their views on something, they should transform, at least a little. This is just a characteristic of a rounded character, and that’s what you want.

Show their development in ways such as putting them in a similar situation they’ve been in before and have them react in a way that highlights the change that has occurred. Show them realizing themselves that they have changed and now see through a different lens. Show them interacting differently as time progresses and imparting new words of wisdom, whether they’re correct or completely misguided.

Support Wordsnstuff!

If you enjoy my blog and wish for it to continue being updated frequently and for me to continue putting my energy toward answering your questions, please consider Buying Me A Coffee.

Request Resources, Tips, Playlists, or Prompt Lists

Instagram // Twitter //Facebook //#wordsnstuff

FAQ //monthly writing challenges // Masterlist

Every writer on Tumblr: “I would combust out of love if someone ever drew fanart of my fic!!” Me: “oh man I wanna draw this scene BUT THEY WOULD PROBABLY HATE IT AND HATE ME FOR THE NERVE”

You do what you hate to survive during a blight. No judgements here.

What if the fade being ripped open in da:i has nothing to do with templars and mages but everything to do with those weird side quests in da:o like activating the places of power and watch guard of the reaching and summoning sciences

I mean the warden did a bunch of weird shit in da:o without fully understanding what any of it does

I think you nailed it on the head. It certainly had issues, like the stuff with your religion choice and the lazy re-use of MC faces and the now regular forced male LI, but I agree everyone was certainly ready to jump on that bandwagon for multiple reasons.

Unpopular opinion: despite it's more serious issues, I actually enjoyed home for the holidays. I just took it for what it was worth. Plus I really liked Holly. She is gorgeous and I did not find her boring at all.

I’m neutral on this one, I’m not sure if it was actually a terrible book or we all just collectively agreed and followed along with what the majority said because if you disagree with everyone, well…

I only wish they used better MC’s faces instead of recycled love hacks ones

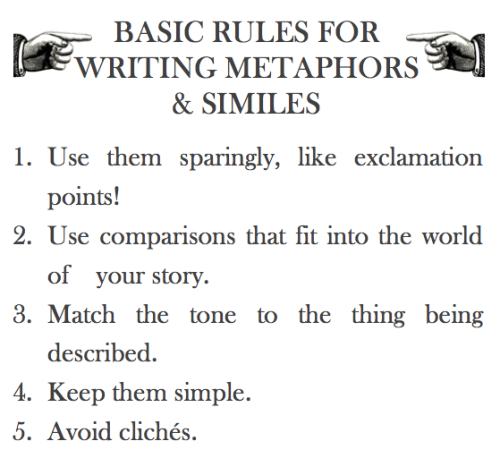

RULE #1: Use them sparingly.

Comparisons draw attention to themselves, like a single red tulip in a sea of yellow ones. They take the reader out of the scene for a moment, while you describe something that isn’t in it, like you’re pushing them out of the story. They require more thought than normal descriptions, as they ask the reader to think about the comparison, like an essay question in the middle of a multiple choice test. They make the image stand out, give it importance, a badge of honor of sorts.

Use too many comparisons and they become tedious.

Elevating every single description is like ending each sentence with an exclamation point. Eventually, the reader decides no one could possibly shout this much, and starts ignoring them.

For these reasons, you should only use metaphorical language when you really want to make an image stand out. Save them for important moments.

RULE #2: Use comparisons that fit into the world of your story.

If you’re writing from the point of view of a character who’s only ever lived in a desert, having that character say, “her look was as cold as snow” doesn’t make much sense. That character isn’t likely to have experienced snow, so it wouldn’t be a reference point to them. They’d be more likely to compare the look to a “moonless desert night” or something along those lines.

Using a comparison that ties to the character’s history or the setting of the story also do work to build the world of the story. It gives you a chance to show the reader exactly what your character’s reference points are, and builds the story’s world. If your reader doesn’t know that desert nights can get cold, this comparison informs both the things its describing: the other character’s look and the desert at night.

Here’s a metaphor from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

If you took a couple of David Bowies and stuck one of the David Bowies on the top of the other David Bowie, then attached another David Bowie to the end of each of the arms of the upper of the first two David Bowies and wrapped the whole business up in a dirty beach robe you would then have something which didn’t exactly look like John Watson, but which those who knew him would find hauntingly familiar.

He was tall and he was gangled.

This is a bizarre comparison, but it’s also a bizarre story. What’s more, David Bowie is known for his persona “Ziggy Stardust” and songs like “Space Oddity.” Bringing him up in a book about a man from Earth traversing the galaxy makes sense. What’s more it increases both of those aspects of the story: its ties to space and its bizarre-ness. The comparison unifies the story and the language being used to tell the story.

Using comparisons that fit into the world ensures that everything is working to help tell the story you want to tell.

RULE #3: Match the tone to the thing being described.

Or, match it to the way you want the thing being described to come across. It has to match what you want the reader to feel about the thing being described.

Here’s an example from Mental Floss’s “18 Metaphors & Analogies Found in Actual Student Papers” (although I think it’s actually from a bad metaphor writing contest):

She had a deep, throaty, genuine laugh, like that sound a dog makes just before it throws up.

You’re not imagining a laugh right now, are you? You’re imagining a dog throwing up. Whoever this girl is, you’re going to make sure never to tell a joke in front of her.

This is not getting the right point across.

Remember the David Bowies? Remember how the comparison was fun and bizarre, just like the tone of the book is fun and bizarre?

This is not David Bowies stacked on top of one another.

It’s not enough for a comparison to be accurate. It has to bring about the same emotions as the thing it’s describing.

If this is being told from the point of view of a character who hates the laughing character and we’re supposed to hate her and her laugh. It actually does work, but from the use of the word “genuine,” I don’t think this is the case.

Make sure you always pay attention to the tone of the comparison.

RULE #4: Keep them simple.

Don’t use a comparison that requires too much thought on the reader’s part. You never want anyone sparing even a moment on the question: “but how is x like y?”

Here’s another example from that Mental Floss list:

Long separated by cruel fate, the star-crossed lovers raced across the grassy field toward each other like two freight trains, one having left Cleveland at 6:36 p.m. traveling at 55 mph, the other from Topeka at 4:19 p.m. at a speed of 35 mph.

Again, this is a humorous example. It’s supposed to be bad, but many writers have made mistakes like it. They choose two images that don’t have enough in common for the reader to make an easy and obvious comparison between the two. Sometimes, the writer subconsciously acknowledges this, and expands the comparison to a paragraph, detailing the ways the two things are alike.

If you find yourself doing this, take a step back and ask yourself if this is really the best comparison to be using. The best comparisons are the simple ones. All the world’s a stage. Conscience is a man’s compass. Books are the mirrors of the soul.

What about that David Bowie quote, you ask? Douglas Adams broke this rule, but he broke it purposefully to get that bizarre quality to the language. He still avoids reader confusion, the reason for this rule, by bringing the comparison back to its point at the end: “he was tall and he was gangled.”

RULE #5: Avoid cliches.

The best comparisons are fresh ones. No one wants to hear that she had “skin as white as snow” and lips “as red as roses” anymore. The slight understanding it brings to the description isn’t worth the reader’s groans when they realize you just made them read that again.

A cliche is a waste of space on the page. It’s not going to be the memorable line you want it to be. It’s not going to awe the reader.

Good similes in metaphors require some creative thinking.

In the vein of rosy lips and snow-colored skin, here’s a fun example from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. It’s the poem that Ginny wrote for Harry on Valentine’s Day:

His eyes are as green as a fresh pickled toad,

His hair is as dark as a blackboard.

I wish he was mine, he’s really divine,

The hero who conquered the Dark Lord.

These aren’t comparisons you’re like to have come across before and their originality comes from rules #2 and #3. Rowling needed comparisons that fit in Ginny’s frame of reference. She also needed comparisons that were humorously bad, as they’re being recited by a grumpy creature dressed in a diaper, who is sitting on Harry’s ankles, forcing him to listen.

As a witch at school, blackboards and fresh pickled toads fit Ginny’s frame of reference. Neither are particularly known for being nice to look at, so they fit the tone, too.

Using her character, setting, and tone, using, in other words, her story, Rowling was able to create similes that are unique and memorable.

It’s the same thing Adams did with his Bowie analogy.

If you, too, use your story to inform your language, writing new and wonderful similes and metaphors should be just as simple.

This just warms my heart. How could this not be canon?

The idea of Cassandra and Dorian being trashy romance novel buddies delights me to no end.

(Especially if they’re the sort of people who can keep a blank face while reading smut but completely lose it over fluff)

-

prettyaffuq liked this · 4 months ago

prettyaffuq liked this · 4 months ago -

reinventboy reblogged this · 1 year ago

reinventboy reblogged this · 1 year ago -

dwelarobwhip liked this · 1 year ago

dwelarobwhip liked this · 1 year ago -

velcromouth reblogged this · 2 years ago

velcromouth reblogged this · 2 years ago -

crashingthruwindow reblogged this · 3 years ago

crashingthruwindow reblogged this · 3 years ago -

crashingthruwindow liked this · 3 years ago

crashingthruwindow liked this · 3 years ago -

oakandcirrus liked this · 3 years ago

oakandcirrus liked this · 3 years ago -

reinventboy reblogged this · 3 years ago

reinventboy reblogged this · 3 years ago -

itsthat0nefangirl liked this · 3 years ago

itsthat0nefangirl liked this · 3 years ago -

elemental-of-magic liked this · 3 years ago

elemental-of-magic liked this · 3 years ago -

prettypinkpastelparadise liked this · 3 years ago

prettypinkpastelparadise liked this · 3 years ago -

brendanporath liked this · 3 years ago

brendanporath liked this · 3 years ago -

li-centious liked this · 4 years ago

li-centious liked this · 4 years ago -

tylerisoffline reblogged this · 4 years ago

tylerisoffline reblogged this · 4 years ago -

reinventboy reblogged this · 4 years ago

reinventboy reblogged this · 4 years ago -

youngpadawan94 reblogged this · 4 years ago

youngpadawan94 reblogged this · 4 years ago -

spacepaprika liked this · 4 years ago

spacepaprika liked this · 4 years ago -

lore-dude liked this · 4 years ago

lore-dude liked this · 4 years ago -

quoisexual-asshole liked this · 4 years ago

quoisexual-asshole liked this · 4 years ago -

alliedisastermaster liked this · 4 years ago

alliedisastermaster liked this · 4 years ago -

mcristhebest17 liked this · 4 years ago

mcristhebest17 liked this · 4 years ago -

goodnightwindy liked this · 4 years ago

goodnightwindy liked this · 4 years ago -

crazyalien87 liked this · 4 years ago

crazyalien87 liked this · 4 years ago -

48tetra84 liked this · 4 years ago

48tetra84 liked this · 4 years ago -

icyryn liked this · 4 years ago

icyryn liked this · 4 years ago -

mermaidpowers1 liked this · 4 years ago

mermaidpowers1 liked this · 4 years ago -

lukechanelboots liked this · 4 years ago

lukechanelboots liked this · 4 years ago -

miss-nejire liked this · 4 years ago

miss-nejire liked this · 4 years ago -

mrslouispugh liked this · 4 years ago

mrslouispugh liked this · 4 years ago

Sofia. She/her. Writer, thinker, listener, trans woman, and supporter of the Oxford Comma.

172 posts