“From The River To The Sea.” A Poem By Samer Abu Hawwash, Translated By Huda Fakhreddine

“From the River to the Sea.” A Poem by Samer Abu Hawwash, translated by Huda Fakhreddine

every street, every house, every room, every window, every balcony, every wall, every stone, every sorrow, every word, every letter, every whisper, every touch, every glance, every kiss, every tree, every spear of grass, every tear, every scream, every air, every hope, every supplication, every secret, every well, every prayer, every song, every ballad, every book, every paper, every color, every ray, every cloud, every rain, every drop of rain, every drip of sweat, every lisp, every stutter, every yamma, mother, every yaba, father, every shadow, every light, every little hand that drew in a little notebook a tree or house or heart or a family of a father, a mother, siblings, and pets, every longing, every possibility, every letter between two lovers that arrived or didn’t arrive, every gasp of love dispersed in the distant clouds, every moment of despair at every turn, every suitcase on top of

every closet, every library, every shelf, every minaret, every rug, every bell toll in every church, every rosary, every holy praise, every arrival, every goodbye, every Good Morning, every Thank God, every ‘ala rasi, my pleasure, every hill ‘an sama’i, leave me alone, every rock, every wave, every grain of sand, every hair-do, every mirror, every glance in every mirror, every cat, every meow, every happy donkey, every sad donkey’s gaze, every pot, every vapor rising from every pot, every scent, every bowl, every school queue, every school shoes, every ring of the bell, every blackboard, every piece of chalk, every school costume, every mabruk ma ijakum, congratulations on the baby, every y ‘awid bi-salamtak, condolences, every ‘ayn al- ḥasud tibla bil-‘ama, may the envious be blinded, every photograph, every person in every photograph, every niyyalak, how lucky, every ishta’nalak, we’ve missed you, every grain of wheat in every bird’s gullet, every lock of hair, every hair knot, every hand, every foot, every football, every finger, every nail, every bicycle, every rider on every bicycle, every turn of air fanning from every bicycle, every bad joke, every mean joke, every laugh, every smile, every curse, every yearning, every fight, every sitti, grandma, every

sidi, grandpa, every meadow, every flower, every tree, every grove, every olive, every orange, every plastic rose covered with dust on an abandoned counter, every portrait of a martyr hanging on a wall since forever, every gravestone, every sura, every verse, every hymn, every ḥajj mabrur wa sa ‘yy mashkur, may your ḥajj and effort be rewarded, every yalla tnam yalla tnam, every lullaby, every red teddy bear on every Valentine’s, every clothesline, every hot skirt, every joyful dress, every torn trousers, every days-spun sweater, every button, every nail, every song, every ballad, every mirror, every peg, every bench, every shelf, every dream, every illusion, every hope, every disappointment, every hand holding another hand, every hand alone, every scattered thought, every beautiful thought, every terrifying thought, every whisper, every touch, every street, every house, every room, every balcony, every eye, every tear, every word, every letter, every name, every voice, every name, every house, every name, every face, every name, every cloud, every name, every rose, every name, every spear of grass, every name, every wave, every grain of sand, every street, every kiss, every image, every eye, every tear, every yamma, every yaba, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, all…

More Posts from Surmayah and Others

duuude you have GOT to get online everybody is just fucking hitting each other

“the arts and sciences are completely separate fields that should be pitted against each other” the overlap of the arts and sciences make up our entire perceivable reality they r fucking on the couch

liking people who live in the same city as you is so weird like i passed the flyover that connects our homes you made fun of me for not knowing it and now i do and you probably live here somewhere and i want to click a picture and send it to you and be like look!!! it's the colorful cable bridge near your house!!!! but i can't. because we don't fucking talk anymore 😭

i made an alt where i ramble even more thank you very much

unfortunately, to my parents’ disapproval, the one thing i truly dream of is having a home. i know i am supposed to dream big and “shatter the glass ceiling," and i do, but really, this is as close to my heart. i don't imagine the number of rooms and how big or small the house is, but i do dream about the sunlight coming through the windows, the quiet summer afternoons in the courtyard, the plants and flowers that are to be grown, along with the groceries to be bought. i dream of a gentle life with my beloved, where there will be no slamming of doors and neither of us will go to sleep with quiet resentment in our hearts that grows every day. i'll be able to hear the laughter of the children playing down the street, reverberating off the walls, and tell them stories—from the undying devotion between two lovers to the ventures of the fellow knight—while drinking tea on which too much money was spent for sugar, which leaves ring marks on the kitchen table. i dream of the books that are to be read, which will adorn every shelf and corner, and the paintings that are to be hung.

My loved ones are always welcome, irrespective of whether they want company, help, or words of kindness during trying times. i dream of the mehfils that are to be held, the ghazals that will be sung, and the shayeris that are to be recited. there will be winter nights spent huddled around the fire with my friends, where the courtyard will witness us dreaming aloud and revisiting old jokes. there'll be new recipes i'll learn, cupcakes i will bake, a favorite song i'll hum, and movies i'll watch. after all, some dreams are not about leaving legacies or achieving success in boardrooms; they do not call for applause, shine under spotlights, or get remembered in the pages of history. some of mine are more fragile, steadier—ones that have the comfort of a voice that calls for dinner, the creak of familiar wooden floors, the smell of fresh bread and candles of jasmine, with the last note of the serenade lingering in the air.

The assertion that the Mughals were colonizers is a misapplication of the term, one that conflates conquest with colonialism. Colonialism, as defined, involves the systematic exploitation of a territory for the benefit of a distant metropole, often accompanied by the imposition of foreign cultural and political structures while maintaining a clear separation between the colonizer and the colonized. The Mughals, however, do not fit this mold. They were not extractive outsiders but rather rulers who embedded themselves into the fabric of India, becoming part of its history rather than remaining external exploiters.

Let’s begin with intent. The Mughals did not arrive in India with the goal of extracting wealth to enrich a distant homeland. Unlike the British, who treated India as a resource colony to fuel their industrial revolution, the Mughals made India their home. Babur, the founder of the dynasty, may have been a conqueror, but his descendants—Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and even Aurangzeb—saw themselves as Indian rulers. They built their capital cities in India, patronized Indian arts, and integrated themselves into the subcontinent’s political and cultural landscape. This is not colonialism; it is empire-building, a process that has been a recurring theme in Indian history long before the Mughals arrived.

On the matter of cultural imposition, the Mughals were far more syncretic than colonial. Akbar’s policies, in particular, stand out as evidence of this. He abolished the jizya tax on non-Muslims, married Rajput princesses, and incorporated Hindu traditions into his court. His Din-i Ilahi, though short-lived, was an attempt to create a unifying spiritual framework that drew from multiple faiths. While the Mughals did impose Persian as the court language, they did not seek to erase Indian languages or traditions. Persian became a lingua franca, much like English did later, but it coexisted with regional languages and cultures. This is a far cry from the British, who sought to replace Indian systems with their own, often dismissing local traditions as backward.

Economically, the Mughals cannot be equated with colonizers. While it is true that wealth was concentrated in the hands of the elite—a feature common to most pre-modern empires—the Mughals reinvested their wealth in India. They built monumental architecture, funded arts and literature, and developed infrastructure. The British, by contrast, extracted wealth on an unprecedented scale, draining India’s resources to fuel their own industrial growth. The decline of India’s share of global GDP from 25% under the Mughals to 3.4% under the British is a stark reminder of this difference. The Mughals may not have created an egalitarian society, but they did not impoverish India for the benefit of a foreign power.

As for governance, the Mughals were far more inclusive than colonial powers. Akbar’s court, while dominated by Turani and Irani nobles, included Indian Hindus and Muslims. This was a significant departure from the British, who excluded Indians from positions of real power until the very end of their rule. The Mughals’ administrative system, the mansabdari, was open to Indians, and many Rajputs and Marathas rose to prominence within it. The British, on the other hand, maintained a rigid racial hierarchy, treating Indians as subjects rather than partners.

Finally, let’s address the cultural legacy. The Mughals are remembered not as foreign occupiers but as integral to India’s history. Their architecture, from the Taj Mahal to the Red Fort, is celebrated as part of India’s heritage. Their contributions to art, literature, and cuisine are woven into the fabric of Indian culture. The British, by contrast, left behind a legacy of division and exploitation. Their railways and administrative systems, while significant, were designed to serve their own interests, not India’s.

In conclusion, to label the Mughals as colonizers is to misunderstand both their role in Indian history and the nature of colonialism itself. They were conquerors, yes, but they were also builders, patrons, and, ultimately, participants in India’s story. The British, by contrast, were extractive outsiders who never saw India as anything more than a colony. The Mughals may not have been perfect rulers, but they were not colonizers. To conflate the two is to oversimplify a complex history—one that deserves to be understood on its own terms.

Not another post whining about why “mUgHaLs WeRe nOt cOlOnizErs” like girl, they were literally foreign invaders who forced you to speak their language, broke your temples, tried eradicating your culture and collected zizya taxes motivated by religious bigotry in hopes of forcing your people to convert! At least have some shame and consideration for your ancestors.

the ocean, my beloved 💌

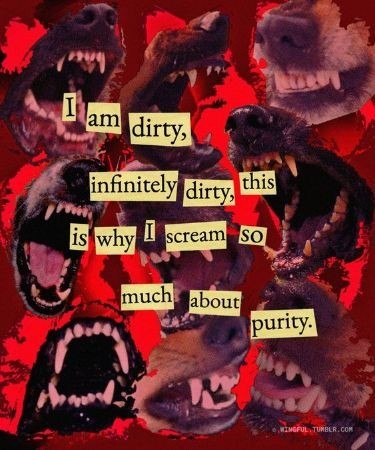

Oh, to be pure again

-

bulgarka liked this · 1 week ago

bulgarka liked this · 1 week ago -

softofheart reblogged this · 1 week ago

softofheart reblogged this · 1 week ago -

while-the-night-falls liked this · 1 month ago

while-the-night-falls liked this · 1 month ago -

illunerisms reblogged this · 1 month ago

illunerisms reblogged this · 1 month ago -

illunerism liked this · 1 month ago

illunerism liked this · 1 month ago -

nobodyimportant14 liked this · 1 month ago

nobodyimportant14 liked this · 1 month ago -

wordlessmelodies reblogged this · 1 month ago

wordlessmelodies reblogged this · 1 month ago -

4444a reblogged this · 1 month ago

4444a reblogged this · 1 month ago -

mallymun reblogged this · 2 months ago

mallymun reblogged this · 2 months ago -

fragileizy reblogged this · 2 months ago

fragileizy reblogged this · 2 months ago -

unstoppableflame liked this · 3 months ago

unstoppableflame liked this · 3 months ago -

daenerysion reblogged this · 3 months ago

daenerysion reblogged this · 3 months ago -

tesadoraofphaedra reblogged this · 3 months ago

tesadoraofphaedra reblogged this · 3 months ago -

riverfigs reblogged this · 4 months ago

riverfigs reblogged this · 4 months ago -

lucilfr liked this · 4 months ago

lucilfr liked this · 4 months ago -

she-is-a-city-cryptid liked this · 4 months ago

she-is-a-city-cryptid liked this · 4 months ago -

heartkreuz liked this · 4 months ago

heartkreuz liked this · 4 months ago -

movedto-luckystrikes liked this · 5 months ago

movedto-luckystrikes liked this · 5 months ago -

mudlark101 liked this · 5 months ago

mudlark101 liked this · 5 months ago -

serenrdipity reblogged this · 5 months ago

serenrdipity reblogged this · 5 months ago -

femmejardin reblogged this · 5 months ago

femmejardin reblogged this · 5 months ago -

dykescooby reblogged this · 5 months ago

dykescooby reblogged this · 5 months ago -

bowlingpinlane reblogged this · 5 months ago

bowlingpinlane reblogged this · 5 months ago -

bowlingpinlane liked this · 5 months ago

bowlingpinlane liked this · 5 months ago -

cdamnverss reblogged this · 5 months ago

cdamnverss reblogged this · 5 months ago -

dig1talbath reblogged this · 6 months ago

dig1talbath reblogged this · 6 months ago -

dig1talbath liked this · 6 months ago

dig1talbath liked this · 6 months ago -

cloudsaremadeofdreams reblogged this · 6 months ago

cloudsaremadeofdreams reblogged this · 6 months ago -

horseokmin reblogged this · 6 months ago

horseokmin reblogged this · 6 months ago -

prideandarrogance reblogged this · 6 months ago

prideandarrogance reblogged this · 6 months ago -

nenscript reblogged this · 6 months ago

nenscript reblogged this · 6 months ago -

rabbitdreamz liked this · 6 months ago

rabbitdreamz liked this · 6 months ago -

sagittariusangel reblogged this · 6 months ago

sagittariusangel reblogged this · 6 months ago -

onedayiamgoingtogrowwings liked this · 6 months ago

onedayiamgoingtogrowwings liked this · 6 months ago -

peepeepoopoobongboy reblogged this · 6 months ago

peepeepoopoobongboy reblogged this · 6 months ago -

hologram-evil liked this · 7 months ago

hologram-evil liked this · 7 months ago -

surmayah liked this · 7 months ago

surmayah liked this · 7 months ago -

maya-matlin reblogged this · 7 months ago

maya-matlin reblogged this · 7 months ago -

maya-matlin liked this · 7 months ago

maya-matlin liked this · 7 months ago -

thealternatemind reblogged this · 7 months ago

thealternatemind reblogged this · 7 months ago -

elegantpeanutinfluencer reblogged this · 7 months ago

elegantpeanutinfluencer reblogged this · 7 months ago -

elegantpeanutinfluencer liked this · 7 months ago

elegantpeanutinfluencer liked this · 7 months ago -

cupoftithi reblogged this · 7 months ago

cupoftithi reblogged this · 7 months ago -

wanderingmultiverse reblogged this · 7 months ago

wanderingmultiverse reblogged this · 7 months ago -

damphaired reblogged this · 7 months ago

damphaired reblogged this · 7 months ago -

legally-baby liked this · 7 months ago

legally-baby liked this · 7 months ago -

gingertomcat reblogged this · 7 months ago

gingertomcat reblogged this · 7 months ago -

gingertomcat liked this · 7 months ago

gingertomcat liked this · 7 months ago

she/her ▪︎ my mind; little organization

177 posts