Zelo-ref

More Posts from Zelo-ref and Others

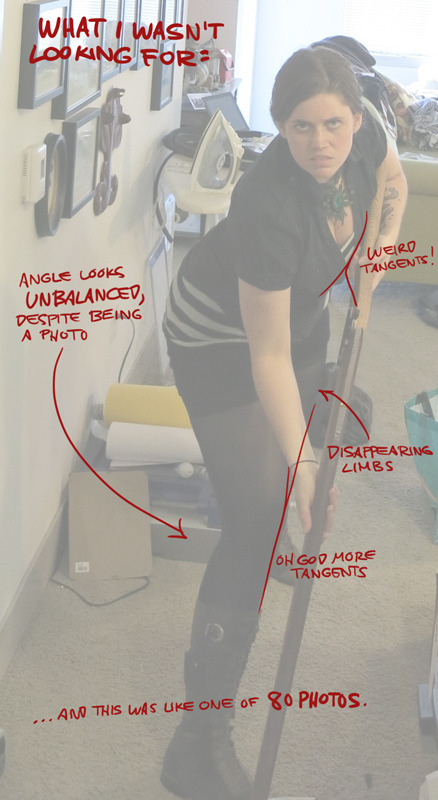

So I was chatting with the lovely Justin Oaksford yesterday, and he casually asked if I used photo reference for my recent Rolemodels piece- not as a bad thing, but because the pose and the camera angle read well. Pretty sure I grinned like an idiot when he brought it up because, goddammit, I’m proud that the work shows! I’ve felt like my work has been somewhat stilted as of late- I could feel myself subconsciously trending towards easier angles, easier poses, easier expressions just because it's slightly less frustrating for my brain to process- so getting that confirmation from a colleague was pretty damn satisfying.

I think there’s a tendency for artists to take pride in being able to draw out of your head, and, while that’s an admittedly important skill, what’s actually important is what that skill implies- it implies that you’ve internalized reference. That you’ve spent so much time looking at the world around you, studying it, drawing from it, breaking it down, that you’ve amassed an extensive mental library that you can draw from. You are Google reborn in the shallow husk of a human being.

But heck, the world’s a big place- what are the chances that you ever get to a point that you’ve internalized all of it? Internalized it AND ALSO are never going to forget it ever? Probably no chance at all. Sorry buddy. So rather than bemoaning the fact that we don’t have impenetrable search engine cyborg brains- yet- you sure as hell better still be using reference to fill in/refresh those empty shelves in your mental library. You shouldn’t have worm-ridden books about dinosaur anatomy from the 60’s in there. Stegosauruses with brains in their tails? CLEAN THAT SHIT OUT.

So my general process for using reference of any sort is:

loose thumbnails and brainstorming. If you have an idea, get that raw thing- unadulterated in it’s potential shittiness- onto paper. Good art is a combination of both instinct and discipline, so you don’t want to entirely discount those lightning strikes of brilliance. Or idiocy. Happens to all of us.

research and reference. Start gathering and internalizing whatever reference is pertinent to your piece- could be diagrams, art, photos, good old-fashioned READIN’, whathaveyou. Please note that this doesn’t mean find one picture of a giraffe- this means find tons of photos of giraffes, read about giraffes, understand giraffes, and learn how to incorporate that knowledge into your art with purpose and intent (Justin uses the word “intent” a lot so I’m stealing it). Don’t blindly copy what you see, but understand how to integrate it in an interesting and informed manner.

studies and practice. Could be lumped in with the previous step, granted, but it’s worth reiterating- if you’re drawing something new, it’s worth doing some studies. You discover things that you wouldn’t otherwise by just staring at them. It’s weird how I’m still learning this- “Gee golly, six-shooters are way easier to draw now that I’ve drawn a ton of them!” Yes wow Claire BRILLIANT. Gold star.

go for the gold. Finally, I’m sure it goes without saying, you integrate all of that research and knowledge into your initial thumbnails. If you learned something about anatomy, or fashion, or color, or butts, now you can drastically improve your original idea with this newfound knowledge. Also, per the images above, this is also your chance to improve on the reference- photos are a fantastic tool, but trust your instincts. Cameras can’t make informed decisions.

…So that’s my soapbox- it’s pretty easy, and it’s totally worth it. Research and reference lets you stand on the shoulders of giants- it lends legitimacy, specificity, and allure to your work that wouldn’t be there if you were just drawing out of your head 100% of the time. To put it simply- it makes your work ownable. It makes you stand out.

It makes you a better artist. :)

-C

It seems like all of the resources I can easily find online for identifying wolves vs dogs are either massive and difficult to understand without prior knowledge of the subject, or extremely bare-bones and miss a lot of key information. I tried to hit a comfortable middle-ground. (sorry if it’s a little wordy) This tutorial is made as a reference for drawing, so everything but purely visual differences between dogs and wolves have been left out. I’ve been wanting to make this for a while now, so I’m glad I finally sat down and did it! **EDIT** When it comes to the section on wolfdogs, please take it with a grain of salt. With something as complicated as genetics, they are of course, not going to be as simple as I make it seem. What features different levels of content can display, and even which percentages designate which levels of content are often hotly debated within the wolfdog community. At this point I’ve elected not to change the image set itself because: a. it’s a huge pain in the ass b. this is a tutorial for beginning artists. It’s meant to be a hugely simplified version of the topic, and I’ve stated clearly that it is NOT to be used in real-world identification. ((Huge thanks to yourdogisnotawolf. who’s blog inspired me to make this and for digging up that amazing picture of the wolf/lab mix))

Day dress, 1860′s

From the Museo de la Moda via the Museo del Romanticismo on Twitter

A visual dictionary of Boots

More Visual Glossaries (for Her): Backpacks / Bags / Bobby Pins / Bra Types / Hats / Belt knots / Chain Types / Coats / Collars / Darts / Dress Shapes / Dress Silhouettes / Eyeglass frames / Eyeliner Strokes / Hangers / Harem Pants / Heels / Lingerie / Nail shapes / Necklaces / Necklines / Patterns (Part1) / Patterns (Part 2) / Puffy Sleeves / Scarf Knots / Shoes / Shorts / Silhouettes / Skirts / Tartans / Tops / Underwear / Vintage Hats / Waistlines / Wedding Gown Silhouettes / Wool

-

prettierecho reblogged this · 2 years ago

prettierecho reblogged this · 2 years ago -

budugu liked this · 2 years ago

budugu liked this · 2 years ago -

pink-popcorn reblogged this · 5 years ago

pink-popcorn reblogged this · 5 years ago -

your-tiny-love reblogged this · 6 years ago

your-tiny-love reblogged this · 6 years ago -

surrenderdorothyy reblogged this · 6 years ago

surrenderdorothyy reblogged this · 6 years ago -

pipius reblogged this · 6 years ago

pipius reblogged this · 6 years ago -

marcevs liked this · 6 years ago

marcevs liked this · 6 years ago -

pipius liked this · 6 years ago

pipius liked this · 6 years ago -

theconglomeration reblogged this · 6 years ago

theconglomeration reblogged this · 6 years ago -

theotherstars reblogged this · 6 years ago

theotherstars reblogged this · 6 years ago -

henneberry liked this · 6 years ago

henneberry liked this · 6 years ago -

rainwashedsoul reblogged this · 6 years ago

rainwashedsoul reblogged this · 6 years ago -

naivara reblogged this · 6 years ago

naivara reblogged this · 6 years ago -

seancecafe liked this · 6 years ago

seancecafe liked this · 6 years ago -

felicemastronza reblogged this · 6 years ago

felicemastronza reblogged this · 6 years ago -

useitagain liked this · 6 years ago

useitagain liked this · 6 years ago -

wanderingcarmen liked this · 6 years ago

wanderingcarmen liked this · 6 years ago -

saprila reblogged this · 6 years ago

saprila reblogged this · 6 years ago -

22ehope reblogged this · 6 years ago

22ehope reblogged this · 6 years ago -

22ehope liked this · 6 years ago

22ehope liked this · 6 years ago -

bookishpredilections-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago

bookishpredilections-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago -

radioblueheart reblogged this · 6 years ago

radioblueheart reblogged this · 6 years ago -

reinadelrey reblogged this · 6 years ago

reinadelrey reblogged this · 6 years ago -

reinadelrey liked this · 6 years ago

reinadelrey liked this · 6 years ago -

keatonsbuster reblogged this · 6 years ago

keatonsbuster reblogged this · 6 years ago -

keatonsbuster liked this · 6 years ago

keatonsbuster liked this · 6 years ago -

running-wayfarer reblogged this · 6 years ago

running-wayfarer reblogged this · 6 years ago -

automaticbeargoopcash liked this · 6 years ago

automaticbeargoopcash liked this · 6 years ago -

zirekilefalls reblogged this · 6 years ago

zirekilefalls reblogged this · 6 years ago -

jackoffwithjill reblogged this · 6 years ago

jackoffwithjill reblogged this · 6 years ago -

prettylittledestroyer reblogged this · 6 years ago

prettylittledestroyer reblogged this · 6 years ago -

mourningcoughee reblogged this · 6 years ago

mourningcoughee reblogged this · 6 years ago -

mourningcoughee liked this · 6 years ago

mourningcoughee liked this · 6 years ago -

founopou-blog liked this · 6 years ago

founopou-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

adnillongoria liked this · 6 years ago

adnillongoria liked this · 6 years ago -

afangirls reblogged this · 6 years ago

afangirls reblogged this · 6 years ago -

kaiju-jesus reblogged this · 6 years ago

kaiju-jesus reblogged this · 6 years ago