Death Never Brought Itself Onto Her, But She Noted How It Always Felt Like A Distant Memory.

Death never brought itself onto her, but she noted how it always felt like a distant memory.

Maybe she had died once before—death at the hands of an executioner for her vile felonies that she was lucky to have only been imprisoned for, or at the hands of her own, the rich heiress with a family heirloom using her breast as a sheath she had buried there. Maybe, once, she’d seen death, seen his skeletal hands and his shrouded face and the infamous scythe to steal her soul and escort her onto the next host body as if she were a parasite. The baby she’d inhabit until death, when she was reunited with what would feel like her one and only true love, the only love she’d ever really know as she continued to cycle back to him and be in his arms once again.

Or maybe she was a new soul. A soul fresh from the womb of her mother, a fire forged and made to burn hot until the day she fizzled out into the cold hands of the being she’d like to envision as friendly and be forever trapped in the abyss of nothing, wandering in a place that certainly wasn’t Hell but did not match the stories of Heaven with the gates or whatever God or gods there were or the familiar faces of family and friends long since passed.

‘where lucia died’ tagslist: @theforgottencoolkid @vandorens @whorizcn @alicekaiba @evergrcen @goldbonne @babeineauxs @the-writers-blocks @suswriting @lucamused @noloumna @shezadis @semblanche @emdrabbles @sapphospouse @waterfallofinkandpages @calfromzeroday @andinbetweenwegarden @aphteavanawrites @bbabyapollo @hillelf @milkyway-writes @the-introvert-cafe | ask to be added/removed

More Posts from Yourwriters and Others

weird thing about writing is that like, even if no one decides to rep me and I don't get published and don't become a bestseller, if not one of those things happen, I've still got the book. I still have the story. It's a thing that you don't have to commit your entire life to but that you never have to give up if you don't want to.

it's just ingrained in my head that I will never stop writing, regardless of whether I'm empirically successful or not, cuz it's not about the success. It's always been about the stories.

The Strength of a Symmetrical Plot

One of my favorite studies of Harry Potter is that of the ring composition found both in the individual novels and overall composition. That very composition is what makes Harry Potter such a satisfying story. It’s a large part of the reason Harry Potter is destined to become a classic.

And it’s an integral part of the series many people are completely unaware of.

So what is ring composition?

It’s a well-worn, beautiful, and (frankly) very satisfying way of structuring a story. John Granger, known online as The Hogwarts Professor, has written extensively on it.

Ring Composition is also known as “chiastic structure.” Basically, it’s when writing is structured symmetrically, mirroring itself: ABBA or ABCBA.

Poems can be structured this way. Sentences can be structured this way. (Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.) Stories of any length and of any form can be structured this way.

In a novel, the basic structure depends on three key scenes: the catalyst, the crux, and the closing.

The catalyst sets the story into the motion.

The crux is the moment when everything changes. (It is not the climax).

The closing, is both the result of the crux and a return to the catalyst.

In Harry Potter, you might recognise this structure:

Voldemort casts a killing curse on Harry and doesn’t die.

Voldemort attempts to come back to power

Voldemort comes back to power.

Harry learns what it will take to remove Voldemort from power.

Voldemort casts a killing curse on Harry and dies.

But all stories should have this structure. A book’s ending should always reference its beginning. It should always be the result of some major turning point along the way. Otherwise, it simply wouldn’t be a very good story.

What’s most satisfying about chiastic structure is not the basic ABA structure, but the mirroring that happens in between these three major story points.

To illustrate what a more complicated ABCDEFGFEDCBA structure looks like, (but not as complicated as Harry Potter’s, which you can see here and here) Susan Raab has put together a fantastic visual of ring composition in Beauty and the Beast (1991), a movie which most agree is almost perfectly structured.

source: x

What’s so wonderful about ring composition in this story is that it so clearly illustrates how that one crucial decision of Beast changes everything in the world of the story. Everything from the first half of the story comes back in the second half, effected by Beast’s decision. This gives every plot point more weight because it ties them all to the larger story arc. What’s more, because it’s so self-referential, everything feels tidy and complete. Because everything has some level of importance, the world feels more fully realized and fleshed out. No small detail is left unexplored.

How great would Beauty and the Beast be if Gaston hadn’t proposed to Belle in the opening, but was introduced later on as a hunter who simply wanted to kill a big monster? Or if, after the magnificent opening song, the townspeople had nothing to do with the rest of the movie? Or if Maurice’s invention had never been mentioned again after he left the castle?

Humans are nostalgic beings. We love returning to old things. We don’t want the things we love to be forgotten.

This is true of readers, too.

We love seeing story elements return to us. We love to know that no matter how the story is progressing, those events that occurred as we were falling in love with it are still as important to the story itself as they are to us. There is something inside us all that delights in seeing Harry leave Privet Dr. the same way he got there–in the sidecar of Hagrid’s motorbike. There’s a power to it that would make any other exit from Privet Dr. lesser.

On a less poetic note, readers don’t like to feel as though they’ve wasted their time reading about something, investing in something, that doesn’t feel very important to the story. If Gaston proposed to Belle in Act 1 and did nothing in Act 3, readers might ask “Why was he even in the movie then? Why couldn’t we have spent more time talking about x instead?” Many people do ask similar questions of plot points and characters that are important in one half of a movie or book, but don’t feature in the rest of it.

Now, ring composition is odiously difficult to write, but even if you can’t make your story a perfect mirror of itself, don’t let story elements leave quietly. Let things echo where you can–small moments, big moments, decisions, characters, places, jokes.

It’s the simplest way of building a story structure that will satisfy its readers.

If there’s no place for something to echo, if an element drops out of the story half-way through, or appears in the last act, and you simply can’t see any other way around it, you may want to ask yourself if it’s truly important enough to earn its place in your story.

Further reading:

If you’d like to learn more about ring theory, I’d recommend listening to the Mugglenet Academia episode on it: x

You can also read more about symmetry in HP here: x

And more about ring structure in Lolita and Star Wars here: x and x

And about why story endings and beginnings should be linked here: x

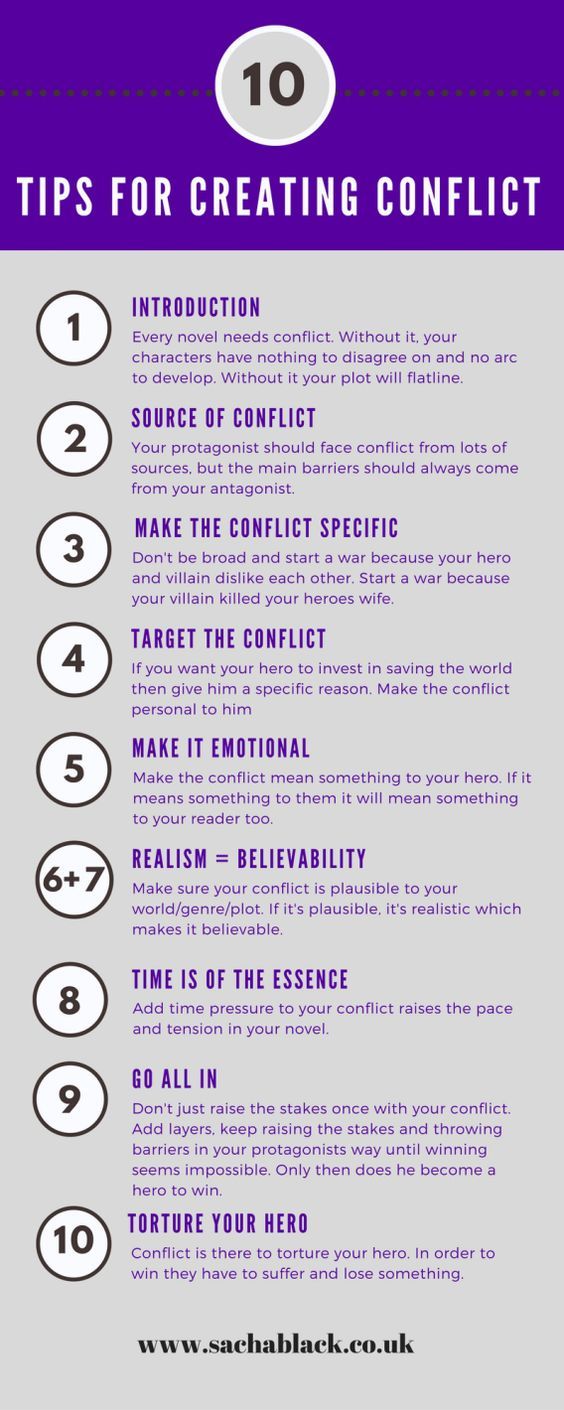

About Conflict by Sacha Black

anyway most writing advice is frequently contradictory to other writing advice you might receive from people who have just as much/more writing ~expertise~ and a lot of writing advice is just flat-out terrible even if it’s coming from an ~expert~ so if you’re a writer consider this post a reminder that

writing advice that comes up on your dash should be looked at as tips you can choose to follow or discard as it suits you, not hardline rules you MUST abide by or else you’re a ‘bad writer’

you’re allowed to look at a piece of writing advice and say, “wow, that’s a shit idea and i don’t want write like that” and forget about it – even if the post has thousands of notes full of other people agreeing with it

there is no One True Right Way to write, your writing does not have to be just like everyone else’s – if all stories were written the same way and with the same style, reading would be a much more boring thing to do

if you try to write in a way that pleases everyone, you will fail because pleasing everyone is not possible – your own satisfaction with your work, your own desire to write a story, and your own enjoyment of writing are more important than that

Never Confuse Characterization for Character

Lately I’ve been revisiting Story by Robert McKee, a famous book on the craft of storytelling. It can be pretty intense and heavy at times, so it’s not something I would recommend for beginners. In fact, the first time I read it, a lot of it was so deep and new that it went over my head. It’s been interesting reading it again. Now, parts seem to be validating my ideas, rather than turning and twisting them.

One thing in particular stuck out to me this last week: character vs. characterization.

Regularly, I see writers hyperfocused on characterization.

Characterization is all the surface or near-surface stuff: voice, demeanor, likes and dislikes, hair and eye color, clothes, habits, etc.

Honestly, I personally consider these things to be part of character, but for the sake of this post, we are going to look at them as two different things, to communicate specific ideas.

Characterization can be really important and really effective. Give us the right voice, mannerisms, and appearance, and we can instantly be drawn to someone. Jack Sparrow is a good example. Johnny Depp combined Pepe le Pew with Keith Richards to come up with a unique, iconic characterization. In fact, Depp is often very good with characterization. A lot of actors have the same demeanor for all of their characters (I’m trying so hard to not name anyone in particular right now), but Depp’s Jack Sparrow, Mad Hatter, Willy Wonka, Grindelwald, Mort Rainey, etc. all have unique characterizations.

You are very familiar with characterization. All over online you can find long questionnaires to fill out to get to know your protagonist (or any other character). Back in the day, I would fill these out because they were fun (and they are, and that’s okay!), but I often found that despite how personal the questions could get (i.e. “What is his/her greatest fear?”), I wasn’t quite satisfied with the person on the page, not to mention that a lot of the stuff I ended up brainstorming seemed irrelevant to the story. And in some cases, I had to change what I’d filled out to write a better story “for some reason.”

I’ve actually heard/read a few writers get on the character vs. characterization bandwagon and go on to kind of … knock down characterization. I don’t agree with that. I strongly believe in the power of rich characterization. And I have zero problems if you want to be like Johnny Depp and give each main character a super unique demeanor. In fact, as long as it doesn’t get too outlandish for your world, I enjoy that and think it is a good idea.

After all, if Jack Sparrow had a demeanor like the Mad Hatter, Pirates would be totally different.

But here is the problem that past me, and I see a lot of writers run into, characterization is not the sum of character. You might be filling out questionnaire after questionnaire, trying to find The Thing™️, but it’s not coming together, because you only know about characterization.

Characterization is part of a character, but it isn’t fully “character.” When it gets down to it, when you want to get really, really deep, characterization isn’t going to get you there.

As J.K. Rowling famously wrote, it’s our choices that determine who we are.

You can be the gothiest goth kid, or the preppiest prep kid, but who you truly are is what you choose to do, and perhaps, I would probably add, why you choose to do it. When encountering a stray dog, do you kick it away or give it some food? You can cut out all the external stuff; you can cut out the hairstyle, the age, the clothes, the likes and dislikes, and at the heart of it, is choices.

But it’s not just any choice.

As Robert McKee and others have stated, to get into that inner gem of character, it’s the choices the character makes when there are significant stakes. If a character chooses vanilla ice cream over chocolate, that doesn’t really tell me a lot, unless I want to read symbolism into it (which could be there).

Maybe your protagonist tells the truth to his parents about putting a frog in his sister’s bed. Does that really matter if there are no potential consequences involved? Telling the truth when there are no dire consequences is easy. Telling the truth when there are important things at stake is harder. What if telling the truth meant he would be grounded and could not participate in a talent show he’s been practicing for, for months? There is prize money involved, and he was hoping to use that money to buy a chemistry set. Chemistry is his passion and he wants be a world-renowned chemist someday. Which is more important to him? A potential chemistry set or telling the truth?

This can be a great way to add depth. Well, it is depth. Especially if their characterization seems to be at odds with who they truly are. A vampire who craves human blood but chooses not to drink it is interesting. A prince who’d rather be a beach bum is interesting. The bully who, when it gets down to it, sticks up for an enemy is interesting. It makes them more complex. It draws us in so we want to know more. Why doesn’t this vampire drink human blood? Why doesn’t this prince want to be a king? Why did this bully stick up for someone? The answers to those questions makes them complex.

We all have layers after all. And we all have boundaries. I almost never lie. But if I was stuck between telling the truth or lying to save a loved one’s life, well, I’d pick the latter. But if I picked the former, that would say a lot about me as well.

Some writers throw in contradictions to create character depth (a vampire who refuses to drink human blood), which works, but if it’s a main character, and I never get an idea or hint of the “why,” I sometimes find myself feeling … cheated. Like it was just thrown in (and maybe it was). I also then get stuck, fixated on the why that I never get, so it’s distracting. I don’t know that we always need to explore the why, but I would say for main characters, it’s almost always more effective, more powerful, more meaningful, to address the why, to some extent. Unless, of course, the reason is ridiculous, in which case, maybe you need to reevaluate that and come up with something better.

There is an important part to all of this, which is that we need to see your character making significant choices, which means they must be placed in situations where they can make decisions. If you don’t give your character opportunities to make significant decisions, it’s probably going to be a problem. This is another reason why people ask for “active” protagonists. They must want something and make choices with stakes attached.

Don’t be afraid to make your protagonist’s true self a bit negative or flawed–after all, they need to grow during the story (usually). Maybe near the beginning of the story, you show your character being selfish, but at the end, we see he is willing to sacrifice his life, literally or figuratively. This is called character arc.

The way your character changes through the course of the story can also bring more “character” to him or her than characterization can alone. If we have a character that starts as a villain, but ends up being a good guy by the end, well, that’s interesting and complex, and the transformation demands depth to be satisfying. This can all get more complicated real fast, because there are degrees and variations, and I don’t want to muddy the water quite yet.

But if you are only trying to find character by filling out endless characterization questionnaires, you might never write a fully formed, deep, complex character. Instead, consider choices, contradictions, and arcs.

Are You Using Too Much Stage Direction?

Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, we don’t need to know that someone crossed the room, reached for the coffee cup, turned sideways, took a step forward, or glanced to the left.

Visual writers have an especially hard time with this (fiction writers who “see” their story in their head, and write down the images blow-for-blow, as though narrating a movie).

There’s nothing wrong with this writing process, of course. Just know that you’ll be more prone to adding excessive, pointless movements to your novel or short story.

Then, when revising, ask yourself if they are important to the story (sometimes, it is important that someone took a step forward!) and take out the ones that aren’t. Or, better yet, delete them all, then put back only the ones that have left holes in their absence.

Remember, stage direction is different from meaningful gesture or action.

Meaningful gestures and actions can orient the reader or give information about character or plot.

Stage direction, by my definition, is pointless movement.

Here is an original excerpt from Haruki Murakami’s Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World to illustrate my point.

“See anyone milling around in the hall?” I asked. “Not a soul,” she said. I undid the chain, let her in, and quickly relocked the door. “Something sure smells good,” she said. “Mind if I peek in the kitchen?” “Go right ahead. But are you sure there aren’t any strange characters hanging around the entrance? No one doing street repairs, or just sitting in a parked car?” “Nothing of the kind,” she said, plunking the books down on the kitchen table. Then she lifted the lid of each pot on the range. “You make all this yourself?”

Here, we get just enough to orient us–we know the woman was outside the apartment, she walked into the house, went into the kitchen, and the narrator followed her there. But Murakami doesn’t actually say that. He allows us to infer those movements from the dialogue and the light peppering of action and description.

Now, here is the same excerpt re-written with way too much stage direction:

Lees verder

Thanks to @inkingfireplace for tagging me!

1. Name: Anthea

2. Nickname: Ann

3. Star Sign: scorpio

4. Prefered pronouns: she/her

5. Sexuality: lesbian

6. Favourite Color: blue

7. Time Right Now: 14:59

8. Average Hours of Sleep: seven hours

9. Lucky Number(s): nine

10. Last Thing I Googled: corona universities

11. Number of Blankets: one

12. Favourite Fictional Character: Luna Lovegood

13. What are you wearing: green jeans and a grey sweater

14. Favorite Book: Aristotle and Dante discover the secrets of the universe by Benjamin Alire Saénz

15. Favorite Musician(s): Coldplay, Muse, Racoon, U2

16. Dream Job: astrophysicist or writer

17. Number of Followers: 33

18. When Did You Create Your Blog: a few months ago

19. What Do You Mostly Post: things about my wips or about writing in general

20. What Made You Decide to Get a Tumblr: I thought it would be fun

21. When Did Your Blog Reach Its Peak: not yet I guess

22. Do You Get Asks on a Daily Basis: no

23. Why Did You Choose Your URL: I wanted a username related to writing and this one wasn’t taken yet.

Tagging: @dowings, @myhusbandsasemni, @poeticparchment, @inklingsoflaura, @epicpoetry

I love that excerpt!

cocaine, a car wreck, and an apple pie recipe.

a modern retelling of sophocles’ ajax, wintersong is 18-year-old and terribly wayward hollis knox’s aching love letter to all the good in the world: grocery store aisles’ uneven green-and-white flecked tiles, shared secrets behind calloused hands, and little brothers’ sunday morning swim meets. all the good that atrophies too fast.

goal words: 50,000

current words: 21,000

weheartit board

here’s an excerpt from the first chapter:

let me know what you think!

p.s. i follow from studylikeathena.

I’m wondering, how do I come up with good ideas to write a sub-plot that actually fits into the story and won’t make the reader lose the connection with the main plot?

How to Write A Sub Plot

If you look back on every single bestselling book ever printed, the chances are that most, if not all of them, contain sub-plots.

A sub-plot is part of a book that develops separately from the main story, and it can serve as a tool that extends the word count and adds interest and depth into the narrative.

Sub-plots are key to making your novel a success, and, although they aren’t necessary for shorter works, are an essential aspect of story writing in general.

However, sub-plots can be difficult to weave into the main plot, so here are a few tips on how to incorporate sub-plots into your writing.

1. Know Your Kinds of Sub-Plots and Figure Out Which is Best For Your Story

Sub-plots are more common than you think, and not all of them extend for many chapters at a time.

A sub-plot doesn’t have to be one of the side characters completely venturing off from the main group to struggle with their own demons or a side quest that takes up a quarter of the book. Small things can make a big difference, and there are many of these small things that exist in literature that we completely skip over when it comes to searching for sub-plots.

Character Arcs

Character arcs are the most common sub-plot.

They show a change in a dynamic character’s physical, mental, emotional, social, or spiritual outlook, and this evolution is a subtle thing that should definitely be incorporated so that the readers can watch their favorite characters grow and develop as people.

For example, let’s say that this guy named Bob doesn’t like his partner Jerry, but the two of them had to team up to defeat the big bad.

While the main plot involves the two of them brainstorming and executing their plans to take the big bad down, the sub-plot could involve the two getting to know each other and becoming friends, perhaps even something more than that.

This brings me to the second most common sub-plot:

Romance

Romance can bolster the reader’s interest; not only do they want to know if the hero beats the big bad guy, they also want to know if she ends up with her love interest in the end or if the warfare and strife will keep them apart.

How to Write Falling in Love

How to Write a Healthy Relationship

How to Write a Romance

Like character arcs, romance occurs simultaneously with the main plot and sometimes even influences it.

Side-Quests

There are two types of side-quest sub-plots, the hurtles and the detours.

Hurdle Sub-Plots

Hurdle sub-plots are usually complex and can take a few chapters to resolve. Their main purpose is to put a barrier, or hurdle, between the hero and the resolution of the main plot. They boost word count, so be careful when using hurdle sub-plots in excess.

Think of it like a video game.

You have to get into the tower of a fortress to defeat the boss monster.

However, there’s no direct way to get there; the main door is locked and needs to have three power sources to open it, so you have to travel through a monster-infested maze and complete all of these puzzles to get each power source and unlock the main door.

Only, when you open the main door, you realize that the bridge is up and you have to find a way to lower it down and so forth.

Detour Sub-Plot

Detour sub-plots are a complete break away from the main plot. They involve characters steering away from their main goal to do something else, and they, too, boost word count, so be careful not too use these too much.

Taking the video game example again.

You have to get to that previously mentioned fortress and are on your way when you realize there is an old woman who has lost her cattle and doesn’t know what to do.

Deciding the fortress can wait, you spend harrowing hours rounding up all of the cows and steering them back into their pen for the woman.

Overjoyed, the woman reveals herself to be a witch and gives you a magical potion that will help you win the fight against the big bad later.

**ONLY USE DETOUR SUB-PLOTS IF THE OUTCOME HELPS AID THE PROTAGONISTS IN THE MAIN PLOT**

If they’d just herded all of the cows for no reason and nothing in return, sure it would be nice of them but it would be a complete waste of their and the readers’ time!

2. Make Sure Not to Introduce or Resolve Your Sub-Plots Too Abruptly

This goes for all sub-plots. Just like main plots, they can’t be introduced and resolved with a snap of your fingers; they’re a tool that can easily be misused if placed into inexperienced hands.

Each sub-plot needs their own arc and should be outlined just like how you outlined your main plot.

How to Outline Your Plot

You could use my methods suggested in the linked post, or you could use the classic witch’s hat model if you feel that’s easier for something that’s less important than your main storyline.

3. Don’t Push It

If you don’t think your story needs a sub-plot, don’t add a sub-plot! Unneeded sub-plots can clutter up your narrative and make it unnecessarily winding and long.

You don’t have to take what I’m saying to heart ever!

It’s your story, you write it how you think it should be written, and no one can tell you otherwise!

Hope this Helped!

-

the-orangeauthor liked this · 3 years ago

the-orangeauthor liked this · 3 years ago -

hay-389 liked this · 3 years ago

hay-389 liked this · 3 years ago -

andinbetweenwegarden reblogged this · 3 years ago

andinbetweenwegarden reblogged this · 3 years ago -

jazbotwritesff-blog liked this · 5 years ago

jazbotwritesff-blog liked this · 5 years ago -

aleja120403 liked this · 5 years ago

aleja120403 liked this · 5 years ago -

yourwriters reblogged this · 5 years ago

yourwriters reblogged this · 5 years ago -

puffiat liked this · 5 years ago

puffiat liked this · 5 years ago -

gh0stfacecg liked this · 5 years ago

gh0stfacecg liked this · 5 years ago -

marissacatcreates liked this · 5 years ago

marissacatcreates liked this · 5 years ago -

silviearitani liked this · 5 years ago

silviearitani liked this · 5 years ago -

ophiaihel reblogged this · 5 years ago

ophiaihel reblogged this · 5 years ago -

lukawriting reblogged this · 5 years ago

lukawriting reblogged this · 5 years ago -

lethimrunsonia liked this · 5 years ago

lethimrunsonia liked this · 5 years ago -

the-introvert-cafe liked this · 5 years ago

the-introvert-cafe liked this · 5 years ago -

luamused liked this · 5 years ago

luamused liked this · 5 years ago -

vandorens-archive reblogged this · 5 years ago

vandorens-archive reblogged this · 5 years ago -

sapphospouse liked this · 5 years ago

sapphospouse liked this · 5 years ago -

hillelf reblogged this · 5 years ago

hillelf reblogged this · 5 years ago -

adaughterofathena liked this · 5 years ago

adaughterofathena liked this · 5 years ago -

howdywrites reblogged this · 5 years ago

howdywrites reblogged this · 5 years ago -

docmartinobsessed liked this · 5 years ago

docmartinobsessed liked this · 5 years ago -

owlfly liked this · 5 years ago

owlfly liked this · 5 years ago -

mythwords liked this · 5 years ago

mythwords liked this · 5 years ago -

occeansun liked this · 5 years ago

occeansun liked this · 5 years ago -

fiddler-unroofed liked this · 5 years ago

fiddler-unroofed liked this · 5 years ago -

howdywrites liked this · 5 years ago

howdywrites liked this · 5 years ago -

nallthatjazz liked this · 5 years ago

nallthatjazz liked this · 5 years ago -

aphteavanawrites reblogged this · 5 years ago

aphteavanawrites reblogged this · 5 years ago -

aphteavana liked this · 5 years ago

aphteavana liked this · 5 years ago