Curate, connect, and discover

Sustainable Architecture - Blog Posts

10knotes:

architizer:

For the last 500 years, the locals of Nongriat in Meghalaya, India have grown several hundred bridges across the region’s numerous water channels, using just the roots of local ribber trees. Some of the bridges extend over 100 feet in length and are strong enough to support more than 50 people at a time.

This is beautiful; I hope to one day see this. Traveling to India has been on my list of places to go since I was a child anyways.

i remember the heat like i remember my own name.

i live in florida now, mind u, so im not unfamiliar with the heat but...it's a different kind of heat.

men carrying water jugs over to the local mercado to refill for their homes, sometimes making five or more trips to do so, because sometimes the running water in the favelas either stops working or runs dirty, and the sweating from the weather is not a scent u want ur house to be filled with. families walking around the city covering themselves with parasols and cobertorinhos to buy groceries and whatnot. children running down to the river to bathe and swim not necessarily just for fun but because that was the only way to cool down. women hanging up wet clothes to dry between as varandas das ruas, sitting shirtless on their balconies because inside is almost hotter. our seasons are different from North America's because they are switched around, so "winter" hits in June/July/August for us -- it's very similar to florida though, in the sense that we pretty much have two seasons -- summer and less summer. i have vivid memories of running down to the beach with my cousins in my father's hometown of Iguape, just outside of São Paulo, naked as the day we were born and jumping into the sea to feel the cool relief away from the blazing heat.

this heat has killed over 48,000 people (source link) from 2000-2018, and climate change is only going to make it worse. in 2023, the country recorded its hottest temperature ever at 44.8°C -- that is 112.6°F. in g20climaterisks.org's article recounts a study done about climate change and its impact in Brasil in a projected 2050-2100 timeline - the study predicts heat wave/heat-related excess deaths will increase by 854%. when Gomes da Silva describes the feeling of being able to breathe again, it is no exaggeration.

green roofs have been around since the 60s, its nothing new. in fact, as Cassiano said, what would be considered the Brasilian "1%" has already planned and built homes with green roofs and has been doing so for quite a while. it has taken this long to get to a point where it's semi-accessible to the general public, and it does not cost as much to us in the US as it does to those in Brasil -- this is an amazing development but there is still more work to be done. for example, this spring is odd to floridians since it feels like its fucking July, but thats because florida's in a fucking drought right now -- there have been 17 wildfires as of April 22nd, only one of which that was contained (and only 70% contained at that). green roofs wouldnt kill the problem entirely, but i would really like to see this or some version of this in the United States while i'm still living.

Pictured: Luis Cassiano is the founder of Teto Verde Favela, a nonprofit that teaches favela residents in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, how to build their own green roofs as a way to beat the heat. He's photographed at his house, which has a green roof.

Article

"Cassiano is the founder of Teto Verde Favela, a nonprofit that teaches favela residents how to build their own green roofs as a way to beat the heat without overloading electrical grids or spending money on fans and air conditioners. He came across the concept over a decade ago while researching how to make his own home bearable during a particularly scorching summer in Rio.

A method that's been around for thousands of years and that was perfected in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s, green roofs weren't uncommon in more affluent neighborhoods when Cassiano first heard about them. But in Rio's more than 1,000 low-income favelas, their high cost and heavy weight meant they weren't even considered a possibility.

That is, until Cassiano decided to team up with a civil engineer who was looking at green roofs as part of his doctoral thesis to figure out a way to make them both safe and affordable for favela residents. Over the next 10 years, his nonprofit was born and green roofs started popping up around the Parque Arará community, on everything from homes and day care centers, to bus stops and food trucks.

When Gomes da Silva heard the story of Teto Verde Favela, he decided then and there that he wanted his home to be the group's next project, not just to cool his own home, but to spread the word to his neighbors about how green roofs could benefit their community and others like it.

Pictured: Jessica Tapre repairs a green roof in a bus stop in Benfica, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Relief for a heat island

Like many low-income urban communities, Parque Arará is considered a heat island, an area without greenery that is more likely to suffer from extreme heat. A 2015 study from the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro showed a 36-degree difference in land surface temperatures between the city's warmest neighborhoods and nearby vegetated areas. It also found that land surface temperatures in Rio's heat islands had increased by 3 degrees over the previous decade.

That kind of extreme heat can weigh heavily on human health, causing increased rates of dehydration and heat stroke; exacerbating chronic health conditions, like respiratory disorders; impacting brain function; and, ultimately, leading to death.

But with green roofs, less heat is absorbed than with other low-cost roofing materials common in favelas, such as asbestos tiles and corrugated steel sheets, which conduct extreme heat. The sustainable infrastructure also allows for evapotranspiration, a process in which plant roots absorb water and release it as vapor through their leaves, cooling the air in a similar way as sweating does for humans.

The plant-covered roofs can also dampen noise pollution, improve building energy efficiency, prevent flooding by reducing storm water runoff and ease anxiety.

"Just being able to see the greenery is good for mental health," says Marcelo Kozmhinsky, an agronomic engineer in Recife who specializes in sustainable landscaping. "Green roofs have so many positive effects on overall well-being and can be built to so many different specifications. There really are endless possibilities.""

Pictured: Summer heat has been known to melt water tanks during the summer in Rio, which runs from December to March. Pictured is the water tank at Luis Cassiano's house. He covered the tank with bidim, a lightweight material conducive for plantings that will keep things cool.

A lightweight solution

But the several layers required for traditional green roofs — each with its own purpose, like insulation or drainage — can make them quite heavy.

For favelas like Parque Arará, that can be a problem.

"When the elite build, they plan," says Cassiano. "They already consider putting green roofs on new buildings, and old buildings are built to code. But not in the favela. Everything here is low-cost and goes up any way it can."

Without the oversight of engineers or architects, and made with everything from wood scraps and daub, to bricks and cinder blocks, construction in favelas can't necessarily bear the weight of all the layers of a conventional green roof.

That's where the bidim comes in. Lightweight and conducive to plant growth — the roofs are hydroponic, so no soil is needed — it was the perfect material to make green roofs possible in Parque Arará. (Cassiano reiterates that safety comes first with any green roof he helps build. An engineer or architect is always consulted before Teto Verde Favela starts a project.)

And it was cheap. Because of the bidim and the vinyl sheets used as waterproof screening (as opposed to the traditional asphalt blanket), Cassiano's green roofs cost just 5 Brazilian reais, or $1, per square foot. A conventional green roof can cost as much as 53 Brazilian reais, or $11, for the same amount of space.

"It's about making something that has such important health and social benefits possible for everyone," says Ananda Stroke, an environmental engineering student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro who volunteers with Teto Verde Favela. "Everyone deserves to have access to green roofs, especially people who live in heat islands. They're the ones who need them the most." ...

It hasn't been long since Cassiano and the volunteers helped put the green roof on his house, but he can already feel the difference. It's similar, says Gomes da Silva, to the green roof-covered moto-taxi stand where he sometimes waits for a ride.

"It used to be unbearable when it was really hot out," he says. "But now it's cool enough that I can relax. Now I can breathe again."

-via NPR, January 25, 2025

Roof Extensions Deck in Melbourne Medium-sized, stylish backyard deck image with an addition to the roof

So oil is flowing since the beginning of this month. But people are still fighting. Here are some places you can help and donate:

Support camp migizi which is just an hour north of me st

I think we need to normalise trying to be sustainable. The amount of people who just don't care about the environment around them astounds me. Some people don't care that the $700 temu haul doesn't degrade because everything is made of plastic. They don't care that the tree they just dug up has been there longer than they have been alive. They don't care that most of the food they buy comes in plastic that hasn't been recycled and will take hundreds of years to degrade. They don't care about native fauna and flora that are going extinct.

We need more trees in suburban and urban areas. They create shade for people and habitat for wild life. In overdeveloped areas which are just flat Concrete and asphalt temperatures can get really high.

Also if ur going to have a lawn, please native grasses and plants because these give habitat to bees and native wildlife.

Plastic or fake grass can get hot enough to give third degree burns and is a danger to pets and children.

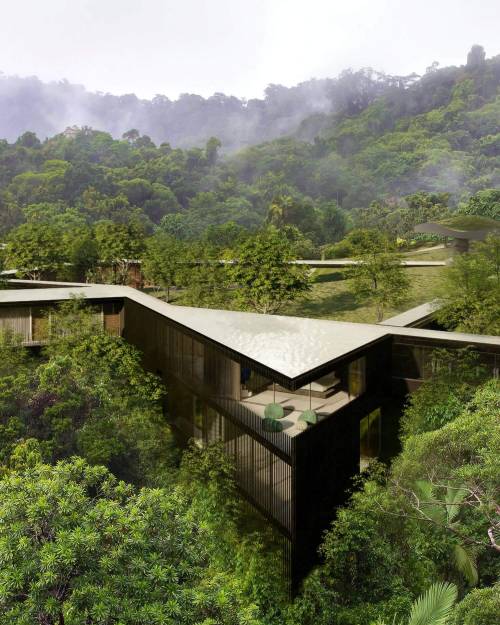

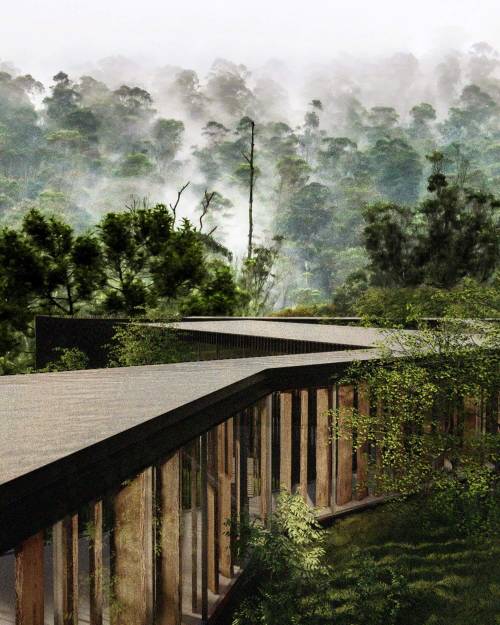

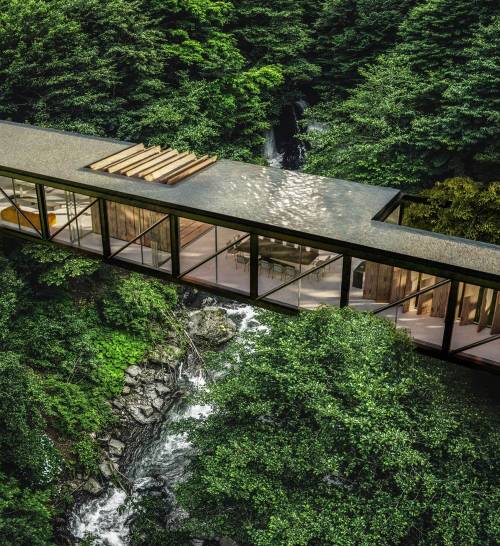

Farmhouse, Catargo, Costa Rica,

Tetro Arquitetura