Handwriting Demo Pt. 2

Handwriting Demo Pt. 2

I got a few requests to write down the alphabet in my “fancy writing” (and I promised another anon user that I would do this sometime this week)

I unfortunately don’t have much time (essay to write!!!), so I’ve quickly whipped up a short demo/really basic tutorial on 3 of the fonts I use the most.

LINED

CURSIVE

3-D BLOCK

(I apologise that the writing isn’t perfect; I was in a rush :(( Maybe I’ll do a more comprehensive tutorial later if people ask me to.)

Inbox me if you have any questions :)

-Gia

More Posts from Zelo-ref and Others

Day dress, 1860′s

From the Museo de la Moda via the Museo del Romanticismo on Twitter

This is what it’s like to go to an all-plus size, body positive pool party

After years of negative experiences at pool parties and the like, I was so excited to attend the 2nd Annual Golden Confidence Pool Party hosted by fashion blogger Essie Golden. This party wasn’t just about having a good time — it was about creating a space for women to feel good about their bodies.

Photos: Rick Jones

READ MORE

Jean Paul Gaultier, ss2007, Couture

I've been thinking about this for a while, but how effective is full plate armour? Was it actually a good way to defend yourself?

Short Answer: Yes.

Here’s a general rule: People in the past were ignorant about a lot of things, but they weren’t stupid. If they used something, chances are they had a good reason. There are exceptions, but plate armor is not one of them.

Long Answer:

For a type of armor, no matter what it is, to be considered effective, it has to meet three criteria.

The three criteria are: Economic Efficiency, Protectiveness, and Mobility.

1. Is it Economically Efficient?

Because of the nature of society in the Middle Ages, what with equipment being largely bring-it-yourself when it came to anybody besides arrowfodder infantry who’d been given one week of training, economic efficiency was a problem for the first couple of decades after plate armor was introduced in France in the 1360s. It wasn’t easy to make, and there wasn’t really a ‘science’ to it yet, so only the wealthiest of French soldiers, meaning knights and above, had it; unless of course somebody stole it off a dead French noble. The Hundred Years War was in full swing at the time, and the French were losing badly to the English and their powerful longbows, so there were plenty of dead French nobles and knights to go around. That plate armor was not very economically efficient for you unless you were a rich man, though, it also was not exactly what we would call “full” plate armor.

Above: Early plate armor, like that used by knights and above during the later 1300s and early 1400s.

Above: Two examples of what most people mean when they say “full” plate armor, which would have been seen in the mid to late 1400s and early 1500s.

Disclaimer: These are just examples. No two suits of armor were the same because they weren’t mass-produced, and there was not really a year when everybody decided to all switch to the next evolution of plate armor. In fact it would not be improbably to see all three of these suits on the same battlefield, as expensive armor was often passed down from father to son and used for many decades.

Just like any new technology, however, as production methods improved, the product got cheaper.

Above: The Battle of Barnet, 1471, in which everybody had plate armor because it’s affordable by then.

So if we’re talking about the mid to late 1400s, which is when our modern image of the “knight in shining armor” sort of comes from, then yes, “full” plate armor is economically efficient. It still wasn’t cheap, but neither are modern day cars, and yet they’re everywhere. Also similar to cars, plate armor is durable enough to be passed down in families for generations, and after the Hundred Years War ended in 1453, there was a lot of used military equipment on sale for cheap.

2. Is it Protective?

This is a hard question to answer, particularly because no armor is perfect, and as soon as a new, seemingly ‘perfect’ type of armor appears, weapons and techniques adapt to kill the wearer anyway, and the other way around. Early plate armor was invented as a response to the extreme armor-piercing ability of the English longbow, the armor-piercing ability of a new kind of crossbow, and advancements in arrowhead technology.

Above: The old kind of arrowhead, ineffective against most armor.

Above: The new kind of arrowhead, very effective at piercing chainmaille and able to pierce plate armor if launched with enough power.

Above: An arrow shot from a “short” bow with the armor-piercing tip(I think it’s called a bodkin tip) piercing a shirt of chainmaille. However, the target likely would have survived since soldiers wore protective layers of padding underneath their armor, so if the arrow penetrated skin at all, it wasn’t deep. That’s Terry Jones in the background.

Above: A crossbow bolt with the armor piercing tip penetrating deep through the same shirt of chainmaille. The target would likely not survive.

Above: A crossbow bolt from the same crossbow glancing off a breastplate, demonstrating that it was in fact an improvement over wearing just chainmaille.

Unfortunately it didn’t help at all against the powerful English longbows at close range, but credit to the French for trying. It did at least help against weaker bows.

Now for melee weapons.

It didn’t take long for weapons to evolve to fight this new armor, but rarely was it by way of piercing through it. It was really more so that the same weapons were now being used in new ways to get around the armor.

Above: It’s a popular myth that Medieval swords were dull, but they still couldn’t cut through plate armor, nor could they thrust through it. Your weapon would break before the armor would. Most straight swords could, however, thrust through chainmaille and anything weaker.

There were three general answers to this problem:

1. Be more precise, and thrust through the weak points.

Above: The weak points of a suit of armor. Most of these points would have been covered by chainmaille, leather, thick cloth, or all three, but a sword can thrust through all three so it doesn’t matter.

To achieve the kind of thrusting accuracy needed to penetrate these small gaps, knights would often grip the blade of their sword with one hand and keep the other hand on the grip. This technique was called “half-swording”, and you could lose a finger if you don’t do it right, so don’t try it at home unless you have a thick leather glove to protect you, as most knights did, but it can also be done bare-handed.

Above: Examples of half-swording.

2. Just hit the armor so fucking hard that the force carries through and potentially breaks bones underneath.

Specialty weapons were made for this, but we’ll get to them in a minute. For now I’m still focusing on swords because I like how versatile the European longsword is.

Above: A longsword. They’re made for two-handed use, but they’re light enough to be used effectively in one hand if you’d like to have a shield or your other arm has been injured. Longswords are typically about 75% of the height of their wielders.

Assuming you’re holding the sword pointing towards the sky, the part just above the grip is called the crossguard, and the part just below the grip is called the pommel. If you hold the sword upside-down by the blade, using the same careful gripping techniques as with half-swording, you can strike with either the crossguard or the pommel, effectively turning the sword into a warhammer. This technique was called the Murder Stroke, and direct hits could easily dent plate armor, and leave the man inside bruised, concussed, or with a broken bone.

Above: The Murder Stroke as seen in a Medieval swordfighting manual.

Regular maces, hammers, and other blunt weapons were equally effective if you could get a hard enough hit in without leaving yourself open, but they all suffered from part of the plate armor’s intelligent design. Nearly every part of it was smooth and/or rounded, meaning that it’s very easy for blows to ‘slide’ off, which wastes a lot of their power. This makes it very hard to get a ‘direct’ hit.

Here come the specialized weapons to save the day.

Above: A lucerne, or claw hammer. It’s just one of the specialized weapons, but it encompasses all their shared traits so I’m going to only list it.

These could be one-handed, two-handed, or long polearms, but the general idea was the same. Either crack bones beneath armor with the left part, or penetrate plate armor with the right part. The left part has four ‘prongs’ so that it can ‘grip’ smooth plate armor and keep its force when it hits without glancing off. On the right side it as a super sturdy ‘pick’, which is about the only thing that can penetrate the plate armor itself. On top it has a sharp tip that’s useful for fighting more lightly armored opponents.

3. Force them to the ground and stab them through the visor with a dagger.

This one is pretty self-explanatory. Many conflicts between two armored knights would turn into a wrestling match. Whoever could get the other on the ground had a huge advantage, and could finish his opponent, or force him to surrender, with a dagger.

By now you might be thinking “Dang, full plate armor has a lot of weaknesses, so how can it be called good armor?”

The answer is because, like all armor is supposed to do, it minimizes your target area. If armor is such that your enemy either needs to risk cutting their fingers to target extremely small weak points, bring a specialized weapons designed specifically for your armor, or wrestle you to the ground to defeat you, that’s some damn good armor. So yes, it will protect you pretty well.

Above: The red areas represent the weak points of a man not wearing armor.

Also, before I move on to Mobility, I’m going to talk briefly about a pet-peeve of mine: Boob-plates.

If you’re writing a fantasy book, movie, or video game, and you want it to be realistically themed, don’t give the women boob-shaped armor. It wasn’t done historically even in the few cases when women wore plate armor, and that’s because it isn’t as protective as a smooth, rounded breastplate like you see men wearing. A hit with any weapon between the two ‘boobs’ will hit with its full force rather than glancing off, and that’ll hurt. If you’re not going for a realistic feel, then do whatever you want. Just my advice.

Above: Joan of Arc, wearing properly protective armor.

An exception to this is in ancient times. Female gladiators sometimes wore boob-shaped armor because that was for entertainment and nobody cared if they lived or died. Same with male gladiators. There was also armor shaped like male chests in ancient times, but because men are more flat-chested than women, this caused less of a problem. Smooth, rounded breastplates are still superior, though.

3. Does it allow the wearer to keep his or her freedom of movement?

Okay, I’ve been writing this for like four hours, so thankfully this is the simplest question to answer. There’s a modern myth that plate armor weighed like 700 lbs, and that knights could barely move in it at all, but that isn’t true. On a suit of plate armor from the mid to late 1400s or early 1500s, all the joints are hinged in such a way that they don’t impede your movement very much at all.

The whole suit, including every individual plate, the chainmaille underneath the plates, the thick cloth or leather underneath the chainmaille, and your clothes and underwear all together usually weighed about 45-55 lbs, and because the weight was distributed evenly across your whole body, you’d hardly feel the weight at all. Much heavier suits of armor that did effectively ‘lock’ the wearer in place did exist, but they never saw battlefield use. Instead, they were for showing off at parades and for jousting. Jousting armor was always heavier, thicker, and more stiffly jointed than battlefield armor because the knight only needed to move certain parts of his body, plus being thrown off a horse by a lance–even a wooden one that’s not meant to kill–has a very, very high risk of injury.

Here’s a bunch of .gifs of a guy demonstrating that you can move pretty freely in plate armor.

Above: Can you move in it? Yes.

Here are links to the videos that I made these .gifs from:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vi757-7XD94

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NhWFQtzM4r0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hlIUrd7d1Q

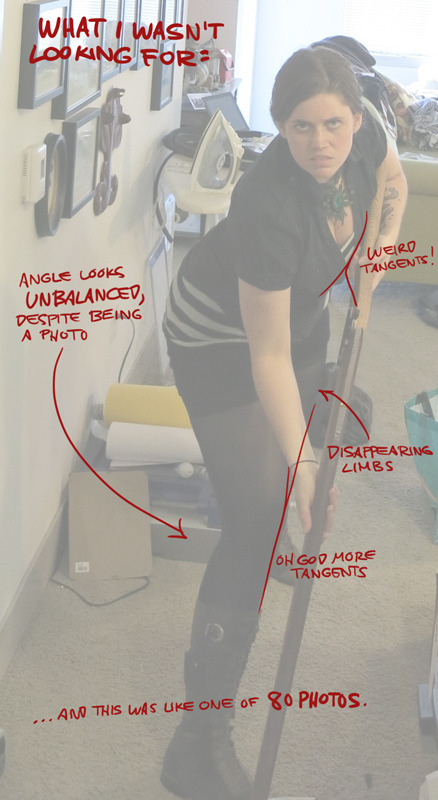

So I was chatting with the lovely Justin Oaksford yesterday, and he casually asked if I used photo reference for my recent Rolemodels piece- not as a bad thing, but because the pose and the camera angle read well. Pretty sure I grinned like an idiot when he brought it up because, goddammit, I’m proud that the work shows! I’ve felt like my work has been somewhat stilted as of late- I could feel myself subconsciously trending towards easier angles, easier poses, easier expressions just because it's slightly less frustrating for my brain to process- so getting that confirmation from a colleague was pretty damn satisfying.

I think there’s a tendency for artists to take pride in being able to draw out of your head, and, while that’s an admittedly important skill, what’s actually important is what that skill implies- it implies that you’ve internalized reference. That you’ve spent so much time looking at the world around you, studying it, drawing from it, breaking it down, that you’ve amassed an extensive mental library that you can draw from. You are Google reborn in the shallow husk of a human being.

But heck, the world’s a big place- what are the chances that you ever get to a point that you’ve internalized all of it? Internalized it AND ALSO are never going to forget it ever? Probably no chance at all. Sorry buddy. So rather than bemoaning the fact that we don’t have impenetrable search engine cyborg brains- yet- you sure as hell better still be using reference to fill in/refresh those empty shelves in your mental library. You shouldn’t have worm-ridden books about dinosaur anatomy from the 60’s in there. Stegosauruses with brains in their tails? CLEAN THAT SHIT OUT.

So my general process for using reference of any sort is:

loose thumbnails and brainstorming. If you have an idea, get that raw thing- unadulterated in it’s potential shittiness- onto paper. Good art is a combination of both instinct and discipline, so you don’t want to entirely discount those lightning strikes of brilliance. Or idiocy. Happens to all of us.

research and reference. Start gathering and internalizing whatever reference is pertinent to your piece- could be diagrams, art, photos, good old-fashioned READIN’, whathaveyou. Please note that this doesn’t mean find one picture of a giraffe- this means find tons of photos of giraffes, read about giraffes, understand giraffes, and learn how to incorporate that knowledge into your art with purpose and intent (Justin uses the word “intent” a lot so I’m stealing it). Don’t blindly copy what you see, but understand how to integrate it in an interesting and informed manner.

studies and practice. Could be lumped in with the previous step, granted, but it’s worth reiterating- if you’re drawing something new, it’s worth doing some studies. You discover things that you wouldn’t otherwise by just staring at them. It’s weird how I’m still learning this- “Gee golly, six-shooters are way easier to draw now that I’ve drawn a ton of them!” Yes wow Claire BRILLIANT. Gold star.

go for the gold. Finally, I’m sure it goes without saying, you integrate all of that research and knowledge into your initial thumbnails. If you learned something about anatomy, or fashion, or color, or butts, now you can drastically improve your original idea with this newfound knowledge. Also, per the images above, this is also your chance to improve on the reference- photos are a fantastic tool, but trust your instincts. Cameras can’t make informed decisions.

…So that’s my soapbox- it’s pretty easy, and it’s totally worth it. Research and reference lets you stand on the shoulders of giants- it lends legitimacy, specificity, and allure to your work that wouldn’t be there if you were just drawing out of your head 100% of the time. To put it simply- it makes your work ownable. It makes you stand out.

It makes you a better artist. :)

-C

-

tutoriarts reblogged this · 3 years ago

tutoriarts reblogged this · 3 years ago -

tomatesh reblogged this · 4 years ago

tomatesh reblogged this · 4 years ago -

colorwhale reblogged this · 4 years ago

colorwhale reblogged this · 4 years ago -

studying--beau liked this · 4 years ago

studying--beau liked this · 4 years ago -

fightopatholog1st liked this · 5 years ago

fightopatholog1st liked this · 5 years ago -

itstimetostudyforyourlife-blog liked this · 5 years ago

itstimetostudyforyourlife-blog liked this · 5 years ago -

studyingundersun reblogged this · 6 years ago

studyingundersun reblogged this · 6 years ago -

ameliasfolklore liked this · 6 years ago

ameliasfolklore liked this · 6 years ago -

foundintranselation reblogged this · 6 years ago

foundintranselation reblogged this · 6 years ago -

tulippvibess liked this · 6 years ago

tulippvibess liked this · 6 years ago -

dream-dancer4life reblogged this · 6 years ago

dream-dancer4life reblogged this · 6 years ago -

penguin-grl liked this · 6 years ago

penguin-grl liked this · 6 years ago -

constantstateofapathy liked this · 6 years ago

constantstateofapathy liked this · 6 years ago -

im---peachy reblogged this · 6 years ago

im---peachy reblogged this · 6 years ago -

im---peachy liked this · 6 years ago

im---peachy liked this · 6 years ago -

needsmuchpractice-blog liked this · 6 years ago

needsmuchpractice-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

futureboundd reblogged this · 6 years ago

futureboundd reblogged this · 6 years ago -

hypervy7 liked this · 6 years ago

hypervy7 liked this · 6 years ago -

lazilyclearprincess-blog1 liked this · 7 years ago

lazilyclearprincess-blog1 liked this · 7 years ago -

fleurglow liked this · 7 years ago

fleurglow liked this · 7 years ago -

bigbtslover-kookmin liked this · 7 years ago

bigbtslover-kookmin liked this · 7 years ago -

physicallytherapeutic liked this · 7 years ago

physicallytherapeutic liked this · 7 years ago -

shes--leaving-home liked this · 7 years ago

shes--leaving-home liked this · 7 years ago -

lifeinorder reblogged this · 7 years ago

lifeinorder reblogged this · 7 years ago -

yejiipink liked this · 7 years ago

yejiipink liked this · 7 years ago -

sorryitsnatasha liked this · 7 years ago

sorryitsnatasha liked this · 7 years ago -

a-wallflowers-blog liked this · 7 years ago

a-wallflowers-blog liked this · 7 years ago -

marichuu liked this · 7 years ago

marichuu liked this · 7 years ago -

wtrstudy-blog liked this · 7 years ago

wtrstudy-blog liked this · 7 years ago -

outofthedarkblog liked this · 7 years ago

outofthedarkblog liked this · 7 years ago -

bish-notes reblogged this · 7 years ago

bish-notes reblogged this · 7 years ago -

stutsu reblogged this · 7 years ago

stutsu reblogged this · 7 years ago -

idioticlantern reblogged this · 7 years ago

idioticlantern reblogged this · 7 years ago -

kleoe liked this · 7 years ago

kleoe liked this · 7 years ago -

dareyoutoleap liked this · 7 years ago

dareyoutoleap liked this · 7 years ago