Kris And Asriel But Dressed As Marlo And Yawzee From Super Smashing Fighters

Kris and Asriel but dressed as Marlo and Yawzee from Super Smashing Fighters

Don't Forget - Games aren't real!

More Posts from Redibanni and Others

How To Write A Compelling Character Arc

A character arc is a measure of how a character changes over time. These arcs are linear, which means they have a start and a conclusion. Character arcs are a significant aspect of any novel as they help clearly translate your character’s struggles and personal developments to your readers.

Unsure how to write a compelling character arc for your protagonist or other characters? Here are some tips to help you get started!

Pick A Type Of Arc

In order to create a compelling and successful character arc, you first need to recognise which type of arc is your character going to experience. Over the years people have developed various character arc types, however, there are three significant types every writer needs to be aware of when plotting their character’s story.

Positive Character Arcs

Positive character arcs are simply that—a character arc that results in a positive journey or development.

A majority of books and movies or other cinematic pieces feature positive character arcs. This is because everyone enjoys a happy ending. An ending that makes you feel fulfilled and excited for the protagonist’s journey, or brings tears to your waterline as you reminisce on how far they’ve come, and how much they deserve this positive ending.

A positive character arc doesn’t necessarily have to have a ‘’happily ever after’ however it needs to have a happy ending. If a character’s family was assassinated and at the end they get revenge on the antagonist who murdered their loved ones while developing themselves mentally, then that counts as a positive character arc.

When writing a positive character arc it’s important to keep a few things in mind, such as:

You need to end on a positive note. Things can be as chaotic as you want it to be, but you need to have a positive ending. Otherwise, you cannot define your character arc as positive.

Your protagonist needs to develop as a character. Whether that be mentally, emotionally, financially, etc.

Your protagonist cannot end up where they started. A character arc that ends in a full circle is more of a flat character arc than a positive one.

Negative Character Arcs

Just like a positive character arc, a negative one is very easy to explain. This is a character arc that is typically used when writing antagonists in the entertainment industry due to the negativity it brings. When writing a negative character arc for a protagonist you run the risk of making your readers feel unsatisfied or creating a ‘bad ending’.

Some examples of a negative character arc for a protagonist would be if the protagonist dies at the end of the book, or if the protagonists almost achieve their final goal but fail by a small shortcoming. Negative character arcs for a protagonist are usually implemented for the first few books of a series, especially in fantasy books.

Using a negative character for your antagonist is simple—they fail. The protagonist wins and the villain dies or gets locked up until their final moments.

When employing a negative character arc for a protagonist, here are some things to keep in mind:

They shouldn’t end up as a person similar to what they started off as. The point is to corrupt them, ruin them and turn them to the bad side. Perhaps even make them fall victim to the antagonists.

They can’t or will never achieve their long-term goal. Remember that goal you established at the start of your book? Your protagonist cannot achieve that. Or at least, they will never achieve it due to certain plot developments.

They lose someone or thing important to them. Negative character arcs for a protagonist are generally triggered due to the loss of someone or thing important to the protagonist. Maybe their mentor is murdered by the government, or their failure to achieve their goals makes them turn evil.

Flat Character Arcs

Flat character arcs are arcs that essentially lack any sort of arc. They are flat and begin and end with the character as the same type of person.

These arcs are generally used for side characters, but they can also be used for a protagonist. Think of characters like Sherlock Holmes, James Bond, etc. They go through several trials and tribulations, but even after it all their personality remains the same.

When writing a flat character arc it’s important to remember that your character cannot undergo any significant personality changes. Your protagonist can undergo such changes during the story, but they need to have a full circle by the end.

Divide Your Arc Into Short-Term Goals

Once you’ve decided where you want your character to end up at the end, you now need to know how they will get there. You can achieve this by referring to your long-term goal and then breaking them down into short-term goals.

The protagonist is supposed to find a hidden jewel at the end of the book and discovers how corrupt their government is. Alright, now break that down into short-term goals that will help your protagonist get to their end goal.

Group these goals and they will become stages for your book, break them down and you now have chapter outlines to work with.

Playing with the details of your character arcs can help you easily plan out your book’s plot and set a steady pace. You can also use this as a reference sheet when working on your WIP.

Take The World Outside Your Protagonist Into Perspective

Once you know the type of character arc you want and how you’re going to write it, it’s important to consider how this arc will impact your world. This includes your side characters as well as the general plot and layout of your world.

Character Arcs For Side Characters

It isn’t necessary to have a character arc for every single character, but it is almost impossible for only two characters to have an arc within hundreds of pages.

Whether it be your protagonist’s mentor or your antagonist’s assistant, it’s important to take their stories and personal development into consideration. How does the story’s plot impact their outlook on the world or their personality? Do any of the minor antagonists turn out to be morally grey? Does one of the smaller protagonists end up betraying the protagonist out of jealousy?

Remember, your smaller characters are also human. It’s important to take their stories and arcs into consideration so you can create a detailed and comprehensive world.

A great example of this could be anime characters. Most animes tend to have separate backstories and endings for every character. These backstories and endings don’t have to all be necessarily revealed to your readers, however, as an author you need to know where you’re going with each of your characters.

Reaction Arcs

One easy way to implement character arcs for your side characters is by using reaction arcs. I don’t know if this term has already been established, but I personally coined the term to refer to a character arc that is a direct reaction to another character’s arc.

Maybe your protagonist has a positive character arc and ends up becoming the most successful person in their field of work, but this results in a reaction arc for their best friend who turns bitter and has a negative character arc due to the way the protagonist’s story played out.

Reaction arcs differ from other arcs due to the fact that they cannot be achieved without establishing another character’s arc first. Following the above example, the best friend cannot become jealous and bitter until your protagonist’s character arc is established.

I hope this blog on how to write a compelling character arc will help you in your writing journey. Be sure to comment any tips of your own to help your fellow authors prosper, and follow my blog for new blog updates every Monday and Thursday.

Looking For More Writing Tips And Tricks?

Are you an author looking for writing tips and tricks to better your manuscript? Or do you want to learn about how to get a literary agent, get published and properly market your book? Consider checking out the rest of Haya’s book blog where I post writing and marketing tools for authors every Monday and Thursday.

Want to learn more about me and my writing journey? Visit my social media pages under the handle @hayatheauthor where I post content about my WIP The Traitor’s Throne and life as a teenage author.

Copyright © 2022 Haya Sameer, you are not allowed to repost, translate, recreate or redistribute my blog posts or content without prior permission

I want everyone’s best one liner writing advise!

Mine is that you have to know the ending of your story before you start it.

Tutorial - my cat wanted to share with you some tips and tricks. ———————————————– Originally from my Patreon, where there’s a little more to this. (Patrons get extra stuff and early releases)

Story Structures for your Next WIP

hello, hello. this post will be mostly for my notes. this is something I need in to be reminded of for my business, but it can also be very useful and beneficial for you guys as well.

everything in life has structure and storytelling is no different, so let’s dive right in :)

First off let’s just review what a story structure is :

a story is the backbone of the story, the skeleton if you will. It hold the entire story together.

the structure in which you choose your story will effectively determine how you create drama and depending on the structure you choose it should help you align your story and sequence it with the conflict, climax, and resolution.

1. Freytag's Pyramid

this first story structure i will be talking about was named after 19th century German novelist and playwright.

it is a five point structure that is based off classical Greek tragedies such as Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripedes.

Freytag's Pyramid structure consists of:

Introduction: the status quo has been established and an inciting incident occurs.

Rise or rising action: the protagonist will search and try to achieve their goal, heightening the stakes,

Climax: the protagonist can no longer go back, the point of no return if you will.

Return or fall: after the climax of the story, tension builds and the story inevitably heads towards...

Catastrophe: the main character has reached their lowest point and their greatest fears have come into fruition.

this structure is used less and less nowadays in modern storytelling mainly due to readers lack of appetite for tragic narratives.

2. The Hero's Journey

the hero's journey is a very well known and popular form of storytelling.

it is very popular in modern stories such as Star Wars, and movies in the MCU.

although the hero's journey was inspired by Joseph Campbell's concept, a Disney executive Christopher Vogler has created a simplified version:

The Ordinary World: The hero's everyday routine and life is established.

The Call of Adventure: the inciting incident.

Refusal of the Call: the hero / protagonist is hesitant or reluctant to take on the challenges.

Meeting the Mentor: the hero meets someone who will help them and prepare them for the dangers ahead.

Crossing the First Threshold: first steps out of the comfort zone are taken.

Tests, Allie, Enemies: new challenges occur, and maybe new friends or enemies.

Approach to the Inmost Cave: hero approaches goal.

The Ordeal: the hero faces their biggest challenge.

Reward (Seizing the Sword): the hero manages to get ahold of what they were after.

The Road Back: they realize that their goal was not the final hurdle, but may have actually caused a bigger problem than before.

Resurrection: a final challenge, testing them on everything they've learned.

Return with the Elixir: after succeeding they return to their old life.

the hero's journey can be applied to any genre of fiction.

3. Three Act Structure:

this structure splits the story into the 'beginning, middle and end' but with in-depth components for each act.

Act 1: Setup:

exposition: the status quo or the ordinary life is established.

inciting incident: an event sets the whole story into motion.

plot point one: the main character decided to take on the challenge head on and she crosses the threshold and the story is now progressing forward.

Act 2: Confrontation:

rising action: the stakes are clearer and the hero has started to become familiar with the new world and begins to encounter enemies, allies and tests.

midpoint: an event that derails the protagonists mission.

plot point two: the hero is tested and fails, and begins to doubt themselves.

Act 3: Resolution:

pre-climax: the hero must chose between acting or failing.

climax: they fights against the antagonist or danger one last time, but will they succeed?

Denouement: loose ends are tied up and the reader discovers the consequences of the climax, and return to ordinary life.

4. Dan Harmon's Story Circle

it surprised me to know the creator of Rick and Morty had their own variation of Campbell's hero's journey.

the benefit of Harmon's approach is that is focuses on the main character's arc.

it makes sense that he has such a successful structure, after all the show has multiple seasons, five or six seasons? i don't know not a fan of the show.

the character is in their comfort zone: also known as the status quo or ordinary life.

they want something: this is a longing and it can be brought forth by an inciting incident.

the character enters and unfamiliar situation: they must take action and do something new to pursue what they want.

adapt to it: of course there are challenges, there is struggle and begin to succeed.

they get what they want: often a false victory.

a heavy price is paid: a realization of what they wanted isn't what they needed.

back to the good old ways: they return to their familiar situation yet with a new truth.

having changed: was it for the better or worse?

i might actually make a operate post going more in depth about dan harmon's story circle.

5. Fichtean Curve:

the fichtean curve places the main character in a series of obstacles in order to achieve their goal.

this structure encourages writers to write a story packed with tension and mini-crises to keep the reader engaged.

The Rising Action

the story must start with an inciting indecent.

then a series of crisis arise.

there are often four crises.

2. The Climax:

3. Falling Action

this type of story telling structure goes very well with flash-back structured story as well as in theatre.

6. Save the Cat Beat Sheet:

this is another variation of a three act structure created by screenwriter Blake Snyder, and is praised widely by champion storytellers.

Structure for Save the Cat is as follows: (the numbers in the brackets are for the number of pages required, assuming you're writing a 110 page screenplay)

Opening Image [1]: The first shot of the film. If you’re starting a novel, this would be an opening paragraph or scene that sucks readers into the world of your story.

Set-up [1-10]. Establishing the ‘ordinary world’ of your protagonist. What does he want? What is he missing out on?

Theme Stated [5]. During the setup, hint at what your story is really about — the truth that your protagonist will discover by the end.

Catalyst [12]. The inciting incident!

Debate [12-25]. The hero refuses the call to adventure. He tries to avoid the conflict before they are forced into action.

Break into Two [25]. The protagonist makes an active choice and the journey begins in earnest.

B Story [30]. A subplot kicks in. Often romantic in nature, the protagonist’s subplot should serve to highlight the theme.

The Promise of the Premise [30-55]. Often called the ‘fun and games’ stage, this is usually a highly entertaining section where the writer delivers the goods. If you promised an exciting detective story, we’d see the detective in action. If you promised a goofy story of people falling in love, let’s go on some charmingly awkward dates.

Midpoint [55]. A plot twist occurs that ups the stakes and makes the hero’s goal harder to achieve — or makes them focus on a new, more important goal.

Bad Guys Close In [55-75]. The tension ratchets up. The hero’s obstacles become greater, his plan falls apart, and he is on the back foot.

All is Lost [75]. The hero hits rock bottom. He loses everything he’s gained so far, and things are looking bleak. The hero is overpowered by the villain; a mentor dies; our lovebirds have an argument and break up.

Dark Night of the Soul [75-85-ish]. Having just lost everything, the hero shambles around the city in a minor-key musical montage before discovering some “new information” that reveals exactly what he needs to do if he wants to take another crack at success. (This new information is often delivered through the B-Story)

Break into Three [85]. Armed with this new information, our protagonist decides to try once more!

Finale [85-110]. The hero confronts the antagonist or whatever the source of the primary conflict is. The truth that eluded him at the start of the story (established in step three and accentuated by the B Story) is now clear, allowing him to resolve their story.

Final Image [110]. A final moment or scene that crystallizes how the character has changed. It’s a reflection, in some way, of the opening image.

(all information regarding the save the cat beat sheet was copy and pasted directly from reedsy!)

7. Seven Point Story Structure:

this structure encourages writers to start with the at the end, with the resolution, and work their way back to the starting point.

this structure is about dramatic changes from beginning to end

The Hook. Draw readers in by explaining the protagonist’s current situation. Their state of being at the beginning of the novel should be in direct contrast to what it will be at the end of the novel.

Plot Point 1. Whether it’s a person, an idea, an inciting incident, or something else — there should be a "Call to Adventure" of sorts that sets the narrative and character development in motion.

Pinch Point 1. Things can’t be all sunshine and roses for your protagonist. Something should go wrong here that applies pressure to the main character, forcing them to step up and solve the problem.

Midpoint. A “Turning Point” wherein the main character changes from a passive force to an active force in the story. Whatever the narrative’s main conflict is, the protagonist decides to start meeting it head-on.

Pinch Point 2. The second pinch point involves another blow to the protagonist — things go even more awry than they did during the first pinch point. This might involve the passing of a mentor, the failure of a plan, the reveal of a traitor, etc.

Plot Point 2. After the calamity of Pinch Point 2, the protagonist learns that they’ve actually had the key to solving the conflict the whole time.

Resolution. The story’s primary conflict is resolved — and the character goes through the final bit of development necessary to transform them from who they were at the start of the novel.

(all information regarding the seven point story structure was copy and pasted directly from reedsy!)

i decided to fit all of them in one post instead of making it a two part post.

i hope you all enjoy this post and feel free to comment or reblog which structure you use the most, or if you have your own you prefer to use! please share with me!

if you find this useful feel free to reblog on instagram and tag me at perpetualstories

Follow my tumblr and instagram for more writing and grammar tips and more!

good traits gone bad

perfectionism - never being satisfied

honesty - coming off as rude and insensitive

devotion - can turn into obsession

generosity - being taken advantage of

loyalty - can make them blind for character faults in others

being dependable - always depending on them

ambitiousness - coming off as ruthless

optimism - not being realistic

diligence - not able to bend strict rules

protectiveness - being overprotective

cautiousness - never risking anything

being determined - too focussed on one thing

persuasiveness - coming off as manipulative

tidiness - can become an obsession

being realistic - being seen as pessimistic

assertiveness - coming off as bossy

pride - not accepting help from others

innocence - being seen as naive

selflessness - not thinking about themself enough

being forgiving - not holding others accountable

curiosity - asking too much questions

persistence - being seen as annoying

being charming - can seem manipulative

modesty - not reaching for more

confidence - coming off as arrogant

wit/humor - not taking things serious

patience - being left hanging

strategic - coming off as calculated

being caring - being overbearing

tolerance - being expected to tolerate a lot

eagerness - coming off as impatient

being observant - being seen as nosy

independence - not accepting help

being considerate - forgetting about themself

fearlessness - ignoring real danger

politeness - not telling what they really think

reliability - being taken advantage of

empathy - getting overwhelmed with feeling too much for other people

Some doodles as well!!

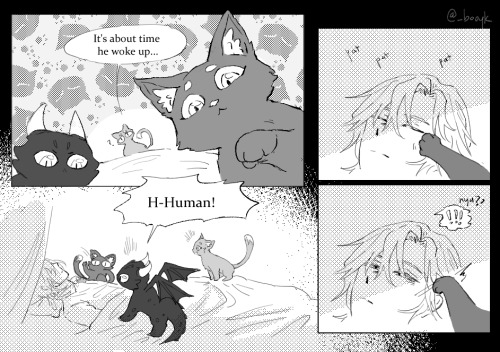

I was reading abralhugres ' "one last death" and "I'll save you when you're weak"

Storytelling in Any Season

Incorporating the seasons into my stories is enjoyable. Not only are seasons a relatable life experience, but passage of time can be tricky to portray without them. The best part about adding the seasons to a story is that they have strong potential to aid the plot.

Seasonal details that are easy to add to create the scene and affect the plot.

CLOTHING; if I walk this path in winter, I have to wear huge boots that can handle slick mud. If I walk it in summer, the dead grass scratches my bare legs because now I am wearing shorts.

EXTREME TEMPERATURE; whatever we do today it better be indoors and out of this heat wave/blizzard. If the battle/heist/romance/etc. takes place in this weather, there will be consequences!

CHARACTER MOOD; autumn is Character A's favorite time of year! they gain a positive, upbeat attitude as soon as they see signs of autumn. Character B feels dread and becomes easily agitated during autumn. The two of them clash more in autumn than any other season.

EVENTS; holidays aside, some seasons may be busier for one character than another. I had a weekend job during summers and was rarely available. Weddings are most common in spring. Community events that affect traffic, shops, or social atmosphere can occur at any time of year.

TRANSPORTATION; some parts of the world rely on different transport for different seasons. A bicycle when it is temperate, a bus or train when it is miserable. A car for dry weather is replaced with a car outfitted for inclement weather. A regular trip to the grocery store may even need to be cancelled completely. And don't forget air and water travel!

HISTORY/TRAUMA; certain seasons in your story may be marked by pain. This is the season the war took many lives. This is the month unforgettable tragedy occurred. The upcoming season marks the anniversary of a huge mistake we'd all like to forget. Social and personal customs will reflect this memorial.

FOOD; in the modern-day US we are used to most foods being available year-round. This is not the case globally or historically. Seasons can be marked by what foods are or aren't available. This can include meat, produce, and dairy, but it can also extend to dishes and meals.

RESOURCES; like food, weather and climate affect access to many things your characters may need. Washed out roads halt shipments, but heavy rain is good for crops. Intense heat can damage perishable supplies, but dries out firewood fast. Natural disasters halt production while simultaneously increasing demand. Even a weather event in another hemisphere can affect your character's resources.

Whenever you think "How do I portray the changing seasons?" pay attention to the changes you have to make each season. Places you go, your personal habits, the items you carry with you, the events you prepare for, and all of these real-life details affect YOUR "plot" every day. Consider which ones would affect your characters, and use them to both set the scene and move the story along.

---

✩ This was written in response/addition to @writingquestionsanswered post Incorporating Seasons Into a Story. Please see their post for other important tips!

+ If you enjoy my content and want to see more, consider sending a little thank you and Buy Me A Coffee!

+ Visit me on AO3 - Wattpad for my fanfiction, and Pinterest - Unsplash for photo inspiration.

How to write romantic tension

Here are some of my best tips to write a romantic build-up! (I believe all of these are inspired by a couple in my current project, oops!) Happy Valentine’s to everyone!

💜 Disagreements

Nothing shouts romantic tension better than when one of the characters is annoyed by the other’s habits or opinions. Usually this stems from a personal issue, or even form knowing they’re attracted to the other person!

If character A smokes, character B could be annoyed at them because they used to smoke themselves, but subconsciously the complaints are just an excuse to keep the conversation going.

💜 Arm’s length

Try to keep your characters at an arm’s length from each other, and experiment with the tension you can create at a distance. This will make any closer moments MUCH more impactful.

If character A is usually polite and respectful of personal space, but in an emotional moment they lean a tad too close, that strikes character B much harder.

💜 The turning point

What is the point where it becomes obvious to your characters that they like each other? You don’t have to immediately seal this in a kiss or a confession. Play with how this knowledge subtly changes their behaviour with one another.

Character A may get progressively flirtier or bolder when they realize character B is completely accepting of their advances. They may start to do “coupley things”, like hand-holding, or subtle comfort touches, without even having to talk about “where they’re at.”

Did you know I’ve got a Youtube channel? Watch my first few videos now! Subscribe through the [link here] or below!

-

originaldreamdream liked this · 2 months ago

originaldreamdream liked this · 2 months ago -

helloiammelra liked this · 6 months ago

helloiammelra liked this · 6 months ago -

theaartzu-blog liked this · 6 months ago

theaartzu-blog liked this · 6 months ago -

juiceposting liked this · 9 months ago

juiceposting liked this · 9 months ago -

mekofoxy liked this · 9 months ago

mekofoxy liked this · 9 months ago -

gobananas444 liked this · 9 months ago

gobananas444 liked this · 9 months ago -

4sunnyday4 liked this · 10 months ago

4sunnyday4 liked this · 10 months ago -

shurbrrt liked this · 1 year ago

shurbrrt liked this · 1 year ago -

femaleshinji liked this · 1 year ago

femaleshinji liked this · 1 year ago -

jilegogreengiantstories liked this · 1 year ago

jilegogreengiantstories liked this · 1 year ago -

marygargen liked this · 1 year ago

marygargen liked this · 1 year ago -

achuneddarchive liked this · 1 year ago

achuneddarchive liked this · 1 year ago -

toxicsweetcorn liked this · 1 year ago

toxicsweetcorn liked this · 1 year ago -

0fullofflaws liked this · 1 year ago

0fullofflaws liked this · 1 year ago -

trideltai liked this · 1 year ago

trideltai liked this · 1 year ago -

asatohikari liked this · 1 year ago

asatohikari liked this · 1 year ago -

bee-natural8 liked this · 1 year ago

bee-natural8 liked this · 1 year ago -

tre3kang liked this · 1 year ago

tre3kang liked this · 1 year ago -

bluebetweenworlds reblogged this · 1 year ago

bluebetweenworlds reblogged this · 1 year ago -

bluebetweenworlds liked this · 1 year ago

bluebetweenworlds liked this · 1 year ago -

aletelee liked this · 1 year ago

aletelee liked this · 1 year ago -

tea-and-bitchcuits liked this · 1 year ago

tea-and-bitchcuits liked this · 1 year ago -

ray-kel liked this · 1 year ago

ray-kel liked this · 1 year ago -

lunalycana liked this · 1 year ago

lunalycana liked this · 1 year ago -

pretendthisisaname reblogged this · 1 year ago

pretendthisisaname reblogged this · 1 year ago -

ghftsblog liked this · 1 year ago

ghftsblog liked this · 1 year ago -

the-shy-wolf liked this · 1 year ago

the-shy-wolf liked this · 1 year ago -

seirettes reblogged this · 1 year ago

seirettes reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mercurialdispositions liked this · 1 year ago

mercurialdispositions liked this · 1 year ago -

woxins liked this · 1 year ago

woxins liked this · 1 year ago -

seandh47 liked this · 1 year ago

seandh47 liked this · 1 year ago -

infizero reblogged this · 2 years ago

infizero reblogged this · 2 years ago -

infizero liked this · 2 years ago

infizero liked this · 2 years ago -

blazeofcourse liked this · 2 years ago

blazeofcourse liked this · 2 years ago -

galaxyofthewriter1213 liked this · 2 years ago

galaxyofthewriter1213 liked this · 2 years ago -

valkyrievampire liked this · 2 years ago

valkyrievampire liked this · 2 years ago -

eleganttrashfun liked this · 2 years ago

eleganttrashfun liked this · 2 years ago -

magcargoperson liked this · 2 years ago

magcargoperson liked this · 2 years ago -

acemapache reblogged this · 2 years ago

acemapache reblogged this · 2 years ago -

acemapache liked this · 2 years ago

acemapache liked this · 2 years ago -

strawberri26 liked this · 2 years ago

strawberri26 liked this · 2 years ago -

notbrucewayne48 liked this · 2 years ago

notbrucewayne48 liked this · 2 years ago -

charlotte-deshayes-wife liked this · 2 years ago

charlotte-deshayes-wife liked this · 2 years ago